Three Cabot Institute researchers provide their own insights on the highly publicised news story about the extent of melting observed on the Greenland Ice Sheet.

Chris Vernon, Ph.D student in the Bristol Glaciology Centre, studying the mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet

Last week NASA released new images of the Greenland ice sheet generated from satellite data showing that between the 8th and 12th of July 2012 the area of the ice sheet’s surface that was melting had increased from about 40 percent to an estimated 97 percent. On average during the summer approximately half of the ice sheet experiences such surface melting and this expansion of the melt area to include the highest altitude and coldest regions was described as “unprecedented” by the scientists at NASA. Such widespread melting has not been seen before during the past 34 years of satellite observations and melting at Summit Station, near the highest point on the ice sheet, has not occurred since 1889 based on ice core records.

The Greenland ice sheet gains mass from rain and snowfall and loses mass by solid ice discharge to the ocean (iceberg calving) and runoff of surface melt water. During the period 1961-1990 these processes are thought to have been in balance with the ice sheet’s mass stable (Rignot et al., 2008). During the last two decades, however, both ice discharge and liquid runoff have increased resulting in the ice sheet losing mass over this period at an accelerating rate (Velicogna, 2009, Rignot et al., 2011). Changes to these two processes have contributed approximately equally to recent mass loss (van den Broeke et al., 2009). Whilst these NASA images do not provide data about how much snow and ice have melted or the direct effect on mass balance, they do indicate a significantly larger area of the ice sheet has been melting.

While this melting is an extreme weather event, associated with a series of unusually warm fronts passing over Greenland this summer, new research on the ice sheet’s albedo from Jason Box, a researcher with Ohio State University’s Byrd Polar Research Center, shows summer albedo has been decreasing over the last decade. This reduced reflectivity, particularly at high elevations, is associated with warming related feedbacks and means more energy is absorbed at the surface for melting leading Box to suggest earlier this year that it is reasonable to expect 100% melt extent within another decade of warming (Box et al., 2012). His latest albedo data are available here: http://bprc.osu.edu/wiki/Latest_Greenland_ice_sheet_albedo.

References (some behind paywall)

BOX, J. E., FETTWEIS, X., STROEVE, J. C., TEDESCO, M., HALL, D. K. & STEFFEN, K. 2012. Greenland ice sheet albedo feedback: thermodynamics and atmospheric drivers. The Cryosphere Discuss, 6, 593-634.

RIGNOT, E., BOX, J. E., BURGESS, E. & HANNA, E. 2008. Mass balance of the Greenland ice sheet from 1958 to 2007. Geophysical Research Letters, 35.

RIGNOT, E., VELICOGNA, I., VAN DEN BROEKE, M. R., MONAGHAN, A. & LENAERTS, J. 2011. Acceleration of the contribution of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets to sea level rise. Geophysical Research Letters, 38.

VAN DEN BROEKE, M., BAMBER, J., ETTEMA, J., RIGNOT, E., SCHRAMA, E., VAN DE BERG, W. J., VAN MEIJGAARD, E., VELICOGNA, I. & WOUTERS, B. 2009. Partitioning Recent Greenland Mass Loss. Science, 326, 984-986.

VELICOGNA, I. 2009. Increasing rates of ice mass loss from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets revealed by GRACE. Geophysical Research Letters, 36.

Liz Stephens, Research Assistant in flood risk and co-author of article: ‘Communicating probabilistic information from climate model ensembles-lessons from numerical weather prediction’ soon to be published in WIRES Climate Change

The story of the unprecedented extent of melting of the Greenland ice sheet no doubt forms an important discussion point amongst scientists and those concerned about future climate change in the Arctic. However, for me it demonstrated the problems of clumsy communication; causing confusion that led some to think that the entire ice sheet had melted, and accusations of sensationalism from climate change sceptics (see http://sfy.co/a1AS for examples).

My main grievance is in the use of colour in the images. This may be the standard colour bar used by the NASA scientists, but it is too emotive for those not used to what is being referred to. At first glance the white area suggests ‘this is ice’, and the red, ‘we should be really scared that this is no longer white’. In my opinion the colour white should not be used because it is evocative of what is ice rather than what is freezing ice, and so more neutral colours should be used to distinguish areas of melting from areas of freezing ice.

Additionally, I think that some of the language used is problematic; scientists need to be careful not to assume that people understand what is meant by the terms ‘ice sheet’, ‘area’, ‘surface’ etc., so that people don’t think that the entire volume of the ice sheet has disappeared. Further, the subheading of the Guardian article – 97% surface melt over four days – is misleading, because the images refer to the area of the ice sheet that is undergoing melting and not the rate of melting itself, and so is not a direct indication of any volume of ice lost.

I also don’t like some of the phrasing used, particularly, ‘had thawed’. This is perhaps misleading, because if 97% of the ice sheet surface ‘had thawed’, then perhaps some might think that only 3% of the ice sheet surface would be left. I would probably go for an image caption of:

“The area of the Greenland ice sheet surface that was melting on July 8, left, compared to July 12th on the right.”

Subtle changes to the language can make it clear that this is an unusual weather event that could be indicative of climate change, rather than the ice sheet starting to disappear for good.

Jon Hawkings, Ph.D student in the Bristol Glaciology Centre, studies the chemistry of glacial meltwaters

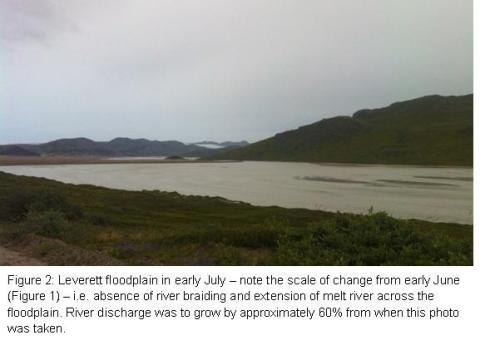

During the course of my stay at the University of Bristol-led field site near Leverett glacier in south-west Greenland, I witnessed the start of what has since been identified as one of the most significant Greenland melt years over the past century. Over that time Leverett glacier’s subglacial drainage river, fed by the melting ice sheet surface together with stored meltwater from the bed, had altered from a small stream to a raging torrent. Although this is usual for a glacial river during a melt season in Greenland, the scale of change was unprecedented. Temperatures around camp far exceeded my expectations. I packed expedition gear expecting Arctic summer temperatures of around 10°C – a little higher than I had previously experienced in the northerly island archipelago of Svalbard. What I experienced were temperatures sometimes reaching 20°C. In our camp mess tent where we cooked and ate our meals the temperature would sometimes exceed 30°C – shorts and t-shirt weather – were it not for the thousands of mosquitoes that were thriving in the warmer weather. In June I often found myself processing samples in the science tent with beads of sweat on my brow.

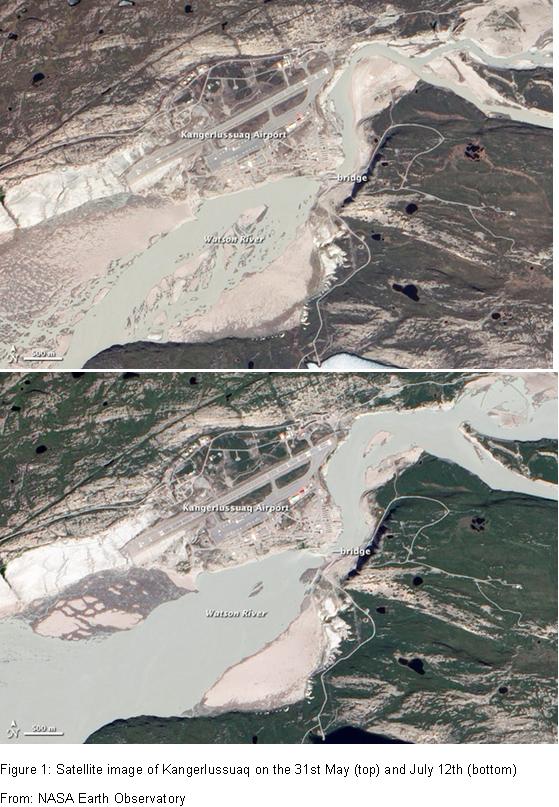

When the discharge of the river exiting the margin of Leverett glacier hit around 500 m3/s in late June (over six times that of the average River Thames discharge when flowing through London), it was evident to all of the camp that the 2012 melt season was going to be much larger than in previous years. Over the period that Leverett catchment has been studied (2009-), river discharge usually reaches a high of 405 m3/s, and that was in early August – more than a month after this high (and therefore after a month’s more melt). At that time a bridge crossing the glacial meltwater river in the nearest town, Kangerlussuaq, approximately 25 km downstream (Watson River, fed by Leverett glacier and two other large glaciers in the area), had to be closed as the amount of water deemed it unsafe. I’ve recently been informed that discharge of Leverett river has subsequently hit more than 800 m3/s since I left camp – nearly twice that of the previous high. At the same time Watson River discharge at Kangerlussuaq was nearly double its previous high (3500 m3/s – more than the average discharge of the Nile), and in dramatic fashion has washed away the same bridge that was closed in 2010 (see http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/picture/2012/jul/27/glaciers-flooding?newsfeed=true# and http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/jul/25/greenland-glacier-bridge-destroyed-video?newsfeed=true). Although a trend for higher melt season discharge has been observed, locals and scientists in the Kangerlussuaq area have all been taken aback by the magnitude of change experienced this year (http://www.ouramazingplanet.com/3254-greenland-flooding.html).

As this was my first field season in Greenland it was difficult for me to grasp the scale of change from previous years. Ben Linhoff, an isoptope geochemist from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts, USA, has been in camp during the 2011 and 2012 melt seasons, and was surprised by the difference in temperature and river size between the two years. He has documented the scale of change on his Scientific American blog (http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/expeditions/tag/following-the-ice/), and in a short video with Andrew Tedstone of the University of Edinburgh (http://www.whoi.edu/page.do?pid=80757&cl=82073&tid=5122). Ben comments that air temperatures in camp are substantially warmer than in 2011 and that glacial moraine deposited by Leverett glacial hundreds of years ago (possibly during the Little Ice Age) was being eroded by Leverett river – likely for the first time in decades. Dave Chandler, a University of Bristol researcher, camped within the ice sheet interior, 40km from the margin, has also been surprised by the warm temperatures. During the 2011 melt season he found that the temperature on the ice very rarely exceeded freezing at night. In contrast, the temperature has stayed above freezing throughout most of June and July at a similar point on the ice this year. Higher temperatures and the lack of freezing conditions on the ice sheet interior mean that more glacial ice has melted on the surface. This water is then thought to be routed to the bed through conduits know as moulins. At the bed the meltwater joins a large subglacial channel that flows under the ice and exits the glacier via a portal such as that which exists on Leverett glacier. The discharge of these subglacial rivers is thus indicative of the amount of ice melt.

![]()