Wichudapa/Shutterstock

Commercial aviation has become a cornerstone of our economy and society. It allows us to rapidly transport goods and people across the globe, facilitates over a third of all global trade by value, and supports 87.7 million jobs worldwide. However, the 80-tonne flying machines we see hurtling through our skies at near supersonic speeds also carry some serious environmental baggage.

My team’s recent review paper highlights some promising solutions the aviation industry could put in place now to reduce the harm flying does to our planet. Simply changing the routes we fly could hold the key to drastic reductions in climate impact.

Modern aeroplanes burn kerosene to generate the forward propulsion needed to overcome drag and produce lift. Kerosene is a fossil fuel with excellent energy density, providing lots of energy per kilogram burnt. But when it is burnt, harmful chemicals are released: mainly carbon dioxide (CO₂), nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), water vapour and particulate matter (tiny particles of soot, dirt and liquids).

Aviation is widely known for its carbon footprint, with the industry contributing 2.5% to the global CO₂ burden. While some may argue that this pales in comparison with other sectors, carbon is only responsible for a third of aviation’s full climate impact. Non-CO₂ emissions (mainly NOₓ and ice trails made from aircraft water vapour) make up the remaining two-thirds.

Taking all aircraft emissions into account, flying is responsible for around 5% of human-induced climate change. Given that 89% of the population has never flown, passenger demand is doubling every 20 years, and other sectors are decarbonising much faster, this number is predicted to skyrocket.

Daniel Ciucci/Unsplash

It’s not just carbon

Aircraft spend most of their time flying at cruise altitude (33,000 to 42,000 ft) where the air is thin, to minimise drag.

At these altitudes, aircraft NOₓ reacts with chemicals in the atmosphere to produce ozone and destroy methane, two very potent greenhouse gases. This aviation-induced ozone is not to be confused with the natural ozone layer, which occurs much higher up and protects the Earth from harmful UV rays. Unfortunately, aircraft NOₓ emissions cause more warming due to ozone production than they do cooling due to methane reduction. This leads to a net warming effect that makes up 16% of aviation’s total climate impact.

Also, when temperatures dip below -40℃ and the air is humid, aircraft water vapour condenses on particles in the exhaust and freezes. This forms an ice cloud known as a contrail. Contrails may be made of ice, but they warm the climate as they trap heat emitted from the Earth’s surface. Despite only lasting a few hours, contrails are responsible for 51% of the aviation industry’s climate warming. This means they warm the planet more than all aircraft carbon emissions that have accumulated since the dawn of powered flight.

Unlike carbon, non-CO₂ emissions cause warming through interactions with the surrounding air. Their climate impact changes depending on atmospheric conditions at the time and location of release.

Cutting non-CO₂ climate impact

Two of the most promising short-term options are climate-optimal routing and formation flight.

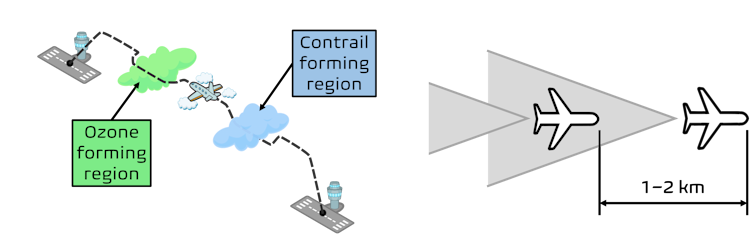

Climate-optimal routing involves re-routing aircraft to avoid regions of the atmosphere that are particularly climate-sensitive – for example, where particularly humid air causes long-lived and damaging contrails to form. Research shows that for a small increase in flight distance (usually no more than 1-2% of the journey), the net climate impact of a flight can be reduced by around 20%.

Flight operators can also reduce the impact of their aircraft by flying in formation, with one aircraft flying 1-2 km behind the other. The follower aircraft “surfs” the lead aircraft’s wake, leading to a 5% reduction in both CO₂ and other harmful emissions.

But flying in formation can reduce non-CO₂ warming too. When aircraft exhaust plumes overlap, the emissions within them accumulate. When NOₓ reaches a certain concentration, the rate of ozone production decreases and the warming effect slows.

And when contrails form, they grow by absorbing the surrounding water vapour. In formation flight, the aircraft’s contrails compete for water vapour, making them smaller. Summing all three reductions, formation flight could slash climate impact by up to 24%.

Decarbonising aviation will take time

The aviation industry has fixated on tackling carbon emissions. However, current plans for the industry to reach net zero by 2050 rely on an ambitious 3,000-4,000 times increase in sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) production, problematic carbon offsetting schemes, and the introduction of hydrogen- and electric-powered aircraft. All of these could take several decades to make a difference, so it’s crucial the industry cuts its environmental footprint in the meantime.

Climate-optimal routing and formation flight are two key examples of how we could make change happen faster, compared with a purely carbon-focused approach. But there is currently no political or financial incentive to change tack. It is time governments and the aviation industry start listening to the science, and take aircraft non-CO₂ emissions seriously.![]()

———————–

This blog is written by Cabot Institute for the Environment member Kieran Tait, PhD Candidate in Aerospace Engineering, University of Bristol. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

| Kieran Tait |