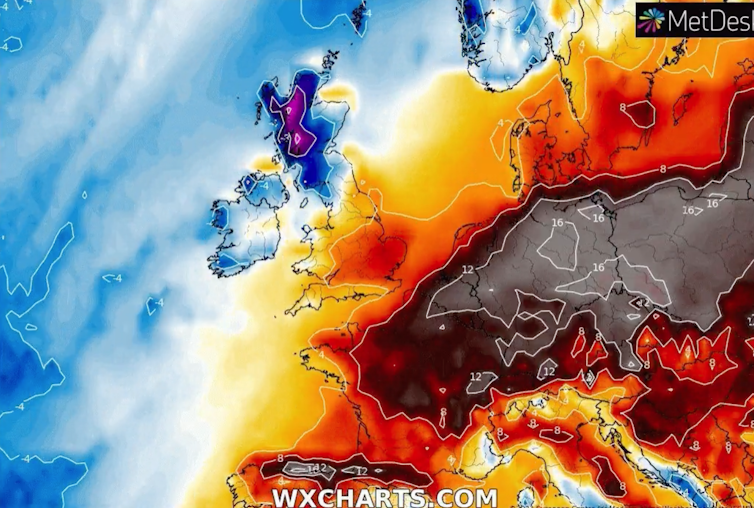

WX Charts, CC BY-NC

An extreme winter heatwave meant countries across Europe experienced a record-breaking New Year’s Day. New daily temperature records for the month of January were set in at least eight countries: Belarus, Czechia, Denmark, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Netherlands and Poland.

In many cases the temperatures were not just breaking the old highs, but smashing them by massive margins. On a typical January day in Warsaw, Poland, temperatures would barely go above freezing, yet the city recently experienced 19℃, breaking the previous January high by 5.1℃.

New January records were set at thousands of individual stations in many other countries such as 25.1℃ at Bilbao airport in Spain, 0.7℃ hotter than the previous record set only last year. Large areas of central and Eastern Europe experienced temperatures 10℃ to 15℃ warmer than average for this time of year – and that has persisted through the week.

When Europe experienced extreme heat in July of last year, more than 20,000 died. Fortunately winter heatwaves are much less deadly, but they can still affect both human society and natural ecosystems in many ways.

1. Less energy is needed

In Europe deaths due to cold weather vastly outweigh those caused by extreme high temperatures – in the UK there are ten times more. Warmer winters will reduce this excess mortality and, with the current cost-of-living crisis, many will have been relieved that a heatwave meant less energy was needed to heat their homes.

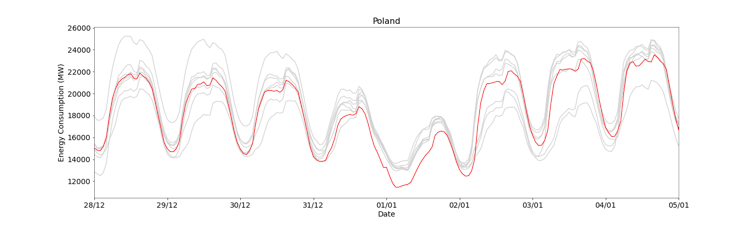

Electricity demand is influenced by things like the time of day, the day of the week and socio-economic factors like the COVID pandemic or the war in Ukraine. The weather also makes a difference. For example, in Poland and the Netherlands demand was noticeably lower than average, especially since January 1 was a Sunday. The extent of the heatwave also meant countries could refill some of their winter gas reserves, or large batteries.

Hannah Bloomfield / data: transparency.entsoe.eu, Author provided

2. Reduced yields for some crops

Winter warm spells don’t always have such a positive impact though. For instance a lack of snow in the mountains affects agriculture and can reduce crop yield, since snow creates an insulating blanket that prevents frost from penetrating into the soil. This means snow can actually increase soil moisture more than rainfall, thus improving growing conditions later in the season.

The big snow melt in spring time replenishes reservoirs and allows hydroelectricity generation, but unexpected snow melt can lead to flooding. Changes to the timings of these events will require preparation and adaptation to enable a steady supply of water to where we need it.

Warmer temperatures will create longer growing seasons in many regions. This is not always the case though. A recent study showed that for alpine grasslands an earlier growing season (the point when snow has melted entirely) leads to ageing and browning of the grasses in the later part of the summer.

3. The snow economy is in trouble

The heatwave caused ski resorts across the Alps to close in what should be their busiest time of year. In January the slopes would be expected to have a good covering of snow – but instead we saw green grassy fields.

This hits the local economy where many people rely on winter sports tourism. Events such as the Adelboden alpine ski World Cup are relying on artificial snow, which comes with a further environmental cost increasing the carbon footprint of ski resorts and requiring a large water supply. Indeed, the Beijing winter Olympics used the equivalent of daily drinking water for 900 million people to generate the artificial snow it required.

4. Animals out of sync with the climate

We humans are perhaps fortunate, as we are able to adapt. Some ski resorts have already opened mountain bike trails in winter to offer alternative tourism, but wildlife and ecosystems cannot adjust so rapidly.

In the mountains many species, such as ptarmigan and mountain hares, change their colouring for winter to camouflage in the white snow. The timing of this change is determined by length of day – not the temperature or amount of snow. These creatures are at greater risk of being preyed on when it is warmer.

Mark Medcalf / shutterstock

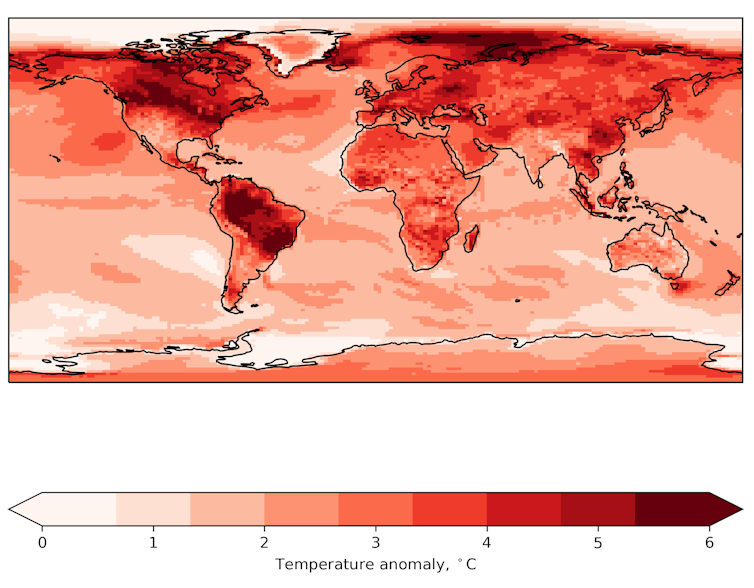

Over the past century heat extremes in Europe have increased in intensity and frequency. Both the general warming and heatwave events have been firmly attributed to humans.

Future projections suggest these trends will continue and heatwaves in both summer and winter will get hotter, last longer, and occur more often. We need to learn to adapt for these changes in all seasons and think about the impacts on everyone – and everything – on our planet.![]()

—————————-

This blog is written by Cabot Institute for the Environment members Dr Vikki Thompson, Senior Research Associate in Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol and Dr Hannah Bloomfield, Postdoctoral Researcher in Climate Risk Analytics, University of Bristol. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.