Ink Drop/Shutterstock

The Paris Climate agreement represented a historic step towards a safer future for humanity on Earth when it was adopted in 2015. The agreement strove to keep global heating below 2℃ above pre-industrial levels with the aim of limiting the increase to 1.5℃ if possible. It was signed by 196 parties around the world, representing the overwhelming majority of humanity.

But in the intervening eight years, the Arctic region has experienced record-breaking temperatures, heatwaves have gripped many parts of Asia and Australia has faced unprecedented floods and wildfires. These events remind us of the dangers associated with climate breakdown. Our newly published research argues instead that humanity is only safe at 1℃ of global warming or below.

While one extreme event cannot be solely attributed to global heating, scientific studies have shown that such events are much more likely in a warmer world. Since the Paris agreement, our understanding of the impacts of global heating have also improved.

Jonathan Bamber, Author provided

Rising sea levels are an inevitable consequence of global warming. This is due to the combination of increased land ice melting and warmer oceans, which cause the volume of ocean water to increase. Recent research shows that in order to eliminate the human-induced component of sea-level rise, we need to return to temperatures last seen in the pre-industrial era (usually taken to be around 1850).

Perhaps more worrying are tipping points in the climate system that are effectively irreversible on human timescales if passed. Two of these tipping points relate to the melting of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets. Together, these sheets contain enough ice to raise the global sea level by more than ten metres.

The temperature threshold for these ice sheets is uncertain, but we know that it lies close to 1.5℃ of global heating above pre-industrial era levels. There’s even evidence that suggests the threshold may already have been passed in one part of west Antarctica.

Critical boundaries

A temperature change of 1.5℃ might sound quite small. But it’s worth noting that the rise of modern civilisation and the agricultural revolution some 12,000 years ago took place during a period of exceptionally stable temperatures.

Our food production, global infrastructure and ecosystem services (the goods and services provided by ecosystems to humans) are all intimately tied to that stable climate. For example, historical evidence shows that a period called the little ice age (1400-1850), when glaciers grew extensively in the northern hemisphere and frost fairs were held annually on the River Thames, was caused by a much smaller temperature change of only about 0.3℃.

Matty Symons/Shutterstock

A recent review of the current research in this area introduces a concept called “Earth system boundaries”, which defines various thresholds beyond which life on our planet would suffer substantial harm. To avoid passing multiple critical boundaries, the authors stress the need to limit temperature rise to 1℃ or less.

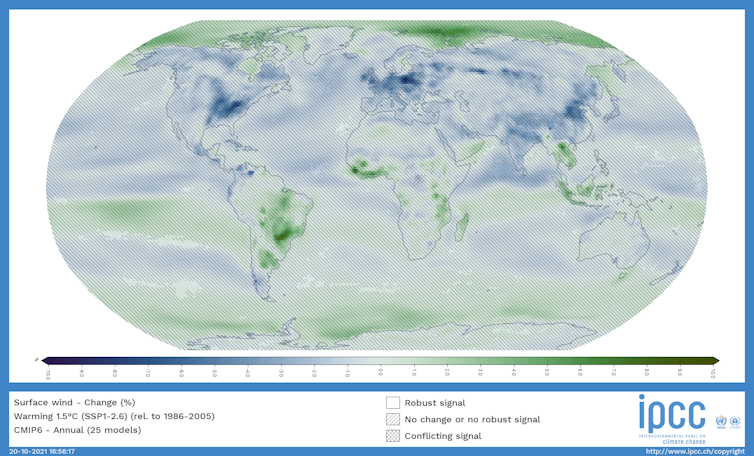

In our new research, we also argue that warming of more than 1℃ risks unsafe and harmful outcomes. This potentially includes sea level rise of multiple metres, more intense hurricanes and more frequent weather extremes.

More affordable renewable energy

Although we are already at 1.2℃ above pre-industrial temperatures, reducing global temperatures is not an impossible task. Our research presents a roadmap based on current technologies that can help us work towards achieving the 1℃ warming goal. We do not need to pull a technological “rabbit out of the hat”, but instead we need to invest and implement existing approaches, such as renewable energy, at scale.

Renewable energy sources have become increasingly affordable over time. Between 2010 and 2021, the cost of producing electricity from solar energy reduced by 88%, while wind power saw a reduction of 67% over the same period. The cost of power storage in batteries (for when the availability of wind and sunlight is low) has also decreased, by 70% between 2014 and 2020.

Captain Wang/Shutterstock

The cost disparity between renewable energy and alternative sources like nuclear and fossil fuels is now huge – there is a three to four-fold difference.

In addition to being affordable, renewable energy sources are abundantly available and could swiftly meet society’s energy demands. Massive capacity expansions are also currently underway across the globe, which will only further bolster the renewable energy sector. Global solar energy manufacturing capacity, for example, is expected to double in 2023 and 2024.

Removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

Low-cost renewable energy will enable our energy systems to transition away from fossil fuels. But it also provides the means of directly removing CO₂ from the atmosphere at a large scale.

CO₂ removal is crucial for keeping warming to 1℃ or less, even though it requires a significant amount of energy. According to research, achieving a safe climate would require dedicating between 5% and 10% of total power generation demand to effective CO₂ removal. This represents a realistic and attainable policy option.

Various measures are used to remove CO₂ from the atmosphere. These include nature-based solutions like reforestation, as well as direct air carbon capture and storage. Trees absorb CO₂ from the atmosphere through photosynthesis and then lock it up for centuries.

vinai chunkhajorn/Shutterstock

Direct air capture technology was originally developed in the 1960s for air purification on submarines and spacecrafts. But it has since been further adapted for use on land. When combined with underground storage methods, such as the process of converting CO₂ into stone, this technology provides a safe and permanent method of removing CO₂ from the atmosphere.

Our paper demonstrates that the tools and technology exist to achieve a safer, healthier and more prosperous future – and that it’s economically viable to do so. What appears to be lacking is the societal will and, as a consequence, the political conviction and commitment to achieve it.

————————-

This blog is written Cabot Institute for the Environment member Jonathan Bamber, Professor of Glaciology and Earth Observation, University of Bristol and Christian Breyer, Professor of Solar Economy, Lappeenranta University of Technology. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.