Jonathan Lenoir, Université de Picardie Jules Verne (UPJV) and Tommaso Jucker, University of Bristol

Forests are home to 80% of land-based biodiversity, but these arks of life are under threat. The rising average global temperature is forcing tiny plants like sidebells wintergreen on the forest floor (known as the understory) to shift upslope in search of cooler climes. Forest plants can’t keep up with the speed at which the climate is changing – they lag behind.

The pace at which forests adapt to changing conditions is so slow that species living in forest understories today are probably responding to more ancient changes in their environment. For instance, the Mormal Forest floor in northern France is, in several places, covered by a carpet of quaking sedge. This long grass-like plant betrays the former settlements of German soldiers who used it to make straw mattresses during the first world war.

Changes in how people managed the land, sometimes dating back to the Middle Ages or even earlier, leave a lasting fingerprint on the biodiversity of forest understories. Knowing how long the presence of a given species can carry on the memory of past human activities can tell scientists how long climate change is likely to have an influence.

Jonathan Lenoir, Author provided

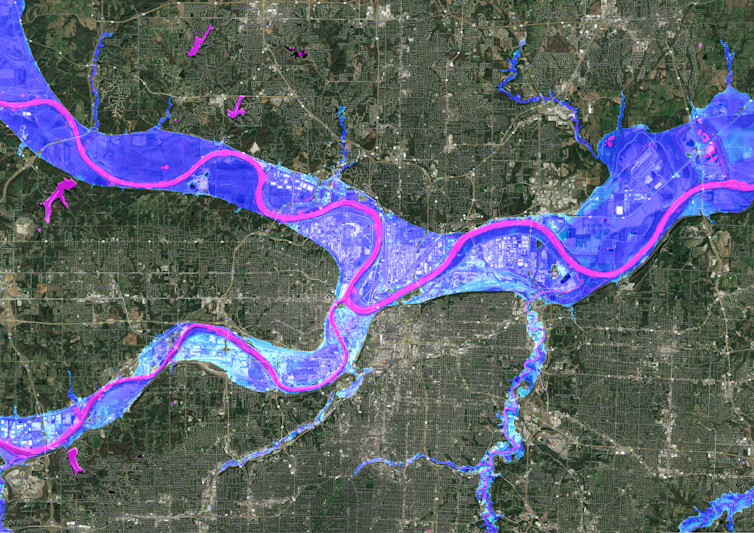

Ecologists are turning to technologies such as lidar to rewind the wheel of time. Lidar works on the same principles as radar and sonar, using millions of laser pulses to analyse echoes and generate detailed 3D reconstructions of the surrounding environment. This is what driverless cars use to sense and navigate the world. Since the late 1990s, lidar has enabled amazing discoveries, such as the imprints of Mayan civilisation preserved beneath the canopy of tropical forest.

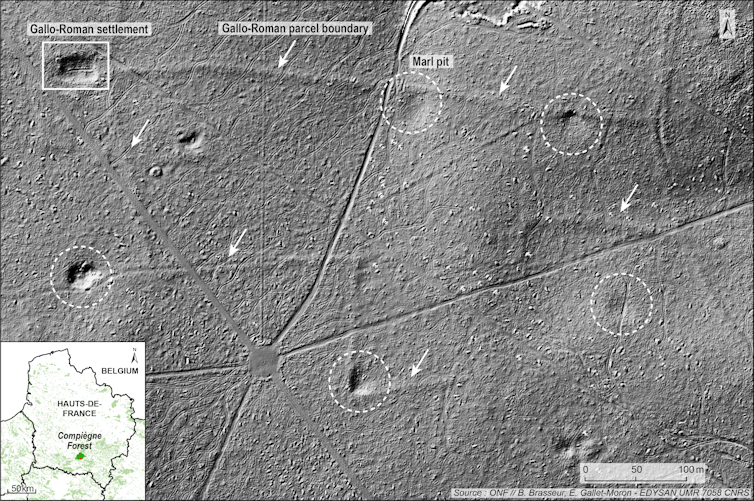

In a new paper, I, along with experts in ecology, history, archaeology and remote sensing, used lidar to trace human activity in the Compiègne Forest in northern France back to Roman times – much later than historical maps could ever do.

Illuminating ghosts from the past

Compared to farm fields, which are ceaselessly disturbed, forest floors tend to be well-preserved environments. As a result, the ground below the forest canopy may still bear the imprints of ancient human occupation.

Archaeologists know this pretty well and they increasingly rely on lidar technology as a prospecting tool. It allows them to virtually remove all the trees from aerial images and hunt artefacts hidden below treetops and fossilised under forest floors.

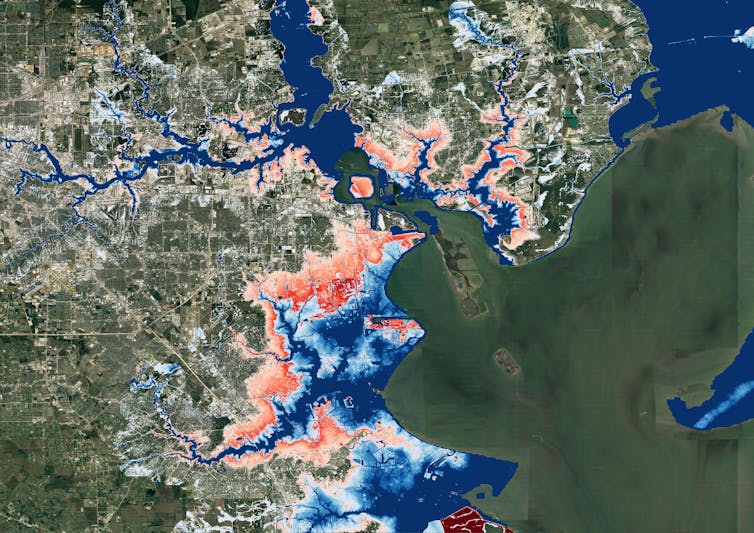

Using airborne lidar data acquired in 2014 over the Compiègne Forest in northern France, a team of archaeologists and historians found well-preserved Roman settlements, farm fields and roads. Long considered a remnant of prehistoric forest, the Compiègne was, in fact, a busy agricultural landscape 1,800 years ago.

Jonathan Lenoir, Author provided

A closer look at these ghostly images of the Compiègne Forest reveals several depressions within a fossilised network of Roman farm fields. Archaeologists excavated numerous depressions like this across many forests in north-eastern France and found that people from the late iron age and Roman era carved them.

These depressions were made to extract marls (lime-rich mud) to enrich farm fields in carbonate minerals for growing crops and to create local depressions where rainwater collects naturally for livestock to drink. Marling is still a widespread practice in crop production in northern France.

Jonathan Lenoir, Author provided

The long-lasting effects of human activity

These signs of Roman occupation in modern forests provide clues to why some plant species are present where we wouldn’t expect them to be.

On a summer day in 2007 in a corner of the Tronçais Forest in central France, a team of botanists found a little patch of nitrogen-loving species – blue bugle, woodland figwort and stinging nettle – nestled among more acid-loving plants.

Nothing special at first sight. Until archaeologists found that Roman farm buildings had once stood in that spot, with cattle manure probably enriching the soil in phosphorous and nitrogen.

Kateryna Pavliuk/Shutterstock

If a clutch of tiny plants can betray ancient farming practices dating back centuries or millennia, ongoing environmental changes, such as climate change, will have similarly long-lasting effects. Even if the Earth stopped heating, the biodiversity of its forests would continue changing in response to the warming signal, in a delayed manner, through the establishment of more and more warm-loving species for several centuries into the future.

Just as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has a mission to provide plausible scenarios on future climate change, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services aims to provide plausible scenarios on the fate of biodiversity. Yet none of the biodiversity models so far incorporate this lag effect. This means that model predictions are more prone to errors in forecasting the fate of biodiversity under future climate change.

Knowing about the past of modern forests can help decode their present state and model their future biodiversity. Now lidar technology is there to help ecologists travel back in time and explore the forest past. Improving the accuracy of predictions from biodiversity models by incorporating lagging dynamics is a big challenge, but it is a necessary endeavour for more effective conservation strategies.

——————————-

This blog is written by Jonathan Lenoir, Senior Researcher in Ecology & Biostatistics (CNRS), Université de Picardie Jules Verne (UPJV) and Cabot Institute for the Environment member Dr Tommaso Jucker, Research Fellow and Lecturer, School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.