Elites are often rightly blamed for resisting bold action needed to tackle climate change. But what if elite alliances are more fragile than commonly assumed? What if we consider Elite Incumbent Resistance – to transitions in food, energy and finance – not as a homogenous bloc of resistance towards sustainability transitions, but instead as made up of temporary, fragile alliances held together in ways that might be amenable to disruption?

A group of interdisciplinary researchers brought together by the British Academy’s Virtual Sandpit on Just Transition, set out to explore this question by piloting a new approach to studying the COP26 Climate Summit.

Starting Points

This thought experiment emerged from a critique of existing International Political Economy literature on climate negotiations which tends to focus on intense resistance to transitions to sustainable societies from elite groups benefiting from the status quo. This approach tends to homogenise incumbent elite-alliances, making them appear more robust than they really are. We were curious about what would happen if we instead focused on the vulnerabilities inherent in any alliances and how they are maintained and undone in climate negotiations.

As tools to help us think this through, we firstly turned to Laclau and Mouffe’s work on hegemony and socialist strategy. This is an old text but still relevant as it shows how all alliances are built on what they call relations of ‘equivalence’, which means, in simple terms, coming to a compromise about what key words (‘sustainable growth’ anyone?) mean. These equivalences, however, are always temporary and can, in theory, be unsettled.

Secondly, we drew on performance theory to highlight the importance of physical, visual and material performances, like UNFCCC COPs, for creating and maintaining the impression of elite unity and competence in managing global public goods like the climate.

Thirdly, Science and technology studies helped us to consider how to spot opportunities to facilitate rapid transitions by identifying how changing material circumstances bridge differences between previously opposed groups. Equally, the multiple-level perspective, drew our attention to how changing conditions at regime, landscape and local levels might have the opportunity to both disrupt existing alliances and bring seemingly opposed groups together through shared interests.

With these theories, we set out to explore whether we could find cracks in elite forums at COP, explore whether there were strains in these performances and if we could identify potentially new alliances that might come out of opening up these cracks.

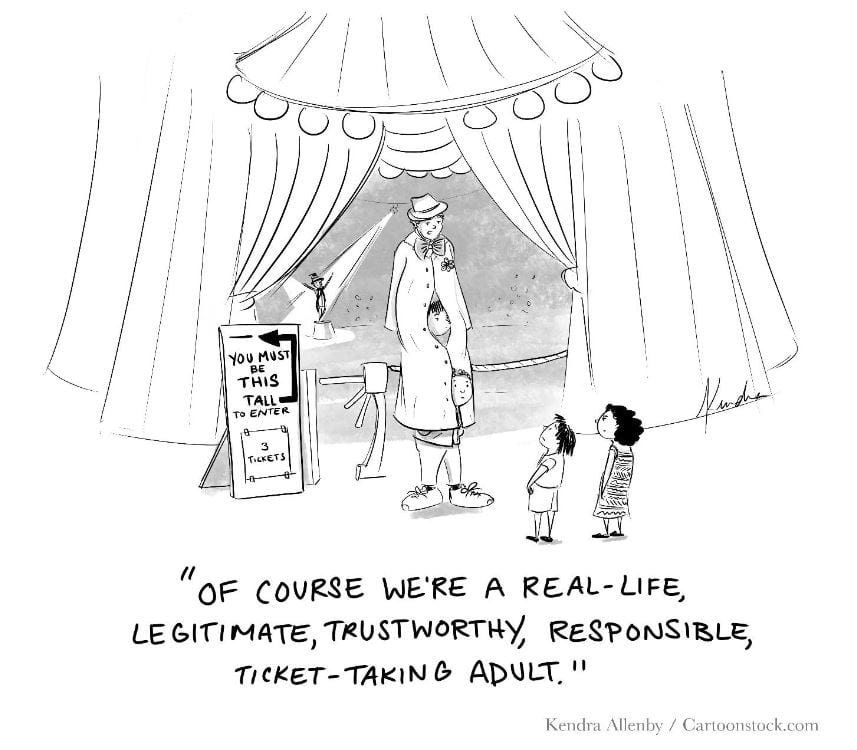

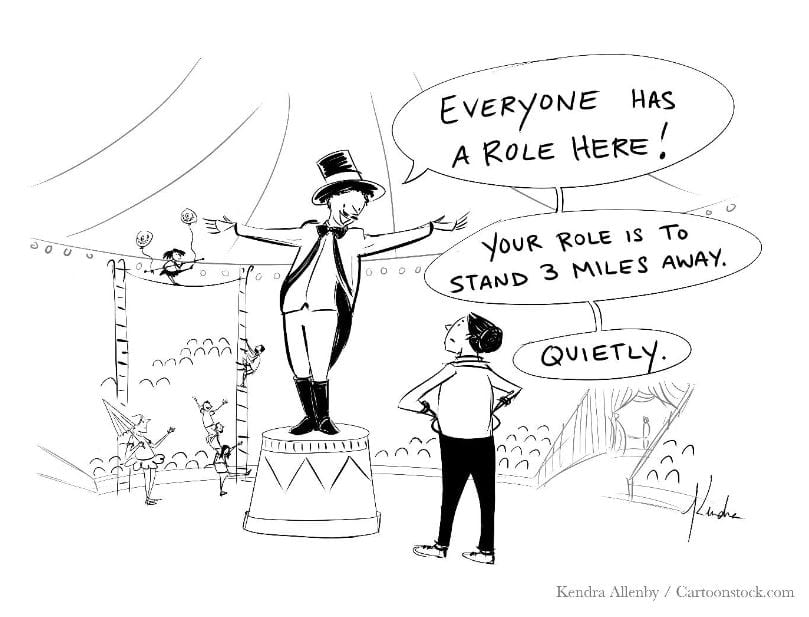

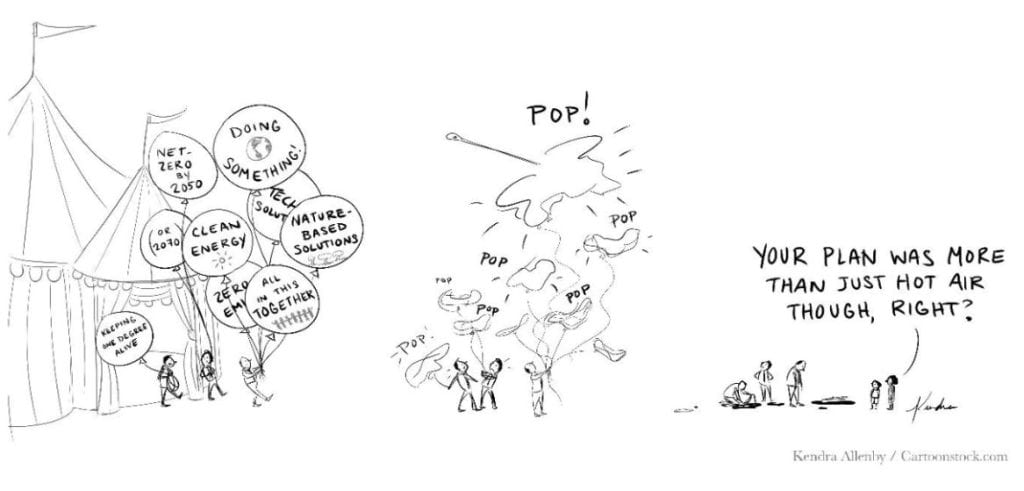

What happens next is described in the rest of this blog and illustrated with cartoons we developed to capture the essence of what we came to think of as the highly vulnerable performances of elite power at COP26.

Performing the COP

What struck us about COP26 was that it was not a coherent space managed and led by a single elite. Instead, it had a multiple, fragmented nature. COP is perhaps best thought of as a bewildering circus of loosely connected activities masquerading as a single event.

This is not surprising. A COP meeting gathers multiple groups with contradictory aims: simultaneously a forum of intergovernmental negotiations, a trade fair for corporate partners and a site of civil society participation and protests.

What is also noticeable, however, is that this fragmentation is hierarchically organised through complex procedures of inclusion and exclusion (Blue Zones, Green Zones, Access Cards, T shirts) with different levels of access accorded to different groups depending on their symbolic importance for validating the COP performance of an inclusive and diverse forum (recognised and acceptable scientists, a selection of key green activists and representatives of youth indigenous peoples). This is stage managed in such a way as to produce a performance that reassures a public watching via television and social media that there is a coherent plan for averting climate disaster.

The hierarchical format of the COP, most clearly expressed through the separation between the Green and Blue Zones, maintains the impression of there being a central heart of power, where decisions are made and the global response is organised. Such an impression produces the performance of the COP as the key forum for climate action, to which interested parties must desire access, and in which those with access must desire ever greater access to the ever elusive and ever more exclusive circle of decision-making. Despite this, the event was characterised in fact by a pluralisation of decision-making activities – by side dinners for particular industries, by one to one meetings, bilateral agreements, and encounters between civil society, academic, policy, media and industry groups.

From this perspective, the ultimate discursive illusion of the COP is that there is a central seat of power, of the governing and corporate elites that come together in a single place to take decisive actions to avert climate change disaster. The selective inclusion of groups like youth, indigenous peoples and green civil society organisations in particular, served to bolster this illusion – creating an impression of participation while reducing them to symbolic speeches and side-events. We call this co-option because, in reality, such groups and individuals appear to have had almost no influence on the outcomes of COP, the Glasgow Climate Pact or the agreement of the Paris Rulebook.

Intra-elite cracks and potential for new alliances

Drawing on Laclau and Mouffe, we mapped out the discursive nodal points that created the equivalences that allowed the highly fractured parties in the discussions to sustain the perception of elite consensus on addressing the climate crisis. Unsurprisingly, they were vague. All organised around the major overarching nodal point – the climate model itself. The key nodal points of the official COP26 were ‘keeping one degree alive’ and ‘achieving net-zero’, with vague references to ‘technological solutions’ and ‘nature-based solutions’ as means of achieving this. These were reiterated in a variety of different formulations across all aspects of the COP – from the public-facing leaders’ stages to online materials to banners and marketing materials throughout the events. A second critical overarching nodal point was the false universalism that diffused responsibility from specific actors and instead presented this as a shared global challenge – the repeated marketing phrases ‘we are all in this together’ and ‘we have to turn anger into action’. This papered over the intra-elite cracks that would emerge between the winners and losers of any genuinely decisive action.

Given the intentional ambiguity of these discursive nodal points, there is unsurprisingly growing debate about what they actually mean, and signs of intra-elite cracks emerging around them. This creates opportunities for civil society groups and others wanting to build alternative strategies to combat the climate emergency.

An example of such a crack is evident in the concept of ‘nature-based solutions’ and what it can mean to different incumbent elite factions. The fossil fuel industry is happy to endorse this phrase, provided that it allows offsets from carbon emissions through reforestation to reach ‘net-zero’. Such an interpretation of nature-based solutions would in practice mean doubling down on current practices which have led to the displacement of indigenous peoples and peasants to make room for offsetting plantations. On the other hand, the insurance industry, which routinely underwrites extractive projects, has grown increasingly aware of its exposure to climate change. We can see an emerging rift between them and their long time fossil fuel partners as they begin to demand that nature-based solutions involve the preservation of biodiverse nature.

At COP we saw some examples of civil society groups seeking to re-articulate and open up the contestation in terms such as ‘nature-based solutions’ and ‘we are all in this together’ as a way of disrupting intra elite relationships. For example, we saw joint activities between the insurance giant Aviva, civil society group Global Canopy and representatives of Amazonian Indigenous peoples speaking of their partnership in identifying companies contributing to deforestation and divesting from them. Such activities take these key terms and make visible the differences in how they might be interpreted in ways that can either enable the preservation of climate destroying practices or empower current custodians of biodiverse nature. Such events successfully undermine the performance of consensus in events such as COP and outline routes towards rearticulating these key terms in ways that allow new alliances to form between marginalised and elite groups.

Reflections

Our team started out with hunches that there were cracks in elite incumbent resistance to serious actions to tackle climate change. What we came away with after using these theoretical tools to make sense of the COP was less a sense of cracks in alliances, and instead a sense of profound fragmentation, disconnection between hugely varied actors and a desperate struggle to create the impression of coherence and the successful performance of control. We were left wondering whether the search for ever greater access to inner sanctums of elite power that seemed to be ever more elusive would be a wise strategy for actors wishing to shift the debate. Instead, starting from an assumption of heterogeneity and disorganisation, of failed performances and illusory central points of power would suggest there are opportunities in thinking horizontally, organising in multiple sites, pluralising and making visible the heterogeneity of decision-making moments. At the same time, rather than simply naming the over-familiar discursive nodal points as ‘blah blah blah’ – recognising them precisely as a key means of organising alliances, the challenge may be to occupy, interpret and reinterpret these terms. If we are all in it together – let’s make it all of us, if we are looking for nature-based solutions – let’s have a conversation about the different meanings of nature and what we are looking for a solution to.

In other words – our sense is that it no longer makes sense to only search for cracks in elite incumbent resistance. But instead – there is merit in starting from the assumption that it is a miracle that alliances are made at all, and working creatively and persuasively to make visible the divides that sit both beneath the performance of events like COP, and the disagreements that sit within the language of consensus. From that, new alliances might be made.

References

Austin, J. L. (1962). How to Do Things with Words. Oxford: University Press.

Bachram H. (2004) Climate fraud and carbon colonialism: the new trade in greenhouse gases, Capitalism Nature Socialism, 15:4: 5-20.

Barry, A. (2002) The anti-political economy, Economy and Society, 31:2: 268-284.

Callon, M, Lascoumes, P and Barthe, Y (2001). Acting in an Uncertain World. An Essay on Technical Democracy. Boston Mass: MIT Press.

Ford, A. and Newell, P. (2021) Regime resistance and accommodation: Toward a neo-Gramscian perspective on energy transitions, Energy Research & Social Science, 79.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, NY:Doubleday.

Golnaraghi, M et. al. (2021) Climate Change Risk Assessment for the Insurance Industry: A holistic decision-making framework and key considerations for both sides of the balance sheet, The Geneva Association: https://www.genevaassociation.org/sites/default/files/research-topics-document-type/pdf_public/climate_risk_web_final_250221.pdf Last accessed on 06.10.2022.

Krauss, A.D. (2021) ‘Chapter 16 – Effect of climate change on the insurance sector’, in ed. Letcher T.M., The Impacts of Climate Change: A Comprehensive Study of Physical, Biophysical, Social, and Political Issues, Bath, UK: Laurel House, Stratton on the Fosse: 397-436.

Laclau, E. and Mouffe, C. (2001). Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards A Radical Democratic Politics. NY: Verso.

Marres N. The Issues Deserve More Credit: Pragmatist Contributions to the Study of Public Involvement in Controversy. Social Studies of Science. 2007; 37(5): 759-780.

Newell, P. (2021). Power Shift: The Global Political Economy of Energy Transitions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Newell, P., & Mulvaney, D. (2013). The political economy of the ‘just transition’. The Geographical Journal, 170(2): 132–140.

Oxfam (2021) ‘Net zero’ carbon targets are dangerous distractions from the priority of cutting emissions says new Oxfam report. Press Releases, 03.08.2021: https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/net-zero-carbon-targets-are-dangerous-distractions-priority-cutting-emissions-says Last accessed on 06.10.2022.

Paterson, M (2001) Risky Business: Insurance Companies in Global Warming Politics, Global Environmental Politics, 1(4): 18–42.

Swilling M. & Annecke E. (2012). Just transitions: explorations of sustainability in an unfair world. Claremont, South Africa, UCT Press.

Turnheim, B. and Sovacool B.K. (2020) Forever stuck in old ways? Pluralising incumbencies in sustainability transitions, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 35: 180-184.

————————-

The authors of this blog have worked on this as “the Carbon Elites Collective”, which includes Aslak-Antti Oksanen (Bristol, SPAIS), Keri Facer (Bristol, School of Education), Peter Newell (University of Sussex), Pablo Suarez (The Red Cross/Red Crescent), María Estrada Fuentes (Royal Holloway), Jeremy Brice (University of Manchester), Antonia Layard (University of Oxford) and Kendra Allenby (freelance cartoonist).