| Coriander has a distinctive flavour and is popular in dishes such as curry. (Image By Deeptimanta (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons) |

Coriander is the UK’s top-selling culinary herb, an industry worth £18 million a year. However, maintaining high standards of product quality is expensive and can lead to lots of plants being rejected before they make it to supermarket shelves. One of the key objectives for the potted herb industry is the production of compact plants with dark green leaves, but the plants that consumers end up with often do not conform with this ideal and can appear leggy and weak.

Plants compete for light by growing taller

Plants go to extraordinary lengths to maximise their light capture for photosynthesis. When plants grow close together however, they compete for resources and one resource that becomes limited in closely spaced plants is light due to mutual shading.

Shade has a negative impact on a plant’s health as it limits the light that a plant can use for photosynthesis. But unlike animals, which can move to new areas once space, water or food becomes limited, plants are immotile and have evolved unique strategies to compete for and maximise light capture. Chief among these is the shade avoidance syndrome. Incredibly, plants anticipate that they are at risk of being shaded even before they actually are shaded through the detection of local light quality – the depletion of red and blue light and the relative enrichment of longer wavelengths of light due to the absorption and reflection properties of vegetation. The shade avoidance syndrome is triggered in response to this change in light quality and the most dramatic changes in plant form involve the elongation of stems and the raising of leaves so as to move light capturing organs into sunlight.

Elongation does have drawbacks however – resources are diverted away from seed, chlorophyll and leaf production; there is also an increased risk of lodging (where plants fall over due to over-elongation making them unable to support their organs), which puts a limit on how densely we can plant crops before they over-compete with each other and it impacts yields.

UV-B suppresses elongation

On the other hand, plants have mechanisms in place to prevent over-elongation. These are often related to light-quality as well and one such mechanism is the sensing of UV-B wavelengths.

Classical Ultra-Violet research on plants has focused on the damaging effects that this shorter wavelength, higher energy light can have on DNA, or cell structure through production of reactive oxygen species. These UV-B wavelengths are beyond our visible range, but plants have specific photoreceptors that can detect UV-B and trigger a signaling cascade that will lead to the accumulation of sun screening compounds as well as architectural changes. Indeed, it is now clear that the plant responses to UV-B are not only a reaction to UV-B damage, but also a specific response to the sensing of UV-B (read more on this on the UV4Plants society website).

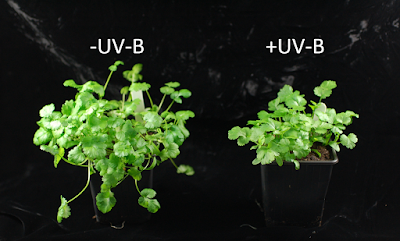

A finding that emerged from our laboratory in Bristol was that the elongation that plants exhibited in crowded conditions could be suppressed with the addition of UV-B to their light conditions (Hayes et al., 2014). UV-B is a component of direct sunlight, so an interpretation of this adaptation is that plants use UV-B as a signal that they are in direct sunlight and hence no longer need to elongate to escape shade.

Applying our research to the glasshouse

Armed with this new knowledge of plant responses to light, we are collaborating with a major potted herb grower to improve their product quality. A problem with glasshouse grown coriander in the winter months is that they grow long and spindly. Often these herbs are planted densely with around 60 seedlings per pot – conditions that are conducive to shade avoidance. Short days and cloud cover during winter further contribute to over-elongation. To compound this, many materials used in glasshouse construction such as glass or clear acrylic filter out UV-B radiation. Thus, plants growing in these conditions are no longer receiving the UV-B brake on elongation that they would be if they were growing outdoors. If we restore this brake by using artificial UV-B light sources then we could solve this problem. We’ve started trialing UV-B treatments this summer and early results look promising. However, we need to wait until winter to collect our most informative data as in summer, with bright and long days, coriander plants grow far more compact than in winter.

|

| Both pots were planted at the same density, the coriander on the left were grown in normal conditions while the coriander on the right were supplemented with UV-B radiation. |

Hayes S, Velanis CN, Jenkins GI, Franklin KA. UV-B detected by the UVR8 photoreceptor antagonises auxin signalling and plant shade avoidance. Proc Natl Acad U.S.A. 2014. 111(32):11894-9

—————————-

This blog is written by Cabot Institute member Donald Fraser who is a PhD student in the Department of Life Sciences at the University of Bristol, he is studying plant responses to light and the circadian clock.