Cabot Institute Director Professor Rich Pancost will be attending COP21 in Paris as part of the Bristol city-wide team, including the Mayor of Bristol, representatives from Bristol City Council and the Bristol Green Capital Partnership. He and others Cabot Institute members will be writing blogs during COP21, reflecting on what is happening in Paris, especially in the Paris and Bristol co-hosted Cities and Regions Pavilion, and also on the conclusion to Bristol’s year as the European Green Capital. Follow #UoBGreen and #COP21 for live updates from the University of Bristol. All blogs in the series are linked to at the bottom of this blog.

—————————–

|

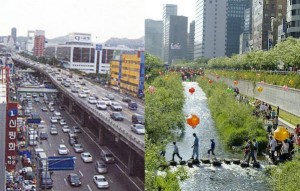

| Scene from COP21 |

The first several days of COP21 have seen a flurry of announcements, propositions and commitments. Just within the Bristol/Paris/ICLEI tent, numerous new ideas have emerged as city after city has stepped forward and proposed its Transformative Action Plans. Despite the diversity of propositions, the key themes are emerging: Leaders must be brave and adventurous; we must all work together in new and innovative partnerships built on trust; and engagement with the next generation is crucial.

These are not terribly surprising!

The challenge for leaders to be brave was the key message from the Mayors of the past and future European Green Capitals. Speaking after the panel, Katarina Luhr, Vice Mayor from Stockholm, said:

“My message to the politicians negotiating at COP21 is to look to the future and be brave.”

I could not agree with this more. Going ahead, as we face increasingly difficult challenges, navigate contentious compromise, or try something new and unknown, this bravery will become even more important… and more complicated. Populations will have to empower leaders to be bold and leaders will have to earn that right by building trust.

The Cabot Institute has been discussing this with our colleagues and partners (including the University’s new Brigstowe Institute) over the past year – and we are certainly not alone in this. We will report more on these issues in the coming months, but one emerging theme is how trust can be built through partnership. (See my blogs on the importance of University of Bristol partnerships here and here).

Few challenges, whether it be tackling climate change, resolving inequality or building a sustainable health service as our population ages, can be solved by a single agent acting alone. Appropriately, George Ferguson and Cllr Daniella Radice, Assistant Mayor for Neighbourhoods, including Environment, emphasised partnership as they opened the discussion on the first day of the Cities and Regions Pavilion. And of course, the Pavilion itself is the product of partnership between Bristol, Paris and ICLEI, itself a partnership of >1000 local and sub-national organisations.

Partnership is necessary. Diverse contributors with diverse perspectives and expertise must work together to solve the climate change crisis.

And partnership is hard. It requires a deep and long-term commitment and a willingness to share, compromise and trust. It is at the heart of the University of Bristol’s ambitions , including how we work with our city, but we also recognise that that requires long term commitment. We’re trying but we’re not going to pretend we have it cracked.

One great example of successful partnership is Bristol is Open, a joint venture between the University of Bristol and Bristol City Council but designed in a way to be open to a variety of new partners from business and civil society. BIO is a combination of state-of-the-art, publicly owned fibre-optic infrastructure, environmental sensors, 5G wireless technology, the university’s high performance computing and programmable city models. It could enable a new type of smart city in which traffic, flood, emergency, and energy services are managed in real time to achieve efficiency, sustainability and resilience.

But that is the future of BIO. What it is now is a city-wide laboratory that will be open for experimentation and innovation. It is an invitation to partnership. And one of the first steps in that invitation was the 18 November Festival of the Future City launch of the Data Dome, the UK’s first 3D, interactive dome for data visualisation at At-Bristol. The purpose and value of the smart, programmable city can be difficult to grasp – it was for me! The Data Dome, similar to the Playable City initiative, is a way to share and explore the potential of this technology while learning about our city. [And the Bristol Brain, one of Bristol’s Transformative Action Plan propositions discussed on Tuesday, will also be central to this.]

Another truly exciting arena for partnership is the recently announced UKCRIC programme, led in Bristol by Professor Colin Taylor, also the theme leader for the Cabot Institute’s Future cities and communities research theme. We will be discussing this much more in the future, especially as we launch the Collaboratory component of it, which will bring investment to the centre of Bristol to support even further collaboration and innovation.

Of course, one of the most exciting and successful examples of partnership that I have seen in Bristol or any other city is the Bristol Green Capital Partnership (BGCP), which was key to winning the European Green Capital award and remains dedicated to building momentum for climate action. Gary Topp, Development Director for the Partnership and Honorary Fellow in the University of Bristol, was part of the team showcasing Bristol’s ambition on Tuesday in Paris, where he outlined its work involving over 850 organisations committed to creating ‘a low carbon city with a high quality of life for all’. For other Green Capitals, creating a partnership was a major success; we started with one. And it is now the largest of its kind in the world.

One of the things I am most proud of in the Cabot Institute has been our support of and work with the BGCP (which predates my current role by several years). Our Manager Philippa Bayley was the directly elected co-Director of the Partnership in 2014 (with the amazing Liz Zeidler of Happy City, about which I could write a whole extra blog!), and we have several ongoing projects. The Partnership is now gearing up to be a central and sustainable part of the 2015 legacy, serving as a uniting, empowering and vocal participant in the future of our city. On 26 November 2015, working with Crowdfunder UK, they launched their most recent initiative, the Better Bristol campaign to find new ways to support exciting and potentially transformative projects. The largest such partnership in the world, the BGCP will play an essential role in ensuring that Bristol continues to be a place where grass roots projects thrive.

Mayor George Ferguson emphasised this principle in his concluding comments, noting that while targets and technology were important, the European Green Capital award was about people and partnerships among civil society, with schools, businesses and other cities. “Recognising that we cannot work in isolation,” he added, “is absolutely vital. We need to shape our cities in partnership, finding common links to suit everybody, provide confidence to deal with the unknown and take control of our destinies.”

A final example of this Partnership came later in the day, when our former Cabot Institute colleague Professor Andy Gouldson (now at Leeds) shared his research in investment in a sustainable future for Bristol. It revealed that over the next decade, such investment could save Bristol up to £300 million on its energy bills and create up to 10,000 jobs. The report ‘The Economics of Low Carbon Cities: a Mini-Stern Review for the City of Bristol, was commissioned by the Cabot Institute and funded by the University, and uses a robust model to assess the costs and benefits of low carbon projects to accelerate Bristol’s progress. A similar initiative, STEEP, involving Cabot Institute academic Mike Yearworth, showed how Systems approaches could also bring about city-scale energy efficiencies. Both are underpinning Bristol’s consultation around its Climate and Energy Security.

So enough patting ourselves on the back. These are some nice emerging success stories. But we can do better.

Partnerships work best when everyone benefits, but we must put more effort into building deeper and more powerful trust so that partnerships create room for compromise. Or even temporary sacrifice. Perhaps more importantly, we recognise that many people do not feel included in these ‘partnerships’. This requires more thought and reflection than a few paragraphs in a single blog. Therefore, allow me to simply note this challenge and trust me to return to it; and I will finish by focussing on one of our most important partners.

The youth of our city and our planet

As an educational institution, we must make a strong commitment to prepare the next generation. Our offer should be imaginative, distinctive and innovative – and it should prepare our students to be global citizens, committed to a sustainable and just future, and inspired to be creative and enterprising. These concepts are intrinsic to our ongoing Strategic Review, being led by our new Vice-Chancellor Hugh Brady.

They are also being embedded at an earlier age through one of Bristol 2015’s flagship successes. On 24 Nov, the city launched the Sustainable Learning programme, shared with thousands of Bristol children and underpinned by the award-winning Shaun the Sheep app.

We must prepare the next generation to live in a more volatile and unpredictable world. The University of Bristol is committed to that.

We must also prepare the world for them. This is not about solving all the problems for them; nor is it just about giving them the education to solve problems. It is also about creating the social, economic, legal and infrastructure framework that leaves room for them and their ideas and their creativity. I think all policies, regulations and treaties (or their removal) should be tested against a central rule: does this create options for future generations or take them away. The next generation must inherit a world where creativity and innovation are allowed to thrive. The Cabot Institute is committed to that.

But we must be equally committed to working with them now.

|

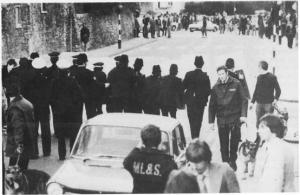

| Young people at the Bristol Climate March this year. |

George Ferguson emphasised this in Paris: “We all recognised the importance of putting our young people first and foremost; involving them in how we plan for their future… those young people often come up with ideas and solutions that are better than those of their older counterparts. Building cities for the future cannot just be for youth, it has to be with them”.

I have written (and tweeted) about how deeply impressed I am by our Youth Council and our Youth Mayors, several of whom were just nominated by RIFE Magazine as 24 Influential People under 24. They are brave! And smart and informed and passionate. They have ambition for themselves and ambition to make the world a better place and we would be fools to simply wait for them to become future leaders. They have much to offer now.

But that involves more than just inviting them to the meeting; it means letting them set the agenda.

Are we brave enough to do that?

This blog is part of a COP21 daily report series. View other blogs in the series below: