Our planet and the people who live upon it face profound challenges in the coming century. As our population, economies and aspirations grow we consume increasing amounts of precious and finite resource. The side effects and waste products of this consumption also have profoundly negative impacts on our environment and climate, which in a vicious circle will make it even harder to support our food, energy and water needs.

In order to live on this planet, we must bridge the gap between wasteful lifestyles based on limited resources to efficient lifestyles based on renewable ones. Nowhere is that more apparent than in our consumption of fossil fuels. Much of our prosperity over the past two centuries has derived from the exploitation of these geological gifts, but those gifts have and are causing climate change with potentially devastating consequences. These are likely to include more extreme weather, loss of marine ecosystems and droughts; in turn, these could cause famine, refugee crises and conflict.

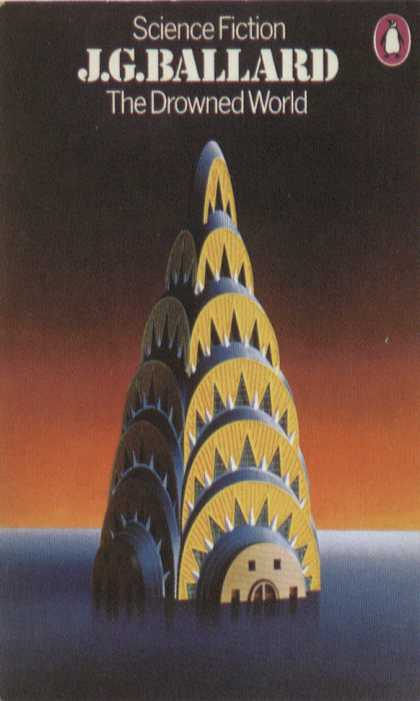

These climatic and environmental impacts will be felt locally in the European Green Capital as well as globally. We live in an interconnected world, such that drought in North America will raise the price of our food. The floods of last winter could have been a warning of life in a hotter and wetter world. Many of us in the South West live only a few metres above current sea level.

In my own work with Cabot Institute colleagues, I have investigated not just how Earth’s climate might change but how it has changed in the past. This shows that our climate forecasts are generally right when it comes to the temperature response to greenhouse gases, although perhaps they underestimate how much the poles will warm. More concerning, Earth history reveals how complex our planet is; with dramatic biological and physical responses to past global warming events. During one such event 55 million years ago, rapid warming transformed our planet’s vegetation and water cycle: rivers in Spain that had carried fine grained silts suddenly carried boulders. And that ‘rapid’ warming event occurred over thousands to tens of thousands of years not two hundred a reminder of the unprecedented character of our current climate change experiment.

| Flooding in Whiteladies Road, Bristol. Credit: Jim Freer |

Consequently, despite our best understanding of some factors, climate change will make our world a more uncertain place, whether that be uncertainty in future rainfall, the frequency of hurricanes or the timing of sea level rise. This uncertainty is particularly problematic because it makes it so much harder for industry or nations to plan and thrive. How do we ensure a robust and continuous food supply if we are unsure if the planet’s bread baskets will become wetter or dryer? Or if we are unsure how our fisheries will respond to warmer, more acidic, more silt-choked oceans?

Underlying this uncertainty is a deep ethical question about who will bear the risk and the inequality issues hidden within our choices. Most of us recognise that we are consuming the resources and polluting the environment of our children. But the inequity is deeper than that it is not all of our children who will suffer but the children of the poorest and the most vulnerable. Those whose homes are vulnerable to floods, who lack the resources to move or the political capacity to emigrate, who can barely afford nutritious food now, whose water supplies are already stretched and contaminated.

Bristol in 2015 will not bridge the gap by despairing at these challenges, but we can lead in acknowledging them. We can lead in showing how to avoid the worst uncertainty and taking responsibility for the consequences of where our efforts fall short. Most importantly, we can lead towards not just radical resiliency but inclusive resiliency.

This blog is by Prof Rich Pancost, Director of the Cabot Institute at the University of Bristol.

|

| Prof Rich Pancost |