Lewis Collard/Wikipedia

Winter frost fairs were common on the frozen River Thames between the 17th and 19th centuries, but they’ve become unimaginable in our lifetime. Over decades and centuries, natural variability in the climate has plunged the UK into sub-zero temperatures from time to time. But global warming is tipping the odds away from the weather we once knew.

These days, people in the UK have become accustomed to much warmer, wetter winters. In fact, winter is warming faster than any other season. This is bad news for those holding out for a white Christmas – the Met Office reports that only four Christmases in over five decades recorded snow at more than 40% of UK weather stations.

Thomas Wyke/Wikipedia

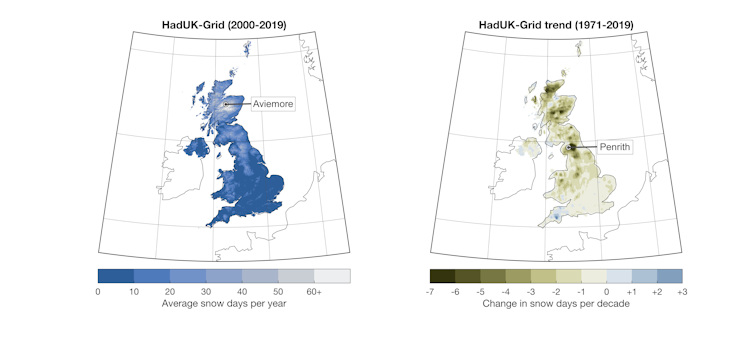

Christmas is a magical day for many, but meteorologically, it’s no different from other winter periods, when snow and ice are also becoming less common. The Met Office definition of a snow day at a given location in the UK is when snow lies on at least 50% of the ground at 9am. Currently, the Cairngorms around Aviemore receive over 70 snow-lying days per year – the most in the UK.

This amount is smaller than in previous decades though. Met Office data shows that, since 1979, the number of snow-lying days has generally decreased by up to five days per decade, and up to ten days per decade in the North Pennines, near Penrith. Around a fifth of the total area of the UK has experienced a significant drop in the prevalence of days with snow lying on the ground.

Met Office, Author provided

What causes snow days?

Snow days are often the result of a meandering jet stream, the fast-flowing current of air that’s between 9km and 16km above the Earth’s surface. The jet stream normally transports temperate weather from the Atlantic across the UK, but if it’s displaced southwards, it allows persistent high pressure systems of colder air from the north and east, originating in the Arctic or over the Eurasian continent, known as blocking high pressures, to settle over the UK for extended periods.

A number of atmospheric processes can cause the jet stream to meander, but perhaps the most dramatic is when the stratospheric polar vortex, a huge rotating air mass in the middle atmosphere, breaks down. This disruption causes the jet stream to weaken, leading to events such as the infamous 2018 Beast from the East, which brought widespread snowfall to the UK.

The winter of 2018 was not unique in this sense – 2009-2010 and 2013 both brought snowfall because of these dynamic “beasts”. So why is there still a decline in winter snow days in the UK?

The snows of yesteryear

There’s no strong evidence for a long-term trend in polar vortex disruptions, or other atmospheric processes that influence the jet stream. So the fact that people in the UK have fewer snow days to enjoy each year than they did in the past can’t be blamed on the invisible twists and turns above their heads.

But as the concentration of CO₂ in the atmosphere climbs, disruptions that do occur sit on top of increasing background temperatures, reducing the likelihood of the cold spells that bring widespread snowfall. Just as natural climate trends have lowered the severity of winters since the days of the frost fairs, man-made climate change will increasingly keep the UK’s average temperature above zero.

A heavy covering of snow can transform the country and our perception of it. Snow days, with the closures of schools and workplaces that they bring, evoke fond memories and bring out the child in many as hillslopes and parks become sledging highways. More tangibly, in Scotland, the snowsports industry is estimated to be worth over £30 million a year.

But wintry weather can be dangerous too. The cold affects our health, exacerbating heart and lung conditions and the spread of infectious diseases. In extreme cases, heavy snowfall can cause widespread livestock deaths, which happened in Northern Ireland in 2013. The inevitable disruption to travel and businesses can cause economic damage running into billions of pounds, with sectors like the construction industry halted entirely.

While the falling chances of a white Christmas might disappoint many, the current trajectory of less and less snow will at least come as a relief to some.![]()

————————-

This blog is written by Cabot Institute members Dr Alan Thomas Kennedy-Asser, Research Associate in Climate Science, University of Bristol; Dr Dann Mitchell, Met Office Co-Chair in Climate Hazards, University of Bristol, and Dr Eunice Lo, Research Associate in Climate Science, University of Bristol.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Dann Mitchell |

|

| Alan Kennedy-Asser |

|

| Eunice Lo |