Through summer and early autumn 2021, Europe experienced a long period of dry conditions and low wind speeds. The beautifully bright and still weather may have been a welcome reason to hold off reaching for our winter coats, but the lack of wind can be a serious issue when we consider where our electricity might be coming from.

To meet climate mitigation targets, such as those to be discussed at the upcoming COP26 event in Glasgow, power systems are having to rapidly change from relying on fossil fuel generation to renewables such as wind, solar and hydropower. This change makes our energy systems increasingly sensitive to weather and climate variability and the possible effects of climate change.

That period of still weather badly affected wind generation. For instance, UK-based power company SSE stated that its renewable assets produced 32% less power than expected. Although this may appear initially alarming, given the UK government’s plans to become a world leader in wind energy, wind farm developers are aware these low wind “events” are possible, and understanding their impact has become a hot topic in energy-meteorology research.

A new type of extreme weather

So should we be worried about this period of low wind? In short, no. The key thing here is that we’re experiencing an extreme event. It may not be the traditional definition of extreme weather (like a large flood or a hurricane) but these periods, known in energy-meteorology as “wind-droughts”, are becoming critical to understand in order to operate power systems reliably.

Recent research I published with colleagues at the University of Reading highlighted the importance of accounting for the year-to-year variability in wind generation as we continue to invest in it, to make sure we are ready for these events when they do occur. Our team has also shown that periods of stagnant high atmospheric pressure over central Europe, which lead to prolonged low wind conditions, could become the most difficult for power systems in future.

Climate change could play a role

When we think about climate change we tend to focus much more on changes in temperature and rainfall than on possible variations in near-surface wind speed. But it is an important consideration in a power system that will rely more heavily on wind generation.

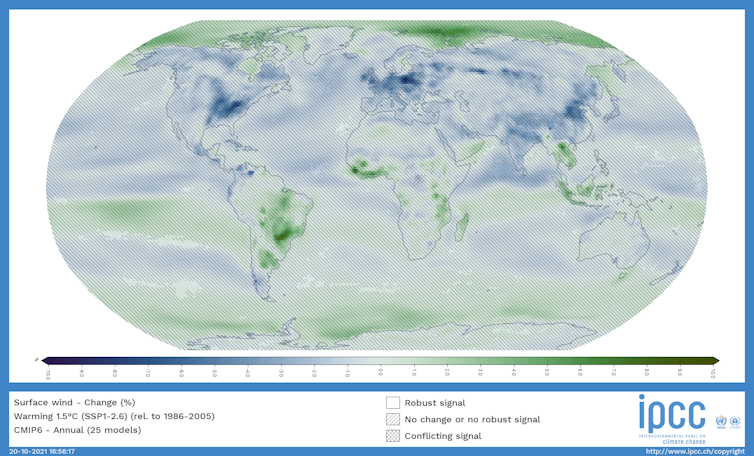

The latest IPCC report suggests that average wind speeds over Europe will reduce by 8%-10% as a result of climate change. It is important to note that wind speed projections are quite uncertain in climate models compared with those for near-surface temperatures, and it is common for different model simulations to show quite contrasting behaviour.

Colleagues and I recently analysed how wind speeds over Europe would change according to six different climate models. Some showed wind speeds increasing as temperatures warm, and others showed decreases. Understanding this in more detail is an ongoing topic of scientific research. It is important to remember that small changes in wind speed could lead to larger changes in power generation, as the power output by a turbine is related to the cube of the wind speed (a cubic number is a number multiplied by itself three times. They increase very fast: 1, 8, 27, 64 and so on).

IPCC Interactive Atlas, CC BY-SA

The reductions in near-surface wind speeds seen in the above map could be due to a phenomenon called “global stilling”. This can be explained by the cold Arctic warming at a faster rate than equatorial regions, which means there is less difference in temperature between hot and cold areas. This temperature difference is what drives large-scale winds around the globe through a phenomenon called thermal wind balance.

With all the talk of wind power being the answer to our energy needs, amid spiralling gas prices and the countdown to COP26, the recent wind drought is a clear reminder of how variable this form of generation can be and that it cannot be the sole investment for a reliable future energy grid. Combining wind with other renewable resources such as solar, hydropower and the ability to smartly manage our electricity demand will be critical at times like this summer when the wind is not blowing.![]()

——————————

This blog was written the Cabot Institute for the Environment member Dr Hannah Bloomfield, Postdoctoral Researcher in Climate Risk Analytics, University of Bristol. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read all blogs in our COP26 blog series: