On 15 October 2014, we had a fascinating talk from Prof. Wendy Gibson from the University of Bristol’s School of Biological Sciences launching the University’s ‘Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction: Capacity Building in the face of Environmental Uncertainty’ network.

The Cabot Institute is supporting a number of ventures to foster an interdisciplinary network of academics across the University, whose work can be included under the broad ‘development studies’/’international development’ umbrella, due to its direct or indirect impact on sustainable development and poverty reduction in the Global South.

Uniquely, at Bristol, this includes academics working in the social sciences, but also in Physical Geography, Earth Sciences, Public Health, Engineering, Biological and Veterinary Sciences, to name but a few. This ‘International Development Discussion Forum’ will have a regular monthly slot and it is therefore hoped that participants will come regularly, not because they may be specialists in the topic of that month’s presentation, but in order to hear the kinds of questions that parasitologists, or engineers, or lawyers, for example, raise for development research; questions that they can, in turn, contribute to from their own discipline.

Coping with parasitic diseases in Africa

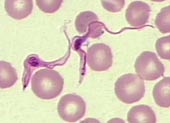

The topic of Wendy’s talk was the extensive research she has undertaken as a parasitologist on the tsetse fly as a vector for trypanosomes, parasites which cause African sleeping sickness, or HAT – Human African Trypanosomiasis. In light of the global media coverage of the Ebola outbreak, Wendy’s measured reminder about the ongoing impact of a lower profile disease such as HAT, on people and animals in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa, was sobering. Not only does the disease have a devastating impact on affected communities, but diagnosis and the treatment of the disease are extremely unpleasant and involve protracted intervention. In situations in which people are coping with a range of daily hardships that impact upon their livelihoods, including drought, poor forage and a range of different diseases affecting human and animal populations, disease-focused approaches often fail to recognise this reality.

Interdisciplinary challenges in rural healthcare

After the talk, participants were asked to focus on three specific challenges identified by Wendy:

- How to maintain momentum in control programs as we move towards disease eradication.

- How to prioritise disease risks with a finite health budget.

- How to get different government departments to co-operate on shared goals.

Given that the subject clearly raised so many issues relating to the challenges of public health care in sub-Saharan Africa – including issues relating to rural (as opposed to urban) poverty, governance and the state, aid and non-governmental organisations – discussions were wide-ranging. Rather than proffering standard academic critique of the material presented, participants were asked to focus on what they, positioned as they are within their own discipline, could bring to the table. Consequently, it was fascinating how different tables touched upon similar issues but nevertheless raised specific insights depending on the differing make-up of the tables and the expertise included on them.

Specific challenges identified included:

- ongoing problems with top-down interventions,

- the forging of rural (and regional) networks,

- the difficulties in specifying the costs of such a disease,

- raising the profile of a such a low-profile disease when its symptoms may take some years to become manifest, and

- the difficulties of co-ordinating NGOs, aid, and governments in relation to healthcare priorities, particularly when healthcare demands are seen to ‘compete’ with each other.

And discussions continued into the networking drinks as participants identified a number of practical and funding obstacles in undertaking the kind of real interdisciplinary research that could be of such value in responding to some of the challenges relating to a disease such as African sleeping sickness.

Quotes from participants

“I knew that some of my research might be usefully applied in developing countries, but the complex challenges and the feeling that I lack a track record in ‘development research’ put me off. Through the forum I am learning about that world, and it has been a real eye-opener. I had no idea that so much was going on across the University in this area, nor that my naivety would be treated so generously in the friendly and open discussions that we’ve had so far.”

“As a scientist I want my work to be “useful”. However, translating knowledge into effective and successful, practical outcomes takes more than just generation of that scientific knowledge. This is being increasingly recognised by funders, many of whom now have a focus on interdisciplinarity, particularly for delivering outcomes that can make a difference to people living in developing countries (e.g. the Newton Fund, but also some Research Council funding calls). While the topic of this workshop was not within my scientific field, it was fascinating, and gave me insight into the realities and difficulties of implementing change that really does require the bringing together of many different aspects of knowledge. I met some colleagues that would be great to collaborate with in the future in order to better deliver effective outcomes.”

Dr. Jo House, Geographical Sciences

Future discussion

On 11 November 2014, the Cabot Institute will be supporting the next discussion forum in this series in which Prof. Thorsten Wagener will be giving a talk on his ongoing work in the field of sustainable water management. His research focuses on a systems approach, which he argues is needed to adequately understand this dynamic physical and socio-economic system with the goal to provide water security for people and nature.

—————————–

This blog has been written by Dr Elizabeth Fortin, Cabot Institute, University of Bristol Law School.