Nearly 17% of the world’s croplands are contaminated with “heavy metals”, according to a new study in Science. These contaminants – arsenic, cadmium, lead, and others – may be invisible to the eye, but they threaten food safety and human health.

Heavy metals and metalloids are elements that originate from either natural or human-made sources. They’re called “heavy” because they’re physically dense and their weight is high at an atomic scale.

Heavy metals do not break down. They remain in soils for decades, where crops can absorb them and enter the food chain. Over time, they accumulate in the body, causing chronic diseases that may take years to appear. This is not a problem for the distant future; it’s already affecting food grown today.

Some heavy metals, such as zinc and copper, are essential micronutrients in trace amounts. Others – including arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead – are toxic even at low concentrations.

Some are left behind by natural geology, others by decades of industrial and agricultural activities. They settle into soils through mining, factory emissions, fertilisers or contaminated water.

When crops grow, they draw nutrients from the soil and water – and sometimes, these contaminants too. Rice, for instance, is known for taking up arsenic from flooded paddies. Leafy greens can accumulate cadmium. These metals do not change the taste or colour of food. But they change what it does inside the body.

The quiet health crisis beneath our crops

Long-term exposure to arsenic, cadmium, or lead has been linked to cancer, kidney damage, osteoporosis, and developmental disorders in children. In regions where local diets rely heavily on a single staple crop like rice or wheat, the risks multiply.

The Science study, led by Chinese scientist Deyi Hou and his colleagues, is one of the most comprehensive mapping efforts. By combining recent advances in machine learning with an expansive dataset of 796,084 soil concentrations from 1,493 studies, the authors systematically assessed global soil pollution for seven toxic metals: arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, chromium, copper, nickel, and lead.

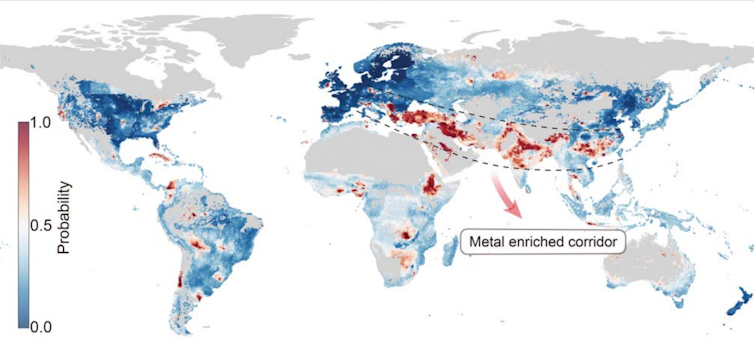

The study found that cadmium in agricultural soil frequently exceeded the threshold, particularly in the areas shaded in red in this map:

Hou et al / Science

The authors also describe a “metal-enriched corridor” stretching from southern Europe through the Middle East and into south Asia. These are areas where agricultural productivity overlaps with a history of mining, industrial activity and limited regulation.

How science is reading the soil’s story

Heavy metal contamination in cropland varies by region, often shaped by geology, land use history, and water management. Across central and south-east Asia, rice fields are irrigated with groundwater that naturally contains arsenic. That water deposits arsenic into the soil, where it is taken up by the rice.

Fortunately, nature often provides defence. Recent research showed that certain types of iron minerals in the soil can convert arsenite – a toxic, mobile form of arsenic – into arsenate, a less harmful species that binds more tightly to iron minerals. This invisible soil chemistry represents a safety net.

In parts of west Africa, such as Burkina Faso, arsenic contamination in drinking and irrigation water has also affected croplands. To address this, colleagues and I developed a simple filtration system using zerovalent iron – essentially, iron nails. These low-cost, locally sourced filters have shown promising results in removing arsenic from groundwater.

In parts of South America, croplands near small-scale mines face additional risks. In the Amazon basin, deforestation and informal gold mining contribute to mercury releases. Forests act as natural mercury sinks, storing atmospheric mercury in biomass and soil. When cleared, this stored mercury is released into the environment, raising atmospheric levels and potentially affecting nearby water bodies and croplands.

Cropland near legacy mining sites often suffers long-term contamination but with the appropriate technologies, these sites can be remediated and even transformed into circular economy opportunities.

Evidence-based solutions

Soil contamination is not just a scientific issue. It’s a question of environmental justice. The communities most affected are often the least responsible for the pollution. They may farm on marginal lands near industry, irrigate with unsafe water, or lack access to testing and treatment. They face a double burden: food and water insecurity, and toxic exposure.

There is no single fix. We’ll need reliable assessment of contaminated soils and groundwater, especially in vulnerable and smallholder farming systems. Reducing exposure requires cleaner agricultural inputs, improved irrigation, and better regulation of legacy industrial sites. Equally critical is empowering communities with access to information and tools that enable them to farm safely.

Soils carry memory. They record every pollutant, every neglected regulation, every decision to cut corners. But soils also hold the potential to heal – if given the proper support.

This is not about panic. It’s about responsibility. The Science study provides a stark but timely reminder that food safety begins not in the kitchen or market but in the ground beneath our feet. No country should unknowingly export toxicity in its grain, nor should any farmer be left without the tools to grow food safely.![]()

——————————

This blog is written by Dr Jagannath Biswakarma, Senior Research Associate, School of Earth Sciences and Cabot Institute for the Environment, University of Bristol. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.