|

| “Green Jobs not Job Cuts” by John Englart (Takver) is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 |

A couple of weeks ago I attended the “Skilling Up for the Clean Energy Transition: Creating a Net Zero Workforce” IPPR discussion. Given that we had 1.5 hours to get input from 5 presenters and about 20 participants, it was not really possible to put many thoughts across. Hence, this blog. Using some of the questions set out at the IPPR discussion, I started to put together some answers based on our work from the EnergyREV Skills work group (so far). Seeing that there is quite a lot to say, I will focus here on only 3 questions set out at the IPPR meeting:

Question 1: What are the main challenges and opportunities we face in the transition to net-zero?

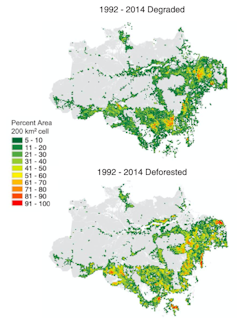

Today an average person on Earth consumes 1.5 planets [1]. In other words, we need 1.5 planets worth of forests, seas, land, and other resources to produce what an average person consumes and be able to absorb the emissions and negative impacts of it. And this number varies between developing and developed countries (e.g., 1.1 for China and 4.1 for USA).

For the UK we will be looking at 2.5 planets per person! Transitioning to net-zero economy then implies drastic change to our everyday production and consumption structures, processes, and habits.

Such change cannot be accomplished by one stakeholder, by few regulatory changes, or legislations. A systemic change in the mindset of the whole country is needed: from school education, to university level training, from industrial and societal regulations and legislation, to societal values that drive the kinds of companies that entrepreneurs want to run, and jobs that employees want to take, to the way that products and services are valued and consumed.

In considering this transition, we take a look at the energy sector, asking: how can we transition to renewables-based, local energy systems? Let us first clarify:

Why renewables-based? Because that is the only clean, continuously available energy source.

Why local? Because renewables are locally distributed and so should be harnessed where they are located. Moreover, wherever possible, the generated energy should be consumed where it is produced to avoid transmission losses as well as extensive costs of transmission infrastructures.

1.1 So what are the challenges in transitioning to renewables-based local energy systems?

1.1.1 Political landscape

The most recent Global Talent Index Report (GETI) [2] based on 17,000 respondents from 162 countries has shown that, although there is an obvious skills shortage, the most worrying issue for the renewable energy sector is, in fact, the political landscape. A lack of subsidies is of huge concern to the renewable industry, significantly more so than to the conventional and better established non-renewable sectors. Similarly, stability of the policies is a key determinant for investment into the new technologies and renewables sector.

1.1.2 Transitional mindset

Provisioning the right political landscape requires a transitional mindset within the society. Such a mindset would enable people to support the policies even though many of these would threaten to uproot their normal daily lives. This social support is essential not only for accepting the (potentially unpopular) policies, but also for taking an active role in the required change of daily practices (e.g., engaging with Demand-Response services, installation of own renewable generation and storage equipment, etc.) both as a consumer, and as a professional choosing to seek employment within the zero-emissions sector. This (I think) is the biggest challenge of all, as it requires A change of mindset and lifestyle of the whole of the country’s population. All of this cannot be achieved without:

- widespread ecological education: Such education should be provisioned to all of the citizens: from children to retired.

- commitment of resources to enable and support the necessary changes: it will not be enough to explain to families that driving a car is harmful for the planet; the family should get access to an alternative viable transportation option, so that they are able to get to school and work on time. To give a few examples (for UK):

- the transportation service would need to be improved (if it takes me 1 hour to walk to my work place and 1 hour if I take the bus, what is the point of the bus?);

- work practices would have to be changed to support flexible start/end as well as working from home/alternative locations to reduce the need for peak-time transportation pressure;

- change in hiring practices for jobs that require physical presence, would have to account for the workers’ ability to reach their workplace in carbon-neutral way;

- change would be needed in pricing/taxation of products, ensuring that the cost of carbon is taken into consideration (a move which, if not prepared for carefully, will undoubtedly be met with a lot of resistance from both producers and consumers)

Without such education and resource commitments the policies to aid decarbonisation are likely to create disruption and unrest, as recently seen with the ‘gilets jaunes’ in France. When president, E. Macron proposed a rise in tax on diesel and petrol without any transitional arrangements or subsidies for the alternative cleaner, electric vehicles, protesters took to the streets in violent clashes with the police [4].

1.1.3 Skills Shortage

Skills gap (or shortage) is a disequilibrium between the skills available from workers and those demanded of them by employers.

The skills shortage is a looming crisis that many in the renewable energy sector are also worried about: in accordance with GETI [2], 60% of respondents believe there is only 5 years to act before it hits. So what talent is lacking?

- The discipline of Engineering was reported to be in highest need, 50% of which were mechanical and electrical/E&I engineers – both 25% – followed by R&D at 20% and project leadership following with 25%;

- Lack of understanding of the system as a whole: how multiple energy generation methods can work together and complement each other;

- Legal experts and policy makers in steering the path to change;

- Implementation of effective and relevant training and education programmes;

- Vision of how all of these factors come together.

Such a gap can cause structural unemployment whereby the unemployed workers lack the skills needed to get the jobs. The shocks in economic activity that can lead to structural unemployment in the area of low-carbon and localised energy systems can arise from three main drivers:

- Firstly, as industries become more energy efficient and less polluting, the demand for occupations (such as drilling engineers) decreases whereas there is an increase in the demand for others, such as solar panel technicians. In some cases the occupations are relatively transferable. For example, an individual working on oil or gas drilling sites will be able to transition to the geo-thermal industry which relies on similar methods for heat extraction. The change in market behaviour can also be encouraged by consumer habits, for instance, through mass demand for greener energy which in turn causes the industry to adapt in order to meet the demands of their customer base.

- Secondly, entirely new occupations can emerge as a result of developments in technology. Occupations are also limited by this factor since a technology may not be available in a certain country or relocation to an area where the occupation is vacant may not be a feasible option.

- Thirdly, the introduction of regulation and environmental policy can force the industry to alter its structure. For example, policies may be put in place that ban certain materials or processes with negative environmental impacts [3].

The key risks to the sector, as a result of skills shortages, include decreased efficiency, loss of business and reduced productivity. These consequences will trigger a negative feedback loop since it is likely that there will be less incentive to work in the given industry if it is seen as a failing one.

How could the skills shortage be addressed?

The required skilled workers can be:

- Attracted from other industries with transferable skills (e.g., increasing need for the geo-thermal energy drill operators can be filled by attracting such operators from the shrinking oil and gas industry)

- Provisioning training: however, the length of a training course may cause long lead times and it is also necessary to incentivise individuals into enrolling in the training programmes in the first place.

- One way to speed up this process is for companies to offer apprenticeships and teach workers the skills or training ‘on-the-job’.

- Another option is to establish partnerships between employers and educational institutions, providing timely input on the expected types of training and shortages expected ahead of time, allowing for the training to be provisioned ahead.

- Clearer career progression, with demonstrated career pathways and specialisation opportunities.

- Increased remuneration and benefits packages, motivating the individuals to invest into (re-)training.

Improved societal image of clean jobs: As shown in the recent Talent Index Report [2] , remuneration was one of the least common reasons for the young people choosing to work in the renewables sector. A possible explanation could be that for the 25-34 year olds the concern for the climate is more apparent. Hence, they may enter the sector as they wish to take action against global warming rather than for gaining “job perks”. Thus satisfaction from work that contributes to the social good could become a major motivator in its own right.

Question 2: What is the role of government, employers and trade unions in securing a skills system fit for a decarbonised future?

Our recent review of the factors that affect skills shortages [8] revealed a picture presented in Figure 1 below. Here the factors most frequently noted as affecting skills shortages are:

- policy and regulation (e.g., feed-in tariff which increased demand for solar installers);

- technology (such as automation);

- change in markets due to competitiveness;

- education (e.g., education may be of a low standard or not up-to-date); and

- mass changes in consumption habits (which can shift demand away from certain goods and services and towards others, which in turn increases the demand at many stages of the value chain).

Factors mentioned which are noted as of mid-range impact are:

- physical changes in the environment as we are seeing with the climate crisis;

- number of training providers which may also reflect a regional shortage;

- job incentives such as wages or location;

- demographics, i.e., in localities where younger generations relocate or where women have lower levels of participation;

- funding towards skills and training or R&D;

- social awareness for the benefit of low-carbon alternatives;

- structural change;

- labour market information whereby individuals do not know which skills they need;

- the number of graduates in the necessary area (or generally) may be low; and

- business model changes which cause disturbances on company-level.

|

| Figure 1: Factors affecting skill shortages (source [8]). |

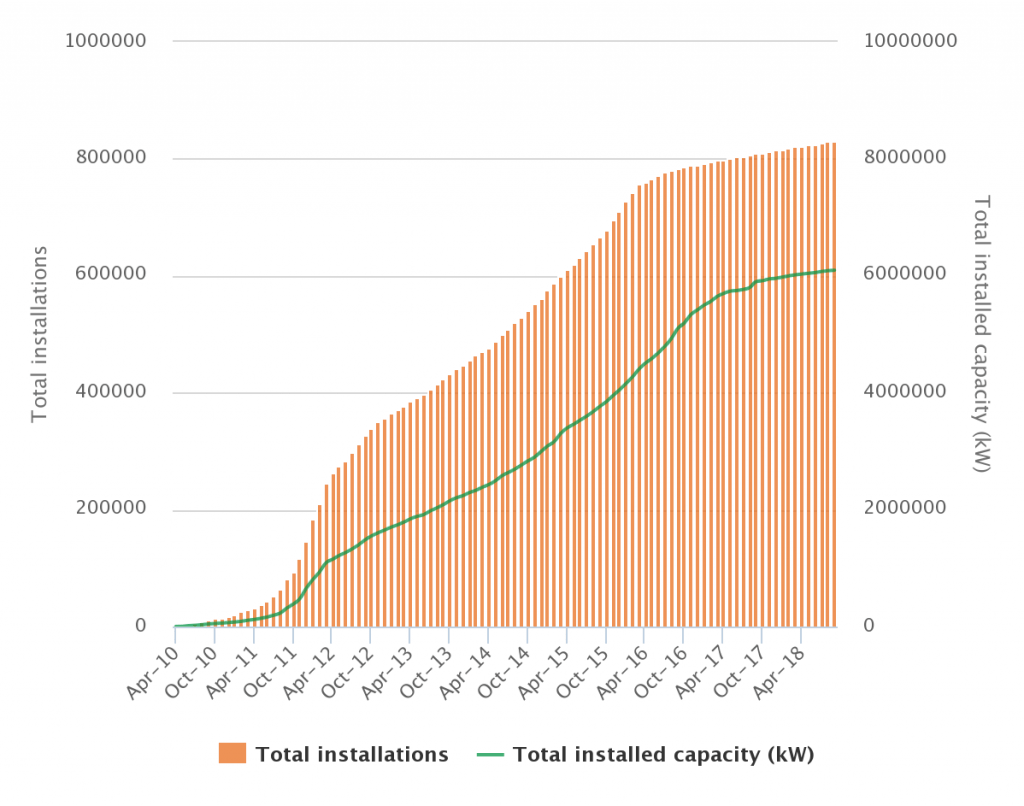

2.1 Government

From bans on harmful products to the introduction of a carbon tax, the government has an extraordinarily influential power in promoting a smooth transition to low carbon and more localised energy systems through legislative prohibitions as well as by providing both incentives and disincentives. This is clearly shown in Figure 2 that illustrates the success of encouraging installations of solar panels through the introduction of the Feed-in Tariff in 2010. The growth in the number of installations post April 2016 could partly reflect the rush to set up projects before further reductions in subsidies take effect. Nonetheless, this example of a positive incentive for participation in cleaner production methods should be learnt from to support the transition.

|

| Figure 2: Quarterly breakdown of number of installations and total installed capacity accredited under the Feed-in Tariff. Figure obtained from [5] |

The tools that the government has at its disposal include:

- Policy and regulation:

- Ban on harmful industrial practices and products (including unpriced carbon emissions);

- Carbon taxation;

- Technology regulation (e.g., clear regulation on use of blockchain, acceptance of peer-to-peer energy trading, regulation of self-generation and storage, all of which will drive investment into specific technologies and enable business models);

- Change in markets due to competitiveness by taxation, e.g., taxing fossil fuel-based vehicles to cross-subsidise the electric ones, allow continuous supplier switching for energy consumption, etc.;

- Change the value system in economics: move away from economic growth and GDP as progress indicators to Happiness Index, Job Satisfaction, Clean Environment and alike. This will change the business models that companies use;

- Price-based impact on consumption habits, e.g., price is cost of carbon in meat and diary products.

- Education:

- Public education for mindset transition through media and information which affects social awareness for the benefit of low-carbon alternatives, as well as ensure up-to date content provision;

- Change the value system in education: school and educational curriculum review to introduce the values of environmental protection, social and personal sustainability, and provide inspirational examples of successful life not as for those who become “rich and famous” but of those who contribute to environment and society. This will both affect social awareness for the benefit of low-carbon alternatives and support change in consumption habits as well as encourage younger employees and women to get engaged with the low-carbon sector.

- Investment:

- Support transition with investment into infrastructure support (provide funding towards skills and training or R&D);

- Provide re-training opportunities (through funding towards skills and training or R&D);

- Invest into areas with high energy potential (e.g., off-shore wind, wave and tidal to get the locations attractive for families, and so workers, affecting the demographic factors).

2.2 Industry Leaders:

The tools that the industry has at its disposal are:

- Lead by example: e.g., in renewable energy the leaders who can encourage the mindset transition are the large corporations such as Google, Apple and Facebook who are all in a race to operate on 100% renewable energy in their worldwide facilities [6] . This action is committing to investment in training and R&D, as well as technology adoption and fostering increased social awareness.

- On-the-job training: education programmes at workplace to help to provide an adequately skilled workforce within their companies and in the wider industry. This directly relates to workers’ education and investment into skills and R&D.

- Communication and collaboration with educational institutions and government to warn about the expected skills shortages and help train skilled employees ahead, which promotes better education and training, as well as provides clear information about the labour market to the students in schools and universities.

- Adopt innovative business models driven by new technology and new values (e.g., social enterprises, environmentally-focused businesses, etc.).

- Develop standards across industry: provide clear professional progression routes and job incentives, e.g., current lack of installers for heat pumps leads to plumbers with boiler installation experience being recruited for these jobs, yet these plumbers have to continue boiler maintenance to retain plumber licences.

2.3 Trade Unions:

The tools that the trade unions have at their disposal are:

- Support career transitions:

- Work with the management of the energy systems organisations to set transition targets and provide training for workers in transitioning to the new energy systems;

- Work with the universities and other training organisations to develop training provision for workers in transitioning to the new energy systems;

- Support quality assurance:

- Lobby to accept standards and certification for new energy jobs (like heat pump installers);

- De-risk hiring in new professions by ensuring employers are meeting their minimum obligations;

- Hold Industry accountable:

- by integrating the zero-carbon targets into the set of legal obligations for which the unions monitor breaches.

2.4 Others:

It should be noted that other stakeholders are also very influential, though are not discussed here due to space and time constraints. To name a few such stakeholders:

- Individuals

- Communities

- Local Communities

- Religious Groups

- Youth Groups

- Lobby Groups

- Activists, etc

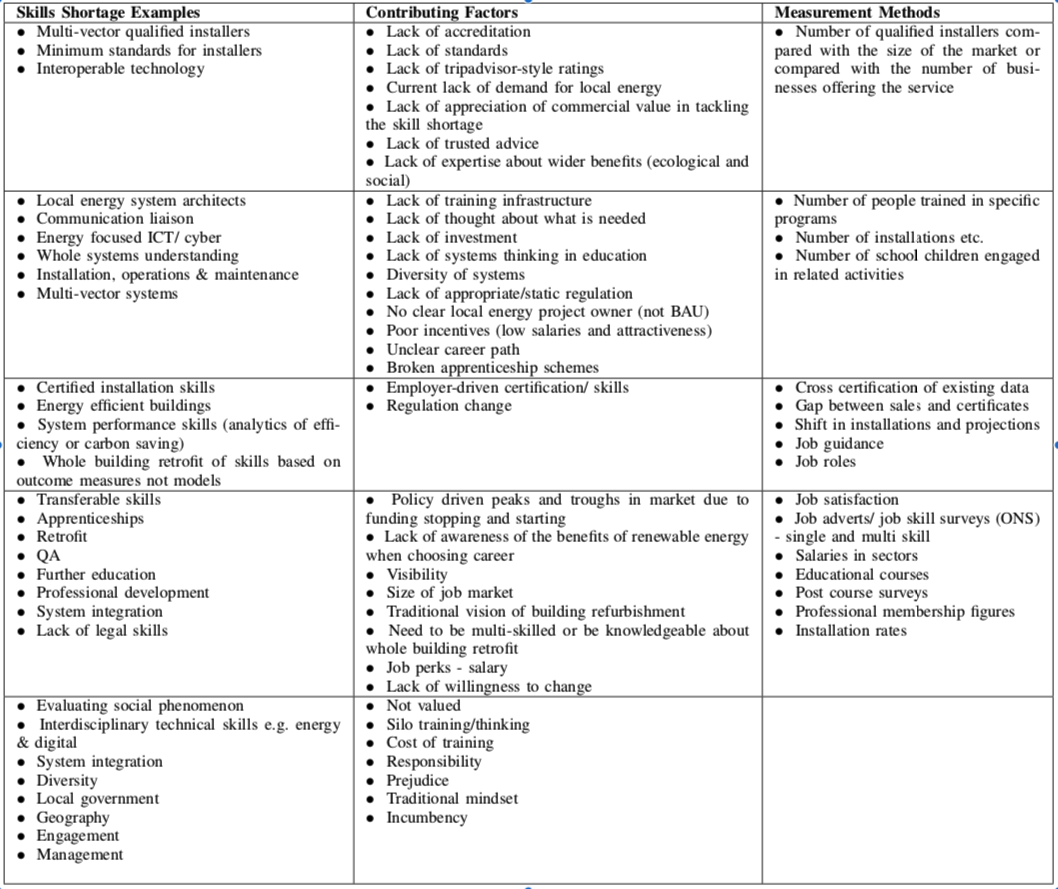

Question 3: What are the improvements that can be made to the skills system to overcome these challenges?

In a recent study [7] we invited 34 researchers and practitioners from across the UK’s energy systems to discuss the current state of the skills gap with regards to the localised renewables-based energy systems in the UK. The participants talked about various examples of the current skills shortages, their causes and ways to observe and measure them. The results of the said study are presented in Table 1 below.

|

| Table 1: Skills Shortages: Examples, Contributing Factors & Metrics (source [7]) |

Question 2 above already discusses what some key stakeholders can and should do to address the factors (as noted in Figure 1) underpinng skills shortages. There is no need to repeat all that has been note in response to Question 2, but only to highlight that the factors listed in Table 1 directly link up with the broader categories of factors noted in Figure 1. Thus, many of the factors noted in this table can also be addressed through tools discussed in Question 2.

Additionally, having carried out a mapping of stakeholders within the local energy systems [9], we identified the below 35 (non exhaustive) categories, all of which must be consulted when working towards a viable zero-carbon energy system provision. Thus, a solution that takes a whole systems perspective is unavoidable!

List of Stakeholder Categories to be considered in transition to clean energy systems (note, this is a non-exhaustive list):

- Building retrofitting

- Energy storage

- Transmission and Distribution

- Transport – EVs

- Transport – public

- Heating – heat pumps + geo-thermal

- Heating – solar thermal

- Heating – heat networks

- Heating – CHP

- Cooling – refrigeration

- Cooling – CCHP

- Biomass – waste to power

- Biomass – waste to heat

- Waste heat to power

- Wind energy

- Solar PV

- Marine energy

- Hydropower

- Hydrogen fuel and fuel cells

- Community energy

- Power plants

- Oil & gas

- Materials and components

- Financial services

- Reclamation, Reuse & Recycling (+ Waste management)

- Energy Efficiency

- Data Analytics & IoT

- Environmental Protection Groups

- Policy/Legal services

- Demand-side services

- Societal engagement & user behaviour

- Local government

- Government initiatives/departments

- Academia

- Non-academic training

References

[1] Tim de Chant, data from Global Footprint Network. URL: https://www.footprintnetwork.org

[2] Airswift and Energy Jobline, “The Global Energy Talent Index Report 2019,” 2019.

[3] O. Striestska-Ilina, C. Hofmann, D. H. Mercedes, and J. Shinyoung, “Skills for Green Jobs: A Global View: Synthesis Report Based on 21 Country Studies,” International Labour Organization, 2011.

[4] A. France-Presse, “Extinction rebellion goes global in run-up to week of international civil disobedience,” The Guardian, 2018. [On- line]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/dec/30/paris-police-fire-tear-gas-yellow-vest-gilet-jaunes-protesters

[5] Ofgem, “FIT quarterly breakdown,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/environmental-programmes/fit/contacts-guidance-and-resources/public-reports-and-data-fit/feed-tariffs-quarterly-statistics#thumbchart-c4831688853446394-n91793

[6] A. Moodie, “Google, apple, facebook towards 100% renewable energy target,” The Guardian, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable- business/2016/dec/06/google-renewable-energy-target-solar-wind-power

[7] Yael Zekaria, Ruzanna Chitchyan: Exploring Future Skills Shortage in the Transition to Localised and Low-Carbon Energy Systems. ICT4S 2019. URL: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2382/ICT4S2019_paper_34.pdf

[8] “Literature Review of Skill Shortage Assessment Models”, EnergyREV Project Report. Yael Zekaria, Ruzanna Chitchyan, Sept. 2019.

[9] “Report on Stakeholder Groups”, Yael Zekaria, Ruzanna Chitchyan, 9 July 2019

————————————–

This blog is written by Cabot Institute member Dr Ruzanna Chitchyan, at the University of Bristol. Ruzanna is a senior lecturer in Software Engineering and an EPSRC fellow on Living with Environmental Change. She works on software and requirements engineering for sustainability.

|