Climate and environmental protest is being criminalised and repressed around the world. The criminalisation of such protest has received a lot of attention in certain countries, including the UK and Australia. But there have not been any attempts to capture the global trend – until now.

We recently published a report, with three University of Bristol colleagues, which shows this repression is indeed a global trend – and that it is becoming more difficult around the world to stand up for climate justice.

This criminalisation and repression spans the global north and south, and includes more and less democratic countries. It does, however, take different forms.

Our report distinguishes between climate and environmental protest. The latter are campaigns against specific environmentally destructive projects – most commonly oil and gas extraction and pipelines, deforestation, dam building and mining. They take place all around the world.

Climate protests are aimed at mitigating climate change by decreasing carbon emissions, and tend to make bigger policy or political demands (“cut global emissions now” rather than “don’t build this power plant”). They often take place in urban areas and are more common in the global north.

Four ways to repress activism

The intensifying criminalisation and repression is taking four main forms.

1. Anti-protest laws are introduced

Anti-protest laws may give the police more powers to stop protest, introduce new criminal offences, increase sentence lengths for existing offences, or give policy impunity when harming protesters. In the 14 countries we looked at, we found 22 such pieces of legislation introduced since 2019.

2. Protest is criminalised through prosecution and courts

This can mean using laws against climate and environmental activists that were designed to be used against terrorism or organised crime. In Germany, members of Letzte Generation (Last Generation), a direct action group in the mould of Just Stop Oil, were charged in May 2024 with “forming a criminal organisation”. This section of the law is typically used against mafia organisations and had never been applied to a non-violent group.

In the Philippines, anti-terrorism laws have been used against environmentalists who have found themselves unable to return to their home islands.

Criminalising protest can also mean lowering the threshold for prosecution, preventing climate activists from mentioning climate change in court, and changing other court processes to make guilty verdicts more likely. Another example is injunctions that can be taken out by corporations against activists who protest against them.

3. Harsher policing

This stretches from stopping and searching to surveillance, arrests, violence, infiltration and threatening activists. The policing of activists is carried out not just by state actors like police and armed forces, but also private actors including private security, organised crime and corporations.

In Germany, regional police have been accused of collaborating with an energy giant (and its private fire brigade) to evict coal mine protesters, while private security was used extensively in policing anti-mining activists in Peru.

4. Killings and disappearances

Lastly, in the most extreme cases, environmental activists are murdered. This is an extension of the trend for harsher policing, as it typically follows threats by the same range of actors. We used data from the NGO Global Witness to show this is increasingly common in countries including Brazil, Philippines, Peru and India. In Brazil, most murders are carried out by organised crime groups while in Peru, it is the police force.

Protests are increasing

To look more closely at the global picture of climate and environmental protest – and the repression of it – we used the Armed Conflicts Location Event database. This showed us that climate protests increased dramatically in 2018-2019 and have not declined since. They make up on average about 4% of all protest in the 81 countries that had more than 1,000 protests recorded in the 2012-2023 period:

Berglund et al; Data: ACLED, CC BY-SA

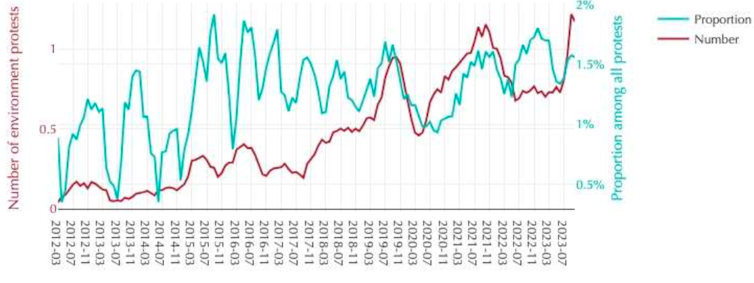

This second graph shows that environmental protest has increased more gradually:

Data: ACLED, CC BY-SA

We used this data to see what kind of repression activists face. By looking for keywords in the reporting of protest events, we found that on average 3% of climate and environmental protests face police violence, and 6.3% involve arrests. But behind these averages are large differences in the nature of protest and its policing.

A combination of the presence of protest groups like Extinction Rebellion, who often actively seek arrests, and police forces that are more likely to make arrests, mean countries such as Australia and the UK have very high levels of arrest. Some 20% of Australian climate and environmental protests involve arrests, against 17% in the UK – with the highest in the world being Canada on 27%.

Meanwhile, police violence is high in countries such as Peru (6.5%) and Uganda (4.4%). France stands out as a European country with relatively high levels of police violence (3.2%) and low levels of arrests (also 3.2%).

In summary, while criminalisation and repression does not look the same across the world, there are remarkable similarities. It is increasing in a lot of countries, it involves both state and corporate actors, and it takes many forms.

This repression is taking place in a context where states are not taking adequate action on climate change. By criminalising activists, states depoliticise them. This conceals the fact these activists are ultimately right about the state of the climate and environment – and the lack of positive government action in these areas.![]()

——————————————

This blog is written by Cabot Institute for the Environment member, Dr Oscar Berglund, Senior Lecturer in International Public and Social Policy, University of Bristol and Tie Franco Brotto, PhD Candidate, School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.