“This is a long shot!”

These were the words used by Richard Jones (Science Fellow, Met Office) in August 2021 when he asked if I would consider leading a NERC proposal for a rapid six-month collaborative international research and scoping project, aligned to the COP26 Adaptation and Resilience theme. The deadline was incredibly tight but the opportunity was too good to pass up – we set to work!

Background to Lusaka and FRACTAL

Zambia’s capital city, Lusaka, is one of Africa’s fastest growing cities, with around 100,000 people in the early 1960s to more than 3 million people today. 70% of residents live in informal settlements and some areas are highly prone to flooding due to the low topography and highly permeable limestone sitting on impermeable bedrock, which gets easily saturated. When coupled with poor drainage and ineffective waste management, heavy rainfall events during the wet season (November to March) can lead to severe localised flooding impacting communities and creating serious health risks, such as cholera outbreaks. Evidence from climate change studies shows that heavy rainfall events are, in general, projected to increase in intensity over the coming decades (IPCC AR6, Libanda and Ngonga 2018). Addressing flood resilience in Lusaka is therefore a priority for communities and city authorities, and it became the focus of our proposal.

Lusaka was a focal city in the Future Resilience for African CiTies and Lands (FRACTAL) project funded jointly by NERC and DFID from 2015 to 2021. Led by the Climate System Analysis Group (CSAG) at the University of Cape Town, FRACTAL helped to improve scientific knowledge about regional climate in southern Africa and advance innovative engagement processes amongst researchers, practitioners, decision-makers and communities, to enhance the resilience of southern African cities in a changing climate. I was lucky enough to contribute to FRACTAL, exploring new approaches to climate data analysis (Daron et al., 2019) and climate risk communication (Jack et al., 2020), as well as taking part in engagements in Maputo, Mozambique – another focal city. At the end of FRACTAL there was a strong desire amongst partners to sustain relationships and continue collaborative research.

I joined the University of Bristol in April 2021 with a joint position through the Met Office Academic Partnership (MOAP). Motivated by the potential to grow my network, work across disciplines, and engage with experts at Bristol in climate impacts and risk research, I was excited about the opportunities ahead. So when Richard alerted me to the NERC call, it felt like an amazing opportunity to continue the work of FRACTAL and bring colleagues at the University of Bristol into the “FRACTAL family” – an affectionate term we use for the research team, which really has become a family from many years of working together.

Advancing understanding of flood risk through participatory processes

Working closely with colleagues at Bristol, University of Zambia, University of Cape Town, Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI – Oxford), Red Cross Climate Centre, and the Met Office, we honed a concept building on an idea from Chris Jack at CSAG to take a “deep dive” into the issues of flooding in Lusaka – an issue only partly explored in FRACTAL. Having already established effective relationships amongst those involved, and with high levels of trust and buy-in from key institutions in Lusaka (e.g., Lusaka City Council, Lusaka Water Security Initiative – LuWSI), it was far easier to work together and co-design the project; indeed the project conceived wouldn’t have been possible if starting from scratch. Our aim was to advance understanding of flood risk and solutions from different perspectives, and co-explore climate resilient development pathways that address the complex issue of flood risk in Lusaka, particularly in George and Kanyama compounds (informal settlements). The proposal centred on the use of participatory processes that enable different communities (researchers, local residents, city decision makers) to share and interrogate different types of knowledge, from scientific model datasets to lived experiences of flooding in vulnerable communities.

The proposal was well received and the FRACTAL-PLUS project started in October 2021, shortly before COP26; PLUS conveys how the project built upon FRACTAL but also stands for “Participatory climate information distillation for urban flood resilience in LUSaka”. The central concept of climate information distillation refers to the process of extracting meaning from multiple sources of information, through careful and open consideration of the assumptions, strengths and limitations in constructing the information.

The “Learning Lab” approach

Following an initial evidence gathering and dialogue phase at the end of 2021, we conducted two collaborative “Learning Labs” held in Lusaka in January and March 2022. Due to Covid-19, the first Learning Lab was held as a hybrid event on 26-27 January 2022. It was facilitated by the University of Zambia team with 20 in-person attendees including city stakeholders, the local project team and Richard Jones who was able to travel at short notice. The remainder of the project team joined via Zoom. Using interactive exercises, games (a great way to promote trust and exchange of ideas), presentations, and discussions on key challenges, the Lab helped unite participants to work together. I was amazed at the way participants threw themselves into the activities with such enthusiasm – in my experience, this kind of thing never happens when first engaging with people from different institutions and backgrounds. Yet because trust and relationships were already established, there was no apparent barrier to the engagement and dialogue. The Lab helped to further articulate the complexities of addressing flood risks in the city, and showed that past efforts – including expensive infrastructure investments – had done little to reduce the risks faced by many residents.

One of the highlights of the Labs, and the project overall, was the involvement of cartoon artist Bethuel Mangena, who developed a number of cartoons to support the process and extract meaning (in effect, distilling) the complicated and sensitive issues being discussed. The cartoon below was used to illustrate the purpose of the Lab, as a meeting place for ideas and conversations drawing on different sources of information (e.g., climate data, city plans and policies) and experiences of people from flood-affected communities. All of the cartoons generated in the project, including the feature image for this blog, are available in a Flickr cartoon gallery – well worth a look!

Image: Cartoon highlighting role of Learning Labs in FRACTAL-PLUS by Bethuel Mangena

Integrating scientific and experiential knowledge of flood risk

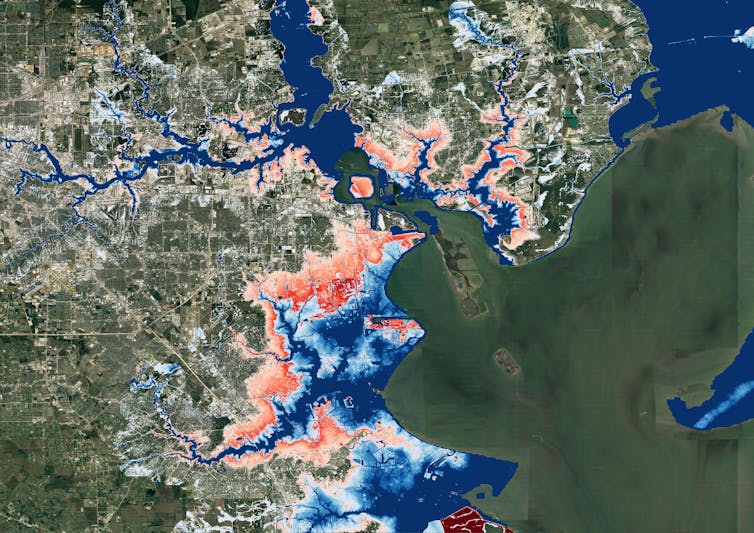

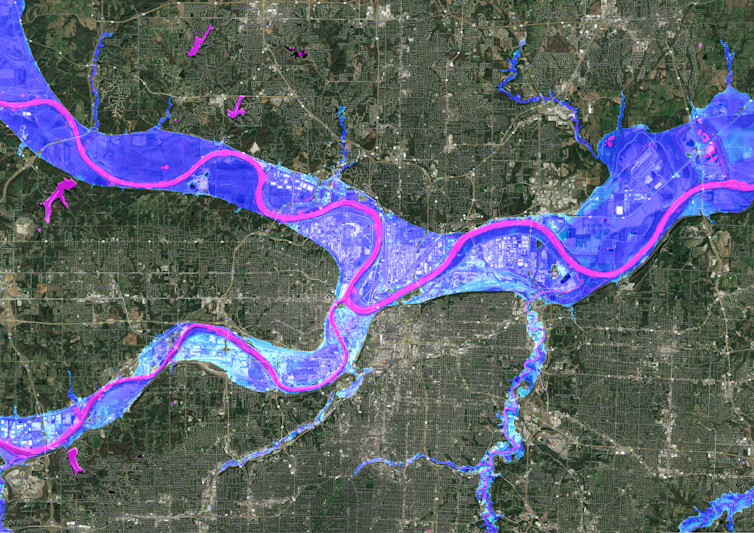

In addition to the Labs, desk-based work was completed to support the aims of the project. This included work by colleagues in Geographical Sciences at Bristol, Tom O’Shea and Jeff Neal, to generate high-resolution flood maps for Lusaka based on historic rainfall information and for future climate scenarios. In addition, Mary Zhang, now at the University of Oxford but in the School of Policy Studies at Bristol during the project, collaborated with colleagues at SEI-Oxford and the University of Zambia to design and conduct online and in-person surveys and interviews to elicit the lived experiences of flooding from residents in George and Kanyama, as well as experiences of those managing flood risks in the city authorities. This work resulted in new information and knowledge, such as the relative perceived roles of climate change and flood management approaches in the levels of risk faced, that was further interrogated in the second Learning Lab.

Thanks to a reduction in covid risk, the second lab was able to take place entirely in person. Sadly I was unable to travel to Lusaka for the Lab, but the decision to remove the virtual element and focus on in-person interactions helped further promote active engagement amongst city decision-makers, researchers and other participants, and ultimately better achieve the goals of the Lab. Indeed the project helped us learn the limits of hybrid events. Whilst I remain a big advocate for remote technology, the project showed it can be far more productive to have solely in-person events where everyone is truly present.

The second Lab took place at the end of March 2022. In addition to Lusaka participants and members of the project team, we were also joined by the Mayor of Lusaka, Ms. Chilando Chitangala. As well as demonstrating how trusted and respected our partners in Lusaka are, the attendance of the mayor showed the commitment of the city government to addressing climate risks in Lusaka. We were extremely grateful for her time engaging in the discussions and sharing her perspectives.

During the lab the team focused on interrogating all of the evidence available, including the new understanding gained through the project from surveys, interviews, climate and flood data analysis, towards collaboratively mapping climate resilient development pathways for the city. The richness and openness in the discussions allowed progress to be made, though it remains clear that addressing flood risk in informal settlements in Lusaka is an incredibly challenging endeavour.

Photo: Participants at March 2022 Learning Lab in Lusaka

What did we achieve?

The main outcomes from the project include:

- Enabling co-exploration of knowledge and information to guide city officials (including the mayor – see quote below) in developing Lusaka’s new integrated development plan.

- Demonstrating that flooding will be an ongoing issue even if current drainage plans are implemented, with projections of more intense rainfall over the 21st century pointing to the need for more holistic, long-term and potentially radical solutions.

- A plan to integrate flood modelling outputs into the Lusaka Water Security Initiative (LuWSI) digital flood atlas for Lusaka.

- Sustaining relationships between FRACTAL partners and building new links with researchers at Bristol to enable future collaborations, including input to a new proposal in development for a multi-year follow-on to FRACTAL.

- A range of outputs, including contributing to a FRACTAL “principles” paper (McClure et al., 2022) supporting future participatory projects.

It has been such a privilege to lead the FRACTAL-PLUS project. I’m extremely grateful to the FRACTAL family for trusting me to lead the project, and for the input from colleagues at Bristol – Jeff Neal, Tom O’Shea, Rachel James, Mary Zhang, and especially Lauren Brown who expertly managed the project and guided me throughout.

I really hope I can visit Lusaka in the future. The city has a special place in my heart, even if I have only been there via Zoom!

“FRACTAL-PLUS has done well to zero in on the issue of urban floods and how climate change pressures are making it worse. The people of Lusaka have continually experienced floods in various parts of the city. While the problem is widespread, the most affected people remain to be those in informal settlements such as George and Kanyama where climate change challenges interact with poor infrastructure, poor quality housing and poorly managed solid waste.” Mayor Ms. Chilando Chitangala, 29 March 2022

————————————————————————————-

This blog is written by Dr Joe Daron, Senior Research Fellow, Faculty of Science, University of Bristol;

Science Manager, International Climate Services, Met Office; and Cabot Institute for the Environment member.