In what is believed to be the biggest protest in history, in late November 2020 farmers from across India drove 200,000 trolleys and tractors towards Delhi’s borders in a mass protest against agricultural reforms. This was followed a few days later by a general strike involving 250 million people in both urban and rural areas of India as workers joined together to support the farmers.

The strike continues, despite the global public health crisis, which is hitting India harder than any other country in the world. Fear of COVID-19 has not deterred farmers, who have emphatically stated that regardless of whether they contract the virus, the “black laws” will kill them anyway.

The movement first began in the state of Punjab in June 2020, as farmers blocked freight railway lines in protest against these “black laws”, which increase corporate control over all aspects of the food chain from seed to sale. Farmers unions argue that the laws undermine state-controlled prices of key crops, by allowing sales outside of state mandis (markets).

The laws also enable corporations to control what contract farmers grow and how, thus reducing the bargaining power of small farmers. Corporations will be allowed to stockpile key produce and hence speculate with food, which was previously illegal. Finally, the laws provide legal immunity to corporations operating in “good faith”, thereby voiding the ability of citizens to hold agribusiness to account.

Braving tear gas and water cannons, thousands of farmers and their families descended on Delhi and transformed its busy roads into bustling camp cities, with communal “langhar” kitchens.

Undeterred by police violence, farmers fed these aggressors who beat them by day with free food by night. This act of community service not only underscored the peaceful intentions of the protests but also encapsulated one of the key ideas of the movement: “no farmers, no food”.

In the same spirit of solidarity, farmers at Delhi’s borders are responding to the rapidly escalating spread of COVID-19 in the city. They are distributing food packages and essential goods to hospitals, as well as in bus and railway stations for those leaving the capital.

|

| Striking farmers have been supplying food to hospitals and other people in need during the COVID-19 emergency in India. Credit: EPA-EFE/STR. Source. |

Farmers from numerous states, of all castes and religions, are coexisting and growing the protest movement from the soil upwards – literally, turning trenches into vegetable gardens. Many farmers refer to this movement as “andolan” – a revolution – where alliances are being forged between landless farm labourers and smallholder farmers. In a country deeply divided by caste and – increasingly – religion, this coming together around land, soil and food has powerful potential.

Women have also taken leading roles, as they push for recognition as farmers in their own right. They are exploring the intersections of caste oppression, gendered labour and sexual violence in person and in publications such as Karti Dharti – a women-led magazine sharing stories and voices from the movement.

Violent response

Despite the largely peaceful protests, farmers have been met with state repression and violence. At various points water supplies have been cut to the protest sites and internet services blocked. Undeterred, farmers have prepared the camp sites for the scorching summer heat that now envelops them.

Amnesty international has called on the Indian government to “stop escalating crackdown on protesters, farm leaders and journalists”. Eight media workers have been charged with sedition, while 100 people protesters have disappeared. In response, parliaments around the world have issued statements and debates on the right to peaceful protest in India, as well as a free and open press.

|

| Women have been key players in the Indian farmers’ strike. EPA-EFE/Harish Tyagi. Source. |

The heavy-handed government response and intransigence to the key demands of the movement adds grave doubt for farmers who are now being asked to disband protest sites in the interest of public health. It highlights the hypocrisy of being told to go home, while the ruling BJP was holding mass rallies in West Bengal.

The fear is that COVID-19 could derail the momentum of this movement, as with the protests around the Citizen Amendment Act, which were cleared in March 2020 due to enforced lockdown to curb the spread of COVID-19. Farmers repeat that they will leave as soon as the government repeals the laws and protects the minimum support price of key crops.

There has been a groundswell of support from around the globe, from peasant movements, the Indian diaspora community and celebrities – including Rihanna and climate activist Greta Thunberg. This movement is fighting for the principles of democracy on which the Indian state was founded and is part of a civil society movement filling in for the state, which has been found sorely wanting in its response to the calamitous consequences of COVID-19.

The “black laws” are but the latest in a long history of struggle faced by Indian farmers. India’s sprawling fields have been sites of “green revolution” experimentation since the 1960s. This has worsened water scarcity, reduced crop genetic diversity, damaged biodiversity, eroded and depleted soils, all of which has reduced soil fertility.

The financial burden of costly inputs and failing crops has fallen on farmers, leading to spiralling debts and farmer suicides. The impacts of climate change and ecologically destructive farming are primary reasons for this financial duress. However, the movement has yet to deeply address the challenges of transitioning towards socioeconomically just, climate-friendly agriculture.

Peasant movements around the world highlight the importance of collective spaces and knowledge-sharing between small farmers. The campsites in Delhi provide a unique opportunity to link socioeconomic farming struggles to their deep ecological roots. These are indeed difficult discussions, but the kisaan (farmer) movement has provided spaces to challenge caste, religious and gender-based oppression.

The movement’s strength is its broad alliances and solidarity, but it remains unclear whether it will link palpable socioeconomic injustices to environmental injustices and rights. The ecological origins of COVID-19 make these connections ever more pressing the world over.![]()

—————————–

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

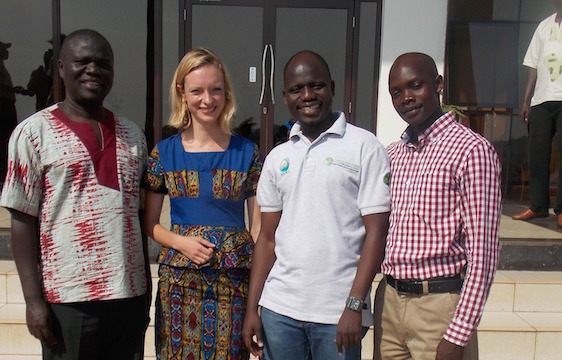

This blog is written by Cabot Institute member Dr Jaskiran Kaur Chohan, at the University of Bristol Vet School. Jaskiran is a political ecologist with an interdisciplinary background in the Social Sciences.

|

| Dr Jaskiran Kaur Chohan |