Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has increased abruptly in the past two years, after having been on a downward trajectory for more than a decade. With the country’s president Jair Bolsonaro notoriously enthusiastic about expanding into the rainforest, new deforestation data regularly makes global headlines.

But what fewer people realise is that even forests that have not been cleared, or fully “deforested”, are rarely untouched. Indeed, just 20% of the world’s tropical forests are classified as intact. The rest have been impacted by logging, mining, fires, or by the expansion of roads or other human activities. And all this can happen undetected by the satellites that monitor deforestation.

These forests are known as “degraded”, and they make up an increasingly large fraction of the world’s remaining forest landscapes. Degradation is a major environmental and societal challenge. Disturbances associated with logging, fire and habitat fragmentation are a significant source of CO₂ emissions and can flip forests from carbon sinks to sources, where the carbon emitted when trees burn or decompose outweighs the carbon taken from the atmosphere as they grow.

Forest degradation is also a major threat to biodiversity and has been shown to increase the risk of transmission of emerging infectious diseases. And yet despite all of this, we continue to lack appropriate tools to monitor forest degradation at the required scale.

CIFOR / flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

The main reason forest degradation is difficult to monitor is that it’s hard to see from space. The launch of Nasa’s Landsat programme in the 1970s revealed – perhaps for the first time – the true extent of the impact that humans have had on the world’s forests. Today, satellites allow us to track deforestation fronts in real time anywhere in the world. But while it’s easy enough to spot where forests are being cleared and converted to farms or plantations, capturing forest degradation is not as simple. A degraded forest is still a forest, as by definition it retains at least part of its canopy. So, while old-growth and logged forests may look very different on the ground, seen from above they can be hard to tell apart in a sea of green.

Degradation detectives

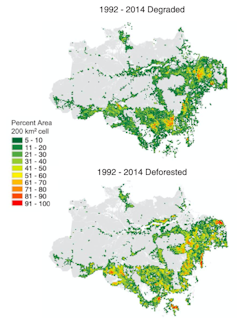

New research published in the journal Science by a team of Brazilian and US researchers led by Eraldo Matricardi has taken an important step towards tackling this challenge. By combining more than 20 years of satellite data with extensive field observations, they trained a computer algorithm to map changes in forest degradation through time across the entire Brazilian Amazon. Their work reveals that 337,427 km² of forest were degraded across the Brazilian Amazon between 1992 and 2014, an area larger than neighbouring Ecuador. During this same period, degradation actually outpaced deforestation, which contributed to a loss of a further 308,311 km² of forest.

The researchers went a step further and used the data to tease apart the relative contribution of different drivers of forest degradation, including logging, fire and forest fragmentation. What these maps reveal is that while overall rates of degradation across the Brazilian Amazon have declined since the 1990s – in line with decreases in deforestation and associated habitat fragmentation – rates of selective logging and forest fires have almost doubled. In particular, in the past 15 years logging has expanded west into a new frontier that up until recently was considered too remote to be at risk.

Matricardi et al

By putting forest degradation on the map, Matricardi and colleagues have not only revealed the true extent of the problem, but have also generated the baseline data needed to guide action. Restoring degraded forests is central to several ambitious international efforts to curb climate change and biodiversity loss, such as the UN scheme to pay developing countries to keep their forests intact. If allowed to recover, degraded forests, particularly those in the tropics, have the potential to sequester and store large amounts of CO₂ from the atmosphere – even more so than their intact counterparts.

Simply allowing forests to naturally regenerate can be a very effective strategy, as biomass stocks often recover within decades. In other cases, active restoration may be a preferable option to speed up recovery. Another recent study, also published in the journal Science, showed how tree planting and cutting back lianas (large woody vines common in the tropics) can increase biomass recovery rates by as much as 50% in south-east Asian rainforests. But active restoration comes at a cost, which in many cases exceeds the prices that are paid to offset CO₂ emission on the voluntary carbon market. If we are to successfully implement ecosystem restoration on a global scale, governments, companies and even individuals need to think carefully about how they value nature.![]()

———————————-

This blog is written by Cabot Institute member Dr Tommaso Jucker, Research Fellow and Lecturer, School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Tommaso Jucker |