Bristol’s Research Development International (RDI) Team works with our academics and their partners across the globe to help them secure funding for research projects. We support applications to a wide range of external funding calls including those funded as part of the UK’s Aid budget and others focused on collaborations with global South partners.

We also run internal calls to help our researchers initiate, develop and sustain international partnerships. These schemes have sown the ground for partnerships to grow their projects and to successfully secure millions in funding.

A key aspect of our internal funding schemes is the need for projects to demonstrate that the partnership is equitable. This without doubt strengthens funding proposals and ensures outcomes meet the needs of the intended beneficiaries. We have also seen equitable partnerships become more of an expectation for external funders too, especially for calls that aim to tackle global challenges.

Equitable research partnerships that enable co-design and collaboration across sectors to combine diverse sources of knowledge are crucial for enabling transformative adaptation.

Tacking Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience Opportunities, UKRI 2022

Global challenges – our principles

The University of Bristol’s principles for global challenges research activity include our commitment to build equitable relationships. We fully support these statements of expectations:

- Partnerships should be transparent and based on mutual respect.

- Partnerships should aim to have clearly articulated equitable responsibilities, efforts, benefits and distribution of resources.

- Partnerships should recognise different inputs, different interests and different desired outcomes and should ensure the ethical sharing and use of data which is responsive to the identified needs of society.

Between 2017-2021 the University directly supported in excess of 120 global challenges projects with partners in over 55 countries located in the global South. These projects demonstrated the importance of investing time and resources into building equitable partnerships which are based on trust and understanding. The funding enabled researchers to gain and develop first-hand knowledge about how to develop inclusive partnerships where cultural differences are considered and understood. It also helped them to recognise that there are power dynamics within partnerships that are sometimes out of their control, for example the particular model of funding or Bristol’s own institutional processes. Others arise due to a lack of awareness of the local contexts in which overseas partners operate.

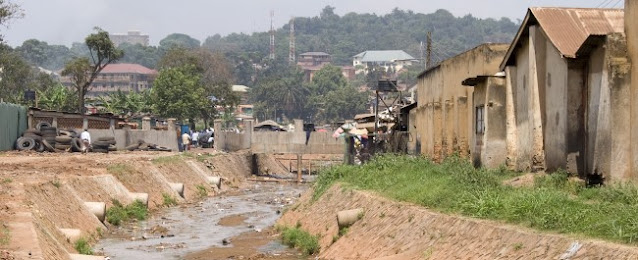

|

| A collaborative research project on mitigating everyday risks in Peru. Read more about this project. |

Developing international research collaborations

When we asked some of our award holders what advice they would give to researchers who would like to develop international global challenges research collaborations they commented:

“I think you have to go and visit and sit down and spend time talking, understanding perspectives, priorities, and local constraints. There are constraints that if you are based in the UK, you don’t even know are possible constraints, until you are there. People have got to like you, to feel you ‘hear’ them and are interested and understanding.”

“The basic element of overseas partnerships is to be respectful of your partners and recognise that they come with substantial technical expertise and understand their context far better than an overseas researcher will. It is crucial to listen to the partners and be willing to change you own ideas and plans in light of the inputs, insights and advice from the partners.”

“Communication was often difficult in the early stages of our partnership. If considering new partnerships again, I would ensure that we had more extensive discussions at the start about capacity, capability, and areas of particular interest so we maximise the likelihood that research designs match partner expectations”

“Recognise that the drivers for academics in other countries may not always be the same as those in the UK – your partners may care much more about community interaction or policy engagement than writing papers for instance.”

“Co-development and collaboration creates new possibilities in terms of outcomes and impact that are not possible alone – be patient and flexible with partners and processes that are needed to build these collaborations because the rewards can be significant.”

How to find international research partners

If you are interested developing an international research collaboration, your first question may be how do I find an international partner(s)? Some of our suggestions include:

- Seek advice from your School Research Director or Faculty International Director;

- Contact your research support colleagues who may be aware of existing projects working in a similar area and can put you in touch with your colleagues.

- Speak to your institutions research institutes and centres. These are often closely linked to institutions’ international engagement strategies and can enable interdisciplinary links within the institution that can lead to developing international collaborations.

- Like Bristol, your institution may be part of an existing international network, such as the Worldwide Universities Network (WUN). Contact the network’s team to find out what partnerships exist already and whether they can facilitate links with these institutions

- The South West International Development Network (SWIDN) is a cross-sector membership organisation of non-profit, academic institutions, businesses, consultants and individuals who are working in international development towards the SDGs. Your institution may have connections to similar organisations. If you are seeking partners for your research, they can share information with their NGO members.

What help does the RDI team provide to University of Bristol researchers and their international partners?

Our activities include discussing potential projects and how these fit with specific call requirements; how to complete applications, the information to be included and who in the University can provide additional support; how to generate impacts and policy; identifying potential future funding streams for sustaining partnerships; reviewing draft applications; assisting or signposting in respect of the associated administrative, financial and contractual requirements. We have also developed a toolkit to help Bristol researchers navigate all these aspects.

Hints and tips for global challenges research

Do

- take time to build your partnerships. Successful partnerships are built on trust and understanding. Look out for funding streams which will help you to meet them face to face.

- make sure the project is co-designed, it should be informed by the local contexts of the challenges(s) identified by partners and other stakeholders.

- consider the potential for mutual learning and knowledge exchange.

- recognise and understand that what you may think is a primary issue in a partner country, might not be a burning issue from your partner’s perspective.

- think about cultural differences and how you will need to accommodate or address these as the project develops.

- think about how time differences and different pressures may impact on how your project develops.

- be aware that funding deadlines are often very short for global challenges research and applications can take a considerable time to complete

- be aware that these funding streams are competitive.

Don’t

- try to shoehorn your research to meet the aims of a particular call. Funding panels can usually spot where this is the case.

- assume that professional services teams will be able to prioritise your application. Liaise with them at an early stage in your planning. Take time to become familiar with the University’s research costing systems and the associated procedures in place.

- assume that your University’s due diligence and contractual processes will always be straightforward and timely. These can be complex in some instances, especially where your partner(s).

Resources

- UKCDR – Equitable Partnerships Guide

- UKRI – Equitable partnerships

- Tomorrow’s Cities – Urban Risk in Transition. Defining and evaluating equitable partnerships: a rapid review

- Global Code of Conduct for research in resource-poor settings

Funding calls

Current UK funded international research development calls.

Recent equitable partnership projects

- Priorities for sustainable water services in Africa

- Making water and sanitation services more resilient to climate change

- Decentralised urban energy access

- Seismic risk knowledge exchange in East Africa

- Risks and resilience in the high mountains

- Mitigating everyday risks in Perú

- HIV, menopause and musculoskeletal health

———————————

This blog is written by Alison Tyers and Simon Glasser from the University of Bristol’s Research Development (International) team.