Drones, also known as unmanned [sic] aerial vehicles (UAVs), are becoming an increasingly common technology within conservation, with uses ranging from mapping vegetation cover, to detecting poachers, to delineating community land claims. Drones are favoured as they’re cheaper and simpler than rival remote sensing technologies such as satellites, yet despite their benefits, they pose a number of issues regarding personal privacy rights and can be difficult to navigate in environments like dense forests. Moreover, as social scientists have previously highlighted, monitoring technologies such as drones have the potential to be used for covert surveillance in conservation areas as part of what they call ‘green securitisation’ (Kelly and Ybarra, 2016; Massé, 2018). To date, however, there has been limited discussion between drone practitioners and scientists across disciplines regarding what a drone can do, and how it is done.

This was the inspiration behind Drone Ecologies, an online workshop hosted by the University of Bristol on the 5th and 6th of July 2021. With over 60 participants representing various disciplines across the social and natural sciences, as well as experts from the arts, industry, and NGOs, the workshop aimed to create an open space for important interdisciplinary dialogues concerning the use of drones for conservation purposes. Through a series of panels, presentations, and breakout activities, we discussed the technical, operational, and analytical dimensions of drones, as well as the ethical, political, and sociocultural impacts of introducing drones and other monitoring technologies into conservation spaces. This essay offers an overview of the conversations that took place during the workshop, and we invite others to take part in these ongoing discussions.

|

| Image 1: Calibrating drone sensors. Credit: Isla Myers-Smith |

Our opening panel explored some of the operational benefits of drone technologies for environmental researchers. Drones can provide optical coverage over large areas with high spatial and temporal resolution, and have been successfully deployed to monitor various wildlife populations; assess changes in land cover; and map human-landscape interactions. However, with an increase in the technical capabilities of both drones and the sensors they carry, drones are becoming more than just airborne cameras. They can now be used to monitor other environmental components—e.g. noise, air pollution, and pollen levels—opening the door for new and diverse forms of data generation and analysis. Another emerging feature with huge potential for data collection is the integration of drones with other devices as part of the Internet of Things (IoT). Networks of coordinated drones that are able to share information and react in real-time could become instrumental in new anti-poaching efforts and for long-term, large-scale environmental monitoring.

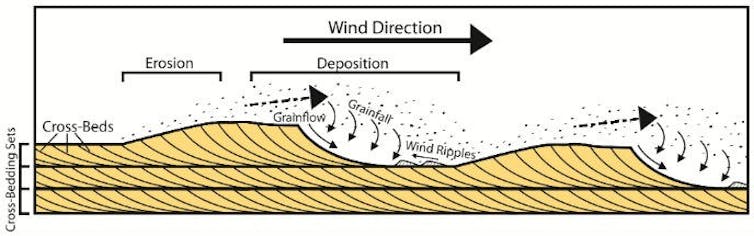

Alongside a discussion of the advantages that drones provide for researchers and state agencies, much attention was given to the ways in which drones may be used to benefit local communities by, for example, monitoring forest fires within their concessions, or by demonstrating sustainable forest stewardship. Speakers such as Jaime Paneque-Gálvez and Nicolás Vargas-Ramírez from the National Autonomous University of Mexico showed how several community-based projects in South and Central America successfully utilised low-cost drones for participatory mapping processes. The researchers presented their experiences in teaching peasant and Indigenous communities in Mexico, Bolivia and Peru how to pilot and maintain drones, and how to incorporate drone-based imagery and orthomosaics into GIS products. These high-resolution, geo-referenced maps could then be used as evidence for territorial claims, or to expose environmental damage to forests and rivers. The use of drones granted the communities access to greater levels of spatial and temporal resolution with lower financial barriers, as well as greater degrees of inclusivity and autonomy over data collection when compared to satellite products.

|

| Image 2: Composite imagery of illegal gold mining and participants of a community drone workshop in Peru. Credit: Paneque-Gálvez et al. (2017) |

Despite the logistical advantages of drones, there are still drawbacks regarding their use in environmental monitoring. Although they may reduce some environmental disturbances associated with monitoring—e.g. the cutting of tracks for transects—they also introduce new concerns, such as acoustic disturbance to wildlife under observation (and otherwise). However, some of the biggest concerns discussed during the second panel of the workshop were the negative impacts that drones may have on the communities living in and around the conservation areas being monitored. Trishant Simlai, a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge, gave a plenary presentation showing how drones in India, along with other technologies used for conservation monitoring, form part of a deliberate system of surveillance and harassment of forest communities by the forestry department, exacerbating local inequalities along lines of class, caste, and gender, and producing ‘atmospheres’ of control. The second panel’s presentations also highlighted how, regardless of the operator’s intent, communities and individuals alter their behaviour when monitoring technologies are deployed by, for instance, avoiding areas that may have previously provided refuge and privacy.

During a group dialogue on green securitisation, Boise State University’s Libby Lunstrum posited several key observations on drones which formed the basis of ongoing conversations. Firstly, the militaristic origin of drone technologies raises concerns about the complicity of drone use with broader shifts towards militarised conservation and human rights violations. Secondly, unlike the cases presented by Paneque-Gálvez and Vargas-Ramírez, underlying power relations may mean that drone technologies are not always truly accessible for all community members. There are also epistemic concerns regarding the relationship between the disembodied and ‘objective’ knowledge purportedly produced by drones and the embodied and situated forms of knowledges produced by other, on-the-ground methods. Finally, there are a range of critical questions concerning the political economy of drone production: who is investing in these technologies? How do militarised actors participate in conservation, at times greenwashing harmful practices against local communities? How are drones complicit with these dynamics, and how do we reconcile that with their positive uses?

Given the above considerations, and the increasing use of drones for data collection, much of the final discussion at the workshop focused on the ethical implications of using drones within conservation. Drawing inspiration from Sandbrook et al.’s (2021) recent paper on the socially responsible use of conservation monitoring technology, we amended the guidelines set out in their paper to be specifically applicable to drones. Some key concerns included issues of proportionality—whether drones are always necessary tools for conservation practices—and the importance of recognising and foreseeing the potential for social implications in the first place. These concerns, we believe, are often obscured by the techno-optimism that surrounds drones, alongside a generally prevalent faith in technological solutions to conservation problems.

|

| Image 3: Various groups involved in a community drone workshop in Panama. Credit: Paneque-Gálvez et al. (2017) |

By the end of the workshop, it was clear that the use of drones for conservation purposes is a complex matter, and their use is subject to many conflicting ideas. Drones configure power relations in which social, political, and economic asymmetries and vulnerabilities can be exacerbated. However, drones can also be used for environmental justice purposes and can aid in the reduction of inequalities when their use is democratised and appropriate for local communities. The workshop also revealed some of the networks, assemblages, and ecosystems that drones inhabit, and that constitute power relations in which drones could play a role. It is important that these networks of relationships and interests that mobilise drones and other complementary technologies—e.g. satellite images—are made explicit, so that we can understand new configurations of power that are developing and identify those who benefit from the introduction of drones.

Additionally, the workshop also highlighted the relevance of multi- and interdisciplinary dialogues in understanding and developing the use of drones and other types of monitoring technologies for conservation purposes. We believe that it is important for these interdisciplinary networks to be established, and to continue exploring the complex impacts that drones have on environments, humans, and conservation practices. The interdisciplinarity approach simultaneously engages different disciplinary approaches and ethics, mitigating any blind spots within research and fully illuminating any potential damage or disturbances arising from drone use. This workshop marked an opening of these dialogues which we hope will continue within this emerging space, building towards the development of cross-disciplinary guidelines and policies for the ethical and responsible use of drones in conservation.

Recorded sessions from the workshop can be viewed at http://www.bristol.ac.uk/cabot/events/2021/drone-ecologies.html

References

Kelly AB and Ybarra M (2016) Introduction to themed issue: ‘Green security in protected areas’. Geoforum 69: 171–175. DOI: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.09.013.

Massé F (2018) Topographies of security and the multiple spatialities of (conservation) power: Verticality, surveillance, and space-time compression in the bush. Political Geography 67: 56–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.10.001.

Paneque-Gálvez J, Vargas-Ramírez N, Napoletano B, et al. (2017) Grassroots innovation using drones for Indigenous mapping and monitoring. Land 6(4): 86. DOI: 10.3390/land6040086.

Sandbrook C, Clark D, Toivonen T, et al. (2021) Principles for the socially responsible use of conservation monitoring technology and data. Conservation Science and Practice 3(5). DOI: 10.1111/csp2.374.

——————————-

This blog was written by Cabot Institute for the Environment members Ben Newport and Georgios Tzoumas; and Mónica Amador and Juan Felipe Riaño. It has been reposted with kind permission. View the original blog.