Misinformation is debated everywhere and has justifiably sparked concerns. It can polarise the public, reduce health-protective behaviours such as mask wearing and vaccination, and erode trust in science. Much of misinformation is spread not by accident but as part of organised political campaigns, in which case we refer to it as disinformation.

But there is a more fundamental, subversive damage arising from misinformation and disinformation that is discussed less often.

It undermines democracy itself. In a recent paper published in Current Opinion in Psychology, we highlight two important aspects of democracy that disinformation works to erode.

The integrity of elections

The first of the two aspects is confidence in how power is distributed – the integrity of elections in particular.

In the United States, recent polls have shown nearly 70% of Republicans question the legitimacy of the 2020 presidential election. This is a direct result of disinformation from Donald Trump, the loser of that election.

Democracy depends on the people knowing that power will be transferred peacefully if an incumbent loses an election. The “big lie” that the 2020 US election was stolen undermines that confidence.

Depending on reliable information

The second important aspect of democracy is this – it depends on reliable information about the evidence for various policy options.

One reason we trust democracy as a system of governance is the idea that it can deliver “better” decisions and outcomes than autocracy, because the “wisdom of crowds” outperforms any one individual. But the benefits of this wisdom vanish if people are pervasively disinformed.

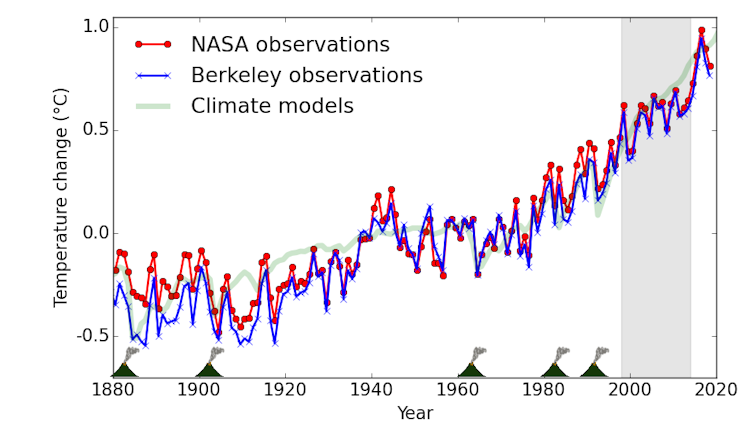

Disinformation about climate change is a well-documented example. The fossil fuel industry understood the environmental consequences of burning fossil fuels at least as early as the 1960s. Yet they spent decades funding organisations that denied the reality of climate change. This disinformation campaign has delayed climate mitigation by several decades – a case of public policy being thwarted by false information.

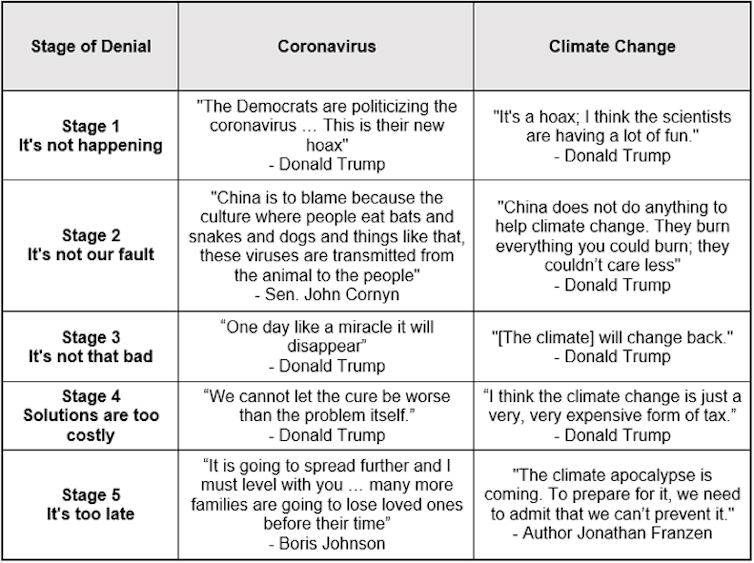

We’ve seen a similar misinformation trajectory in the COVID-19 pandemic, although it happened in just a few years rather than decades. Misinformation about COVID varied from claims that 5G towers rather than a virus caused the disease, to casting doubt on the effectiveness of lockdowns or the safety of vaccines.

The viral surge of misinformation led to the World Health Organisation introducing a new term – infodemic – to describe the abundance of low-quality information and conspiracy theories.

A common denominator of misinformation

Strikingly, some of the same political operatives involved in denying climate change have also used their rhetorical playbook to promote COVID disinformation. What do these two issues have in common?

One common denominator is suspicion of government solutions to societal problems. Whether it’s setting a price on carbon to mitigate climate change, or social distancing to slow the spread of COVID, contrarians fear the policies they consider to be an attack on personal liberties.

An ecosystem of conservative and free-market think tanks exists to deny any science that, if acted on, has the potential to infringe on “liberty” through regulations.

There is another common attribute that ties together all organised disinformation campaigns – whether about elections, climate change or vaccines. It’s the use of personal attacks to compromise people’s integrity and credibility.

Election workers in the US were falsely accused of committing fraud by those who fraudulently claimed the election had been “stolen” from Trump.

Climate scientists have been subject to harassment campaigns, ranging from hate mail to vexatious complaints and freedom-of-information requests. Public health officials such as Anthony Fauci have been prominent targets of far-right attacks.

The new frontier in attacks on scientists

It is perhaps unsurprising there is now a new frontier in the attacks on scientists and others who seek to uphold the evidence-based integrity of democracy. It involves attacks and allegations of bias against misinformation researchers.

Such attacks are largely driven by Republican politicians, in particular those who have endorsed Trump’s baseless claims about the 2020 election.

The misinformers are seeking to neutralise research focused on their own conduct by borrowing from the climate denial and anti-vaccination playbook. Their campaign has had a chilling effect on research into misinformation.

How do we move on from here?

Psychological research has contributed to legislative efforts by the European Union, such as the Digital Services Act or Code of Practice, which seek to make democracies more resilient against misinformation and disinformation.

Research has also investigated how to boost the public’s resistance to misinformation. One such method is inoculation, which rests on the idea people can be protected against being misled if they learn about the rhetorical techniques used to mislead them.

In a recent inoculation campaign involving brief educational videos shown to 38 million citizens in Eastern Europe, people’s ability to recognise misleading rhetoric about Ukrainian refugees was frequently improved.

It remains to be seen whether these initiatives and research findings will be put to use in places like the US, where one side of politics appears more threatened by research into misinformation than by the risks to democracy arising from misinformation itself.

We’d like to acknowledge our colleagues Ullrich Ecker, Naomi Oreskes, Jon Roozenbeek and Sander van der Linden who coauthored the journal article on which this article is based.![]()

Stephan Lewandowsky, Chair of Cognitive Psychology, University of Bristol and John Cook, Senior Research Fellow, Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.