We’ve got lots of media trained climate change experts. If you need an expert for an interview, here is a list of Caboteers you can approach. All media enquiries should be made via Victoria Tagg, our dedicated Media and PR Manager at the University of Bristol. Email victoria.tagg@bristol.ac.uk or call +44 (0)117 428 2489.

Climate change / climate emergency / climate science / climate-induced disasters

Professor Daniela Schmidt – expert in the causes and effects of climate change on marine systems. Dani is also a Lead Author on the IPCC reports.

Dr Vikki Thompson – expert on climate extremes, particularly heat extremes. Follow on Twitter @ClimateVikki

Dr Katerina Michalides – expert in drylands, drought and desertification and helping East African rural communities to adapt to droughts and future climate change. Follow on Twitter @_kmichaelides.

Professor Dann Mitchell – expert in how climate change alters the atmospheric circulation, extreme events, and impacts on human health. Dann is also a Met Office Chair. Follow on Twitter @ClimateDann.

Professor Dan Lunt – expert on past climate change, with a focus on understanding how and why climate has changed in the past and what we can learn about the future from the past. Dan is also a Lead Author on IPCC AR6. Follow on Twitter @ClimateSamwell.

Professor Jonathan Bamber – expert on the impact of melting land ice on sea level rise (SLR) and the response of the ocean to changes in freshwater forcing. Follow on Twitter @jlbamber

Professor Paul Bates CBE – expert in the science of flooding, risk and reducing threats to life and economic losses worldwide. Follow on Twitter @paul_d_bates

Professor Tony Payne – expert in the effects of climate change on earth systems and glaciers.

Dr Matt Palmer – expert in sea level and ocean heat content research at the Met Office Hadley Centre and University of Bristol. Follow on Twitter @mpclimate.

Net Zero / Energy / Renewables

Professor Valeska Ting – Engineer and expert in net zero, low carbon technologies, low carbon energy and flying. Also an accomplished STEM communicator, is an BAME Expert Voice for the BBC Academy. Follow on Twitter @ProfValeskaTing.

Professor Philip Taylor – Expert in net zero, energy systems, energy storage, utilities, electric power distribution. Also Pro-Vice Chancellor at the University of Bristol. Follow on Twitter @rolyatlihp.

Dr Colin Nolden – expert in sustainable energy policy, regulation and business models and interactions with secondary markets such as carbon markets and other sectors such as mobility. Colin will be at COP27. Colin will be in attendance in the Blue Zone at COP27.

Professor Charl Faul – expert in novel functional materials for sustainable energy applications e.g. in CO2 capture and conversion and energy storage devices. Follow on Twitter @Charl_FJ_Faul.

Climate finance

Dr Rachel James – Expert in climate finance, damage, loss and decision making. Also has expertise in African climate systems and contemporary and future climate change. Follow on Twitter @_RachelJames. Rachel will be in attendance in the Blue Zone at COP27.

Climate justice

Dr Alix Dietzel – climate justice and climate policy expert. Focusing on the global and local scale and interested in how just the response to climate change is and how we can ensure a just transition. Alix will be at COP27. Follow on Twitter @alixdietzel. Alix will be in attendance in the Blue Zone at COP27.

Dr Ed Atkins – expert on environmental and energy policy, politics and governance and how they must be equitable and inclusive. Also interested in local politics of climate change policies and energy generation and consumption. Follow on Twitter @edatkins_.

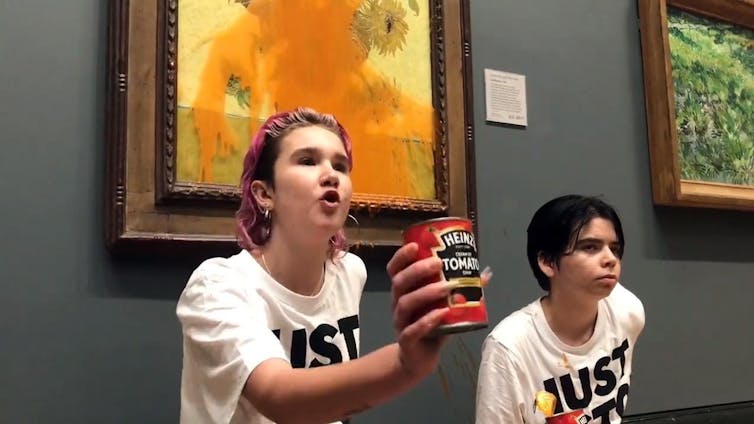

Climate activism / Extinction Rebellion

Air pollution / Greenhouse gases

Dr Aoife Grant – expert in greenhouse gases and methane. Set up a monitoring station at Glasgow for COP26 to record emissions.

Professor Matt Rigby – expert on sources and sinks of greenhouse gases and ozone depleting substances. Follow on Twitter @TheOtherMRigby.

Land, nature and food

Climate change and infrastructure

Dr Maria Pregnolato – expert on effects of climate change and flooding on infrastructure. Follow on Twitter @MariaPregnolat1.