Fresh morning, new sights

Interconnected beauty

Time to scratch below[1]

When do we really give ourselves time to reflect? Deeply. As academics we think a great deal, but how often do we immerse ourselves in our immediate environment and open ourselves to the profound possibilities of interdisciplinary exchange?

A rare opportunity to do just that was offered via a Cabot Institute for the Environment workshop earlier this year. Run in conjunction with the ‘Environmental Keywords’ project team (PI: Dr Paul Merchant, Modern Languages, Co-I: Professor Daniela Schmidt, Earth Sciences and Senior Research Associate: Dr Claire Cox, English Literature), the session sought to unpack how terms commonly-used used in communications on climate change are variously perceived, and what they might be understood to mean.

As academics engaged in urgent environmental challenges, our interdisciplinary communications can too often stall on discipline-specific definitions across, for example, the humanities and hard sciences. Our half-day workshop sought to open a shared space for interdisciplinary exchange by focussing on the word ‘vulnerability’ as a starting point towards co-created understandings that have the potential to catalyse new interdisciplinary collaborations, and, more widely, to inform local policy makers’ thinking.

Environmental Keywords: Phase 1 Community Workshops

The Cabot workshop marked the launch of the second phase of the Environmental Keywords project (also supported by Research England’s Policy Support Fund). The first phase, funded by NERC (Natural Environment Research Council), took place in 2021-22 and comprised a series of three Bristol-based community workshops which explored how a creative facilitation methodology grounded in key terms in environmental research and activism (such as ‘resilience’, ‘justice’ and ‘transitions’) might enhance community engagement with contemporary environmental challenges. These workshops were held across the city with community partner organisations including Heart of BS13 and Eastside Community Trust, and included colleagues from a range of disciplinary backgrounds from the University of Bristol.

Key to the co-creation approach was an introductory ‘Walk and Talk’ activity around the community groups’ localities. Crucially, the walks not only acknowledged the group members’ as leaders and experts on their own terms, but also provided shared points of reference for later round-table discussions. From these free-flowing discussions it became clear that for many of the community participants survival considerations, such as the cost of living and physical safety, were more pressing than, what were perceived as, the distant and abstract threats of climate change.

The Cabot ‘Walk and Talk’

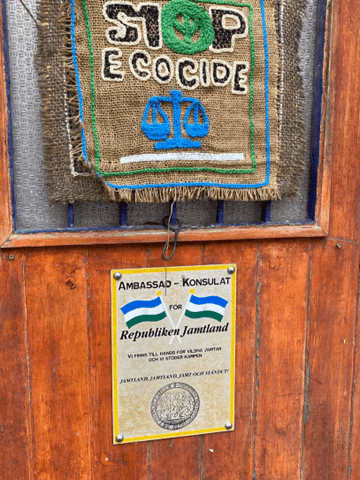

As Robert Macfarlane observed: ‘walking is not the action by which one arrives at knowledge; it is itself the means of knowing.’[2]. For the Cabot workshop we again employed the walking methodology; and with ‘vulnerability’ in mind, took a route from Royal Fort House to King Square, returning past the Bristol hospitals via Marlborough Street. This gave us ample opportunity to chat, as well as to observe our surroundings, make notes and take photographs of things that exemplified ‘vulnerability’ to us or sparked our interest.

Round table reflections

Emergent themes from the discussion that followed our walk were as insightful as they were wide-ranging. Much of the consideration centred around vulnerabilities arising from poverty and socio-economic disparities locally and globally; and the associated issues of power and power structures, agency, lack of choice and who decides on the choices we have.

Physical vulnerabilities, as prompted by Bristol’s steep topography from sea level to hilltop, were also deliberated, as were ideas about differing perceptions of our own vulnerability, often based on gender, health or age. We noted that people can also refuse to recognize their own vulnerability for many reasons.

As we had walked though Bristol’s Clean Air Zone issues including pollution, policy, public health, equity and political transparency quickly came to the fore. The shifting dynamics between vulnerability and reliance were also discussed, as was loss of the commons and of green spaces globally.

The complexity of the climate crisis was framed in terms of Rob Nixon’s concept of ‘slow violence’ and difficulties of responding to such an incremental set of environmental threats [3]. There was also a sense that as a concerned group of individuals, we need to understand vulnerability in order to achieve social justice; and that interdisciplinarity can open us to new ways of perceiving and understanding the world beyond the limitations of our personal inclinations and disciplinary boundaries.

Saying it with syllables

To round off the session, and as a creative counterpoint to the intensity of the workshop, there was an invitation to describe a ‘moment of delight’ from the walk and to express it in the form of a haiku: an ancient and very short poetic form synonymous with Japan, based on a pattern of syllables over three lines.

Almost immediately another, unexpected, vulnerability was highlighted – that of language. Several of the group’s English-as-an-additional-language speakers encountered issues around thinking ‘poetically’ in another language. Here, writing in one’s birth language came more easily, with the poem then being translated into English. Environmental Keywords’ exploration into the relationship between the words we use and the thoughts we seek to express suddenly became very tangible indeed.

Voy adelante

ciudad nueva, cielo gris

me pierdo – no soy

I walk on

new city, grey skies

I get lost – I am not [4]

[1] Haiku from Cabot workshop.

[2] Robert Macfarlane, The Old Ways (London: Penguin Books Ltd, 2013), p. 27.

[3] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2011).

[4] Portuguese/English haiku from workshop.

———————————-

This blog is written by Cabot Institute for the Environment member Dr Claire Cox at the University of Bristol.