|

| Fog Bridge. Image by Freya Sterling. |

This year, as part of its contribution to Bristol 2015, European Green Capital, the In Between Time Festival commissioned the Fog Bridge by internationally renowned artist Fujiko Nakaya. She shrouded Pero’s Bridge in fog, eliciting a combination of delight and introspection – as well as befuddling the occasional commuter. The Fog Bridge stimulated debate, criticism, celebration and interest. The most interesting of those debates, that I hope are only starting, revolve around its impact. Like all great art, Fog Bridge should be and is a bit dangerous, in that it causes us to consider – if even for a while – some alternatives to our perspectives. But who saw it and engaged with it? Has it affected belief systems and values? Has it changed behaviour and, if so, of whom? And is that all a bit too much of a burden to put onto a single piece?

Nonetheless, it certainly stimulated discussion and that was its primary aim. It was my good fortune to be asked to reflect on Fog Bridge and be involved with an event of this stature. Some of those conversations contributed to the themes explored during the Festival: Enter the Storm, including a focus on living with uncertainty. And part of that was my participation in the Festival’s Uncertainty Cafes (see more here). I was asked to throw out ideas – some well informed and some more adventurous – and then partake in the fascinating conversations this artwork had stimulated. In that spirit, I share the following unabridged transcript of what I spoke about at the Uncertainty Café on 13 Feb

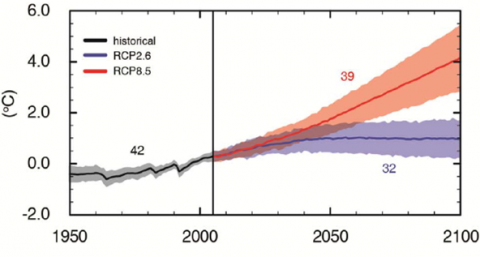

Our world has always changed. I have spent over 20 years studying the history of our planet’s climate and environment, and one of the most recurring themes is that on long enough timescales, change rather than stasis is the norm. But the coming changes to our climate, arising from our lifestyles and consumption, are distinct in their speed. They are nearly unprecedented in Earth history and they are certainly unprecedented in human experience. The Earth is warming, the oceans are acidifying, sea level is rising, droughts and floods are becoming more frequent – and we as a people are being challenged to adapt to these changes. One of the most profound challenges is not the higher temperature of more frequent flood but the uncertainty associated with those. Change, almost by definition, imposes uncertainty and we must discover how to live in this increasingly Uncertain World.

We live our lives informed by the power of experience: the collective experience of ourselves, our families, our communities and our wider society. Our weather projections and crop harvesting, our water management and hazard planning are also based on experience: tens to hundreds of years of observation that inform our predictions of future floods, drought, hurricanes and heat waves. Now, however, we are changing our environment and our climate, such that the lessons of the past have less relevance to the planning of our future. As we change our climate, the great wealth of knowledge generated from human experience is losing value every day.

|

| Fog Bridge. Image by Freya Sterling. |

This is how I am provoked by all of Fujiko Nakaya’s art and especially her wonderful Fog Bridge. Yes it makes me think about our changing weather. Yes, it serves as an enigmatic warning of the Coming Storm. But more, the image of fog, the obstruction of our vision, the demand for a more careful navigation over a bridge that is normally one of our most reliable paths, makes me think of an Uncertain World.

|

| Fog Bridge. Image by Freya Sterling. |

Uncertainty is a challenge. Uncertainty makes it harder for us to live with our planet and with each other. But there is something gentle about the uncertainty evoked by the Fog Bridge that invites alternative perpectives. Is an environmental disaster the only possible outcome of the path on which we walk?

Fifty years ago, between 1962 and 1966, J. G. Ballard wrote a trio of seminal environmental disaster novels: The Drowned World, The Burning World and The Crystal World. That is why one of the Cabot Institute’s themes this year is The Uncertain World. But there is a more nuanced lesson from Ballard when it comes to change: ‘I would sum up my fear about the future in one word: boring.’ In many ways, that statement, like the Fog Bridge, challenges the idea of uncertainty being solely negative. I think much of what is embedded in that statement is reflected in Ballard’s post-disaster novels – from Crash to High Rise to Cocaine Nights, all dealing with the tedium of late 20th century, bored lives, gated retirement villages on the Costa del Sol, manicured lawns, 99 channels with nothing on.

And what a tragedy that is for our species. Our most unique and exceptional characteristics are adaptability, imagination and creativity. Most of our achievements and many of our sins are a direct consequence of our incredible ability to adapt and create. We can live in the desert, in Antarctica, in space.

If we return to Ballard’s environmental disaster novels with this perspective, they take on new shapes. The protagonists in those novels – and especially the Drowned World – are not destroyed. Nor do they overcome. They are awakened and they are transformed. And in the end, they embrace those transformations:

“By day fantastic birds flew through petrified forests, and jewelled crocodiles glittered like heraldic salamanders on the banks of the crystalline river. By night the illuminated man raced among the trees, his arms like golden cartwheels, his head like a spectral crown.” – The Crystal World, J.G. Ballard

Catastrophic change can be beautiful and it can startle us out of complacency, it can challenge us, it can demand of us that we embrace the entirety of human potential.

But there are limits to this train of thought.

Taking that perspective towards global environmental disaster is the rather unique luxury of the upper middle class, privileged western European. Those who might die in floods or famines or whose way of life is not changed but obliterated by rising sea levels will have a different perspective. Let us never forget that those bringing about climate change and those likely to suffer most from it are not the same. That is true globally and it is true in Bristol: if the price of food doubles, I will grumble; others will be unable to feed their families.

And in that is a deep and unsettling irony. Those of us who perhaps would benefit most from embracing the challenges we face are profoundly reluctant to accept any change, whether that be to our sources of energy or food, to our way of lives or to our growth-based economy. And our inability to envision societal change is imposing potentially catastrophic environmental and climatic change on others – those who are most poor and most vulnerable.

That is why the Green Capital conversations must focus on issues of inclusion, empowerment and social justice. We must avoid unfair, unequal, unethical change. But if we can do that, then maybe change can be a catalyst for something fresh and exciting. Fujiko’s Fog Bridge is beautiful. Fog is beautiful. A storm is beautiful. This does not have to be a Disaster Story. We can change how we live, thereby mitigating the most dangerous aspects of climate change. And when we fall short and change does come… we can fight it a bit…. But we can also embrace it.

And what might that look like?

We must be radically resilient. If radical uncertainty is on the way then our response must be radically flexible. Our buildings and roads must be able to change. Our railroads and our health service. Our laws. Our jobs. Our economy. Our businesses. Ourselves.

Our response must be fair and equitable. Those who can barely afford the rent or who work two jobs to put food on the table have less capacity to be flexible. Some of us will have to bear more of the burden of change than others. Ultimately, I believe we will have to achieve a more fair and balanced society: It is difficult to imagine how grand challenges of resource and planetary sustainability can be achieved if billions are held back by poverty. [NB. This paragraph was the most difficult to express in only a few words during the Uncertainty Café and I want to expand on this here. I believe that everyone in society has great assets of imagination and creativity. All communities and all individuals can make a positive difference and should be encouraged to do so – and supported in doing so. And in the future, as throughout history, some of the most exciting ideas will come from some of the poorest on our planet. But overall, I think that poverty steals time and lost time means lost ideas. And that is a tragedy at a time when we need a proliferation of new ideas, and especially those that run counter to ‘conventional wisdom’.]

And we need political inclusion. If difficult choices are to be made – if our sacred cows are to be sacrificed or compromises are to be made – then we must rebuild a universally owned political system. We will not weather any storm by hectoring and lecturing nor if mired in apathy and cynicism. I sincerely hope a new platform for more inclusive decision making is a major outcome of Bristol 2015. It is certainly the ambition of the Green Capital Partnership.

If we share these risks and the costs, then perhaps we can collaborate with our changing planet to achieve something exciting and new – lifestyles that embrace rather than stifle the very best of our creative, dynamic and resilient nature. Maybe we walk across the Bridge a bit more slowly, maybe we don’t cross it at all, maybe we just stop and stare. I don’t know. Nor do I know if we will make such dramatic changes. But I know that we can.

This blog is by Prof Rich Pancost, Director of the Cabot Institute at the University of Bristol.

|

| Prof Rich Pancost |