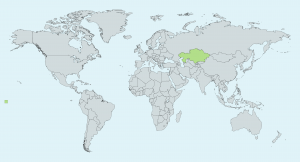

This is the second of a series of blogs from a group of University of Bristol Cabot Institute researchers who are on a remote expedition (funded by BCAI) to find out more about Kazakh agriculture and how farmers are responding to their changing landscape.

|

| Image credit: Hannah Vineer |

Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ played on the car radio as we drove through endless fields of stubble stretching into the horizon in every direction. We were 2 days into our 3-day, 2,345km journey from Astana to our field site, and it was easy to see why Kazakhstan is referred to as Asia’s breadbasket. Spring had finally arrived after an unusually long winter. Tractors were busy burning, ploughing and planting, disappearing into the distance with each pass of the field.

The vast, flat steppe has provided the opportunity for cereal production on a scale unrivalled by the UK’s comparatively small field enclosures. In 2017, Kazakhstan held wheat stocks of 12MMT (million metric tonnes), making UK’s 1.4MMT seem like a drop in the ocean by comparison. Kazakhstan exports wheat globally and is a key player in global food security. Grain elevators capable of storing more than 100,000 tonnes of grain dominate the skyline of every major town and soon became a familiar feature of the landscape to us.

|

| Image credit: Hannah Vineer |

Our journey was punctuated every 6 hours or so by stops at restaurants that seemed to appear out of nowhere. Each one was as unique as the last, their bright colours a reflection of the cheerful nature of the Kazakh people. The popular Tabletkas parked outside reminded me of VW Transporters, and the friendly locals reminded me of my Welsh roots, where strangers greet you on the street.

|

| Image credit: Hannah Vineer |

The restaurants served a range of traditional Kazakh comfort food – meat and milk based meals like borscht, always served with bread, of course. Bread, or нан (pronounced naan) is a staple food here and is said to be the most important part of the dinner table. The menu, written in the Cyrillic alphabet, was indecipherable to me at first and I had to pester the Kazakh and Russian members of our team to help me choose a meal each time. Based on my excited reaction when I finally discovered the image recognition feature of my Google Translate app, you would have thought that I had never seen modern technology before. In truth, I was just relieved to not be such a burden on the rest of team!

|

| Image credit: Hannah Vineer |

Before long we were back on the road and as the hours passed I looked forward to getting to camp and getting started with our work. We planned to visit remote villages, thousands of kilometres off the tourist track, to survey farmers about how they cope with weather extremes such as this year’s particularly harsh winter. But for now, we had run out of time and energy. The sun was setting and we needed to find a place to rest for the night. We headed for the dim twinkling lights of Aktobe, passing a tractor working into the night, illuminating a cloud of dust in its wake. When we eventually found a motel with rooms available, I found it difficult to sleep. I couldn’t wait for the final leg of our journey to our wild camp in the Kazakh steppe.