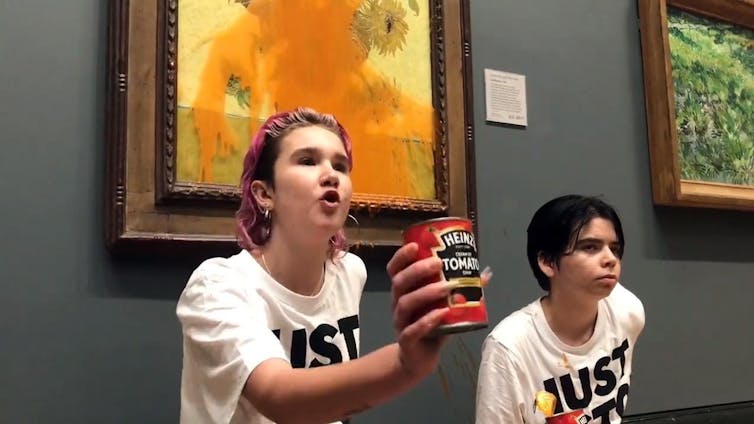

Two Just Stop Oil activists were recently jailed for 27 months and 20 months respectively for throwing soup at one of Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers paintings at London’s National Gallery back in October 2022. Some commentators suggested these were overly harsh sentences for a nonviolent protest, while others felt such sentences were appropriate and an important deterrent.

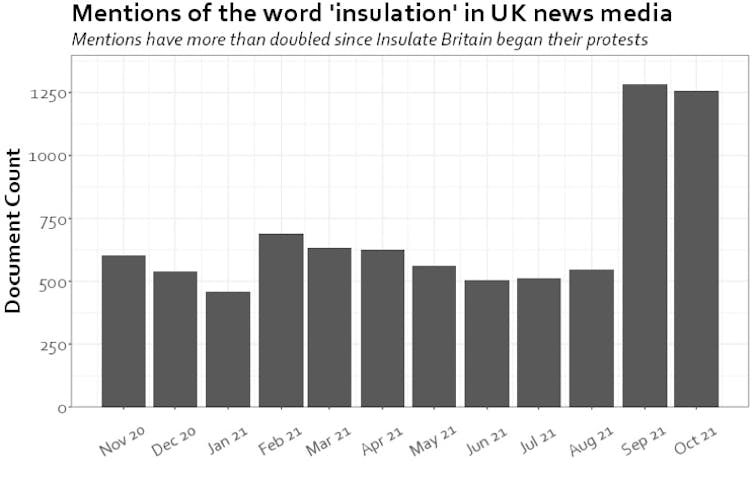

We study activism and its impact (and sometimes have participated in direct actions like these). In our latest research, we looked at 42 climate protests at museums and art galleries in Europe, the US, Canada and Australia between 2022 and 2024. We wanted to know what makes this form of protest so unpopular with the general public, and why climate activists have continued to return to galleries despite, or even because of, the resulting social outrage.

As it happens, we published our work in the journal Protest just a few days before the Just Stop Oil activists were sentenced.

One common theme we found is that such protests are widely criticised because of their supposed irrationality. For instance, in his sentencing remarks in the Sunflowers case, Judge Christopher Hehir spoke for many when he described the soup-throwing action as “criminally idiotic”.

However, we should consider the logic offered by the activists themselves. The video of the action in October 2022 shows one of them, Phoebe Plummer, asking: “What is worth more – art or life? Is [art] worth more than food, more than justice?”

The judge claimed these words revealed “how little the [protesters] cared about Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, or art generally”. This seems an odd misunderstanding. The question of which is worth more – art or life – only warrants interest because the value of life is being compared to objects that are considered to be the most valuable products of human culture. We wouldn’t be having this conversation if Just Stop Oil had thrown soup over a less-heralded artwork.

Why is (apparent) art destruction so powerful?

Throwing soup at paintings is extremely unpopular. We recently commissioned a YouGov poll in which 2,048 representative members of the public were asked about 15 different forms of climate protest. Throwing food at paintings was considered the least justifiable of these protests – less justifiable than sabotaging pipelines, damaging private jets or breaking windows at companies financing oil exploration.

The extreme unpopularity of throwing soup at Sunflowers virtually guaranteed that it would have an audience of millions. Although commentators worried that such an unpopular action would turn people away from the cause, there is no evidence for such an impact. The public may hate the messengers and their actions, but they’re nevertheless exposed to the message.

Indeed, we suspect the reason activists target art is directly related to why it is so unpopular. In academic psychology, terror management theory suggests that damaging revered cultural symbols threatens the psychological defences we rely on to mitigate existential fears.

Think of how memorials are built to soldiers who die in war, to offer them a form of symbolic immortality (“they shall not grow old”), and the way any threat to desecrate such memorials is met with strong condemnation.

Masterpieces like Sunflowers offer a similar sense of immortality and permanence. In a way, our veneration of his work means that Van Gogh is still alive, and its preservation means our culture will live on after our own demise. This explains why the apparent destruction of art provokes such a strong backlash, and why activists use the spectacle to draw parallels between cultural and environmental preservation.

It seems the symbolic value of the painting was an important factor in Judge Hehir’s sentencing. In his words:

It is not the value of the damage caused to the frame that is the most serious aspect of your offending … [Van Gogh’s] work is part of humanity’s shared cultural treasure … you came within the thickness of a pane of glass of irreparably damaging or even destroying this priceless treasure, and that must be reflected in the sentences I pass.

Punishment should fit the crime

Another YouGov poll conducted in July 2023 found fewer than 30% of the UK public think prison sentences are appropriate for nonviolent protesters; only 6% favour sentences of “more than a year in prison”. Over twice as many (15%) don’t believe there should be any punishment for nonviolent protest.

The appropriate punishment for radical dissent should be a matter of concern for all of us. Punishment is not only about retribution. It also communicates societal disapproval. Judge Hehir said: “Sentences must be imposed which both adequately punish you for what you did, and what you risked, and which will deter others whose motivations may incline them to similar behaviour.”

In the immediate aftermath of the sentencing of Plummer and her co-defendant Anna Holland, another three Just Stop Oil activists visited the same gallery in London. They have been charged with criminal damage after soup was thrown at the protective glass of two other paintings by Van Gogh.

Solidarity protests happened in Norway, Sweden, Canada and Germany. Rather than deterring activists, in the immediate term the sentencing seemed to backfire by causing more protests.

These protests trigger a powerful desire for punishment and condemnation. But society would benefit from a sincere attempt to understand the rationale and motivations of those activists who seem to go beyond the normal bounds of protest. Deterrence will not work for those who are acting by their own moral imperatives. It will not stop those climate activists who are drawn to radical symbolic action in order to interrupt the “business as usual” that is leading toward the destruction of both art and life.

This blog is written by Alexander Araya López, Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Potsdam and Cabot Institute for the Environment member Colin Davis, Chair in Cognitive Psychology, University of Bristol. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.