When was the last time you saw a frog? Perhaps you came across one in your garden and wondered at its little hands, glossy skin and what looked very much like a contented smile.

Maybe you regularly see them on Instagram or TikTok, where “frog accounts” have proliferated in recent years. People share adorable cartoon frogs, coo over crocheted frogs or go gaga for frogs dressed in cute hats.

In fact, our fascination with frogs isn’t new. As our research has found, the history of human-frog relations is long and complicated – and not all of it is nice.

Why we love frogs

There is a rich history of people really loving frogs.

This is interesting, because many people much prefer mammals and birds over reptiles and amphibians.

But the frog is an exception – for a lot of reasons. People tend to be attracted to baby-like faces. Many species of frog have the large eyes characteristic of young animals, humans included.

Having no teeth and no sharp claws, they also do not seem to be immediately threatening, while many of them have beautiful skin colouring and some are improbably tiny.

Frogs are truly among the jewels of the natural world, unlike toads which – with their more mundane colours and “warty skins” – do not usually inspire the same sense of enchantment.

Their beauty connects us to the wider riches of a vibrant nature hidden from most people’s sight in the dense rainforests of the tropical regions.

And they also connect us to nature in our own backyards. At certain times of the year, they spontaneously appear in our gardens and ponds. They can feel like special visitors from the natural world.

Dissecting human feelings for frogs

Yet relationships between people and frogs haven’t always been so positive. In fact, frogs occupy complicated places across cultures all over the world.

In the Western tradition, the legacy of biblical and classical sources was both negative and longstanding.

References to frogs in the Bible rendered them the instrument of divine anger as a swarming plague.

Wellcome Collection

Frogs challenged early modern zoological taxonomies, moving between classification as serpent, insect or reptile.

Perhaps their resistance to easy placement by humans explains the strong emotional language about them used by Swedish naturalist (and “father of modern taxonomy”) Carl Linnaeus.

When he considered the Amphibia in his 1758 Systema Naturae, he noted:

These foul and loathsome animals are abhorrent because of their cold body, pale colour, cartilaginous skeleton, filthy skin, fierce aspect, calculating eye, offensive smell, harsh voice, squalid habitation, and terrible venom.

In modern science, they sit in a branch of zoology, herpetology, that brings frogs together as “creeping animals” with snakes and lizards.

Frogs have also (or perhaps consequently) suffered in the service of science since at least the eighteenth century because it seemed to be possible to easily replicate experiments across multiple frog specimens.

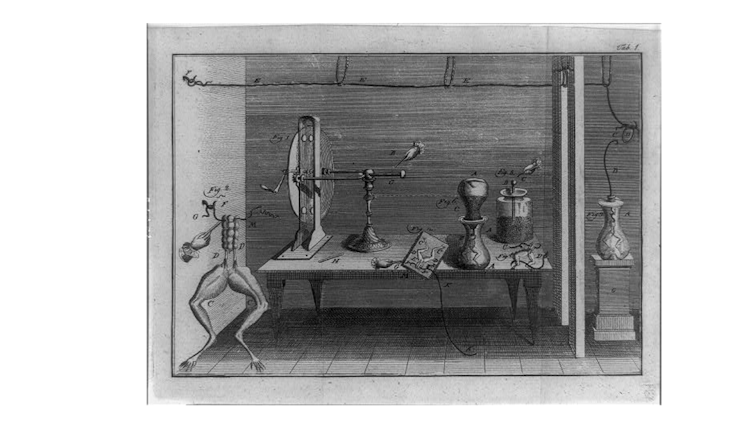

Frogs were particularly crucial to the study of muscles and nerves. This led to ever more violent encounters between experimenters and frog bodies. Italian scientist Luigi Galvani, for example, did experiments in the late 18th century on legs of frogs to investigate what he thought of as “animal electricity”.

Library of Congress

In this sense, frogs were valued as significant scientific objects, their value lying in their flesh, their nervous systems, rather than in their status as living, feeling beings in the world.

In time, experiments with frogs moved beyond the laboratory into the classroom. In the 1930s, schoolchildren were expected to find frogs and bring them to school for dissection in biology classes.

This practice was, however, somewhat controversial, with opponents expressing sentimental attachment to frogs and concerns that such animal cruelty would lead to barbarism.

Recognising the fragility of frogs

So, our relationship with frogs is complicated. From the frogs of Aesop’s Fables to the meme Pepe the Frog, we have projected our own feelings and frustrations onto frogs, and exploited them for science and education.

Frogs have also borne the brunt of our failures as environmental stewards.

By 1990, the world was seeing a global pattern of decline in frog populations due to destruction and degradation of habitat for agriculture and logging, as well as a global amphibian pandemic caused by the chytrid fungus.

Climate change is also making life hard for many species. In 2022, over 40% of amphibian species (of which frogs and toads are by far the largest group) were threatened with extinction. Their vulnerability has seen the frog – especially the red-eyed tree frog – become a symbol for the environment more generally.

So we should delight in frogs and marvel at how beautiful and special they are while we still can, and consider how we might help save them.

Something to reflect on next time you are lucky enough to spot a frog.![]()

—————————–

This blog is written by Susan Broomhall, Director, Gender and Women’s History Research Centre, Australian Catholic University; Andrea Gaynor, Professor of History, The University of Western Australia, and Cabot Institute for the Environment member, Dr Andy Flack, Senior Lecturer in Modern and Environmental History, University of Bristol. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.