The Cambridge Global Risk Index for 2019 was presented on 4 December 2018 in the imposing building of Willis Towers Watson in London. The launch event aimed to provide an overview of new and rising risk challenges to allow governments and companies to understand the economic implications of various risks. My interest, as a Knowledge Exchange Fellow working with the (re)insurance sector to better capture the uncertainties embedded in its models, was to find out how the index could help insurance companies to better quantify risks.

The presentation started with the Cambridge Centre for Risk Studies giving an introduction on which major world threats are included in the index, followed by a panel discussion on corporate innovation and ideation.

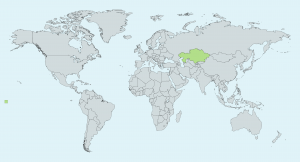

The Cambridge Global Risk Index quantifies the impact future catastrophic events (be they natural or man-made) would have on the world’s economy, by looking at the GDP at risk in the most prominent cities in the world (GDP@Risk). The Index includes 22 threats in five categories: natural disasters and climate; financial, economics and trade; geopolitics and security; human pandemic and plant epidemic; and technology and space.

The GDP@Risk for 2019 for the 279 cities studied, which represents 41% of the global GDP, has been estimated to be $577bn or 1.57% of the GDP of 2019. The GDP@Risk has increased since last year by more than 5%, which was caused by both an increase in GDP globally and a rise in the chances of losses from a cyber attack and other threats to richer economies. Risk is becoming ever more interconnected due to cascading threats, such as natural hazards and climate events triggering power outages, geopolitical tensions triggering cyber attacks sponsored by states, conflicts worsening human epidemics, and trade wars triggering sovereign crises, which in turn caused social unrest.

Nonetheless, the GDP@Risk can be reduced by making cities more resilient, that is improving the ability of a city to be prepared for a shock and to recover from it. For example, if the worst off 100 cities in the world would be as prepared as the top cities, they could reduce their exposure to risk by around 30%, which shows the importance of investing in resilience and recoverability. This is a measure of what the insurance industry calls the “protection gap”, how much could be earned from investments to improve the preparedness and resilience of a city to shocks. How fast a city recovers depends on the ability to access capital, to reconstruct and repair factories, houses and infrastructure, to restore consumers’ confidence and to reduce the length of business interruption.

Natural catastrophe and climate

After a 2017 with the second highest losses due to natural disasters, 2018 saw several record-breaking natural catastrophes as well. This year we have experienced events from magnitude 7.5 earthquakes and tsunami in Indonesia, which caused more then 3000 deaths, to the second highest number of tropical cyclones active in a month, from Typhoon Mangkhut in the Philippines, to Japan’s strongest storm in the last two decades. Hurricanes have beaten records too, with hurricane Florence in North Carolina becoming the 2nd wettest hurricane on record, which caused $10 bn losses, and hurricane Michael in Florida reaching the greatest wind speeds ever recorded, which caused $15 bn losses.

Floods in 2018 caused heavy death tolls in Japan and south India, with 225 and 500 fatalities respectively, the former showing the weakness of an ageing city infrastructure, while the latter raising criticism on poor forecasting and management of water resources. Droughts raged in South Africa, Australia, Argentina, Uruguay and Italy reducing harvests, while wildfires in California were the largest on record, which caused $20 bn losses. Extreme events have made it to weather events too, with extreme heatwaves, as the hottest summer in the UK, comparable to the one of 1976, and the heatwave in Japan which hospitalised 35,000 people, as well as with extreme freeze, as the “Beast from the East” in the UK which caused losses estimated at $1 billion per day.

Extreme events are becoming ever more frequent due to climate change, with the next few years expected to be anomalously warm, even on top of the regular climate change. This hints that the rising trend in losses due to natural catastrophe and climate is not due to stop.

|

| Devastation from the cyclone in Tonga, 2018. |

Finance, economics and trade

Market crash is the number one threat for 2019, which could cause more than $100 billion in losses. Nonetheless global financial stability is improving due to increased regulation, but risk appetite has increased as well due to positive growth prospects and low interest rates, which increases financial vulnerabilities. Trade disputes between the US and China and the US and Europe are disrupting the global supply chains. The proportion of GDP@Risk has increased in Italy due to policy uncertainty and increased sovereign risks, while in countries such as Greece, Cyprus and Portugal sovereign debt risks have decreased following restructuring of their debt and country level credit rating upgrades.

Geopolitics and security

The risk from geopolitics and security worldwide has remained relatively similar compared to last year, with roughly the same countries being in conflict as in 2017. Iran’s proxy presence remains in conflicts in Yemen, Iraq, Israel, Syria and Lebanon, while social unrest has increased risk in Yemen, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Argentina, Iraq and South Africa. The conflict in Yemen has caused the world’s worst humanitarian crises in 2018, with more than 2 million displaced, with food shortages and malnutrition causing cholera outbreak. The total expected loss from this category is similar to the one from financial, economic and trade risk.

Technology and space

Technology and space is the category with the lowest expected GDP at risk. Nevertheless, the risk has increased over recent years, with cyber attacks becoming ever more frequent due to the internationalisation of cyber threat, the increasing size and cost of data breaches, the continued disruption from DDoS attacks, the threat to critical infrastructure, and its continuous evolution and sophistication. Cyber attacks have climbed one level in the ranking this year, assuring the 6th overall position. In 2017 the WannaCry ransomware attacks affected 300,000 computers across 150 countries disrupting critical city infrastructure, such as healthcare, railways, banks, telecoms and energy companies, while NotPetya produced quarterly losses of $300 million for various companies. The standstill faced by the city of Atlanta when all its computers were locked due to a ransomware attack in March caused £2.6 million to be spent, and another $9.5 million are expected. This attack highlighted the breath of potential disruption, with energy, nuclear, water, aviation and manufacturing infrastructure at risk. Moreover 66% of companies are estimated to have experienced a supply chain attack, costing on average $1.1 million per attack. In response to these threats, countries are increasing their spending on cyber offensive capability, with the UK spending hundreds of millions of pounds. Power outage, nuclear accident and solar storm are not at the top of the threats ranking globally, but solar storms could cause over $4bn of GDP@Risk in North American cities, due to their position in northern latitudes, leaving 20-40 million people without power.

Health and humanity

The greatest threat to humanity according to the UN is anti-microbial resistance, with areas in the world already developing strains of malaria and tuberculosis resistant to all available medicines. It is expected that over the next 35 years 300 million people will die prematurely due to drug resistance, decreasing the world’s GDP between 2 and 3.5% in 2050. Major epidemics have remained largely constrained in the same areas as last year, and are fuelled by climate and geopolitical crises which aggravates hygiene and public health, such as the Yemen and Somalia cholera outbreaks. Plant epidemics have not increased, with the ongoing problems of Panama disease in bananas, coffee and wheat rust, and the xylella fastidiosa still affecting olive plants in southern Europe.

Corporate innovation and ideation discussion

The panel discussed the importance of the Cambridge Global Risk Index to prepare companies for future threats. For example, for insurance companies including the index in their management of risk would allow them to be better prepared and more profitable. I found the words of Francine Stevens, director of Innovation at Hiscox, particularly inspiring. She talked about how the sheer volume of research produced is often too large to be digested by practitioners, and how workshops might help to bring people with similar interests together to pull out what are the most exciting topics and challenges to work on. As a Knowledge Exchange Fellow myself, this strikes a familiar chord, as it is my job to transfer research to the insurance sector and I have first-hand experience on the importance of adopting a common language and identifying how industry uptakes new research and methods.

Francine has also talked about the importance of collaboration between companies, a particularly sensitive topic in the highly competitive insurance sector. This topic emerged also at the insurance conference held by the Oasis Loss Modelling Framework in September, where the discussion touched on how non-competitive collaborations could bring the sector forward by avoiding duplication. Francine’s final drop of wisdom was about the importance of diversity to drive innovation, and how having a group of smart people with diverse backgrounds often delivers better results than a group of high-achievers with the same background. And this again sounded very familiar!

————————————-

This blog is written by Cabot Institute member Dr Valentina Noacco, a NERC Knowledge Exchange Fellow and a Senior Research Associate at the University of Bristol Department of Civil Engineering. Her research looks at improving the understanding and consideration of uncertainty in the (re)insurance industry. This blog reports material with the consent of the Cambridge Centre for Risk Studies and is available online at https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/faculty-research/centres/risk/news-events/events/2018/cambridge-global-risk-index-2019-launch-event/.

|

| Dr Valentina Noacco |