|

| Graphic by Sarah Harman. Taken from energy.gov. |

Electricity systems are undergoing rapid transformation. An increasing share of previously passive consumers is defecting energy demand and supply from the public electricity network (grid) as active ‘prosumers’ while technological and business model innovation is enabling demand-side resources to provide reliable and cost competitive alternatives to supply capacity.

Yet, centralised supply-focused market structures dominated by legacy infrastructures, technologies and supply chains associated with path-dependencies and technological lock-ins continue to dominate. Regulation has been designed around these existing supply-focused markets and structures rather than networks of the future capable of integrating and facilitating smart, flexible systems. Current systems and their regulatory frameworks are struggling to engage and integrate a range of technological, economic and social innovations promising consumer-oriented solutions to environmental problems.

In the UK, the Office for Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem) regulates the electricity and gas markets to protect the interest of existing and future consumers. Ofgem acknowledges that ‘moving from a largely centralised, carbon-intensive model to one which will be increasingly carbon-constrained, smart, flexible and decentralised is creating challenges which can only be addressed by innovation’.

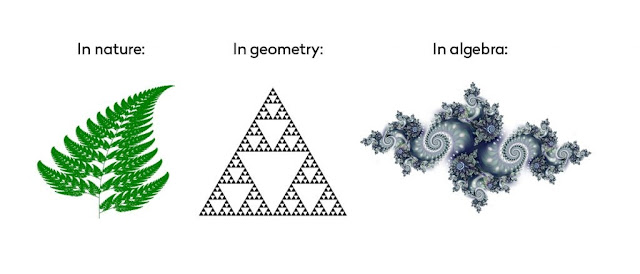

In practice, the rapid diffusion of emerging digital technologies such as smart grids, smart meters and the internet of things is disrupting market structures and business models. Progress in automated and machine learning is producing exponentially growing amounts of data which facilitates the deep learning required for more accurate time series predictions. At the same time, distributed ledger technologies such as blockchain provide combined digital accounting and measuring, reporting and verification infrastructures as well as a means of developing and executing smart contracts.

Regulators such as Ofgem are confronted with the need to ‘keep the lights on’ while balancing their primary focus of regulating centralised electricity supply and trading markets with engaging with disruptive innovations. This is reflected in Ofgem’s monolithic, centralised structure, despite its commitment to facilitating smart systems, flexibility and non-traditional business models.

The question is, how can the regulator square grid code written for large-scale generators and wholesale traders with an increasing understanding of and desire to facilitate smart, flexible systems?

Disruptive technologies and business model innovation

In practice, smart, flexible systems imply the bidirectional flow of information which relies on a combination of on storage, demand-side responses, interconnection and energy efficiency increasingly facilitated by emerging digital and distributed ledger technologies. It is evident that existing legal frameworks will need to change to accommodate emerging digital and distributed ledger technologies, but regulators need to proceed with caution and change is inevitably a slow process that needs to take a very wide range of statutory and non-statutory requirements into account. Up to that point, however, the regulators’ discretionary and exempting power can and should be applied (with caution).

In Europe, Ofgem is at the forefront alongside the Dutch regulator (Authority for Consumers and Markets – ACM) in providing ‘regulatory sandboxes’ for microgrids and peer-to-peer trading which facilitates buying and selling electricity locally. These sandboxes facilitate experimentation and innovation without companies incurring or being subject to established regulatory requirements.

Despite Ofgem’s commitment to providing space for experimentation and innovation, missing market rules and high entry barriers encourage innovators to seek alternatives through regulatory defection. Two reports by the Rocky Mountain Institute, one on load defection and one on grid defection sensitised research and policy communities to economic aspects of electricity market defection. Regulatory defection is another aspect of the same issue but it deals with the broader opportunity (and concern) of economic activity shifting beyond particular regulatory spaces and boundaries. Arguments have been put forward that the trend of government withdrawing from energy policy rewards regulatory defection in electricity markets.

Concrete examples of regulatory defection in the electricity market include engaging in behind the meter generation, private wire supply and microgrids. Behind the meter generation is facilitated by a rapid fall in electricity storage costs. Batteries are now available for home installation with promises of 60% savings on electricity bills if appropriately scaled to match on-roof solar PV generation. Behind the meter generation also includes anything else that can be done to limit engagement with the grid, including energy efficiency improvements and reducing demand.

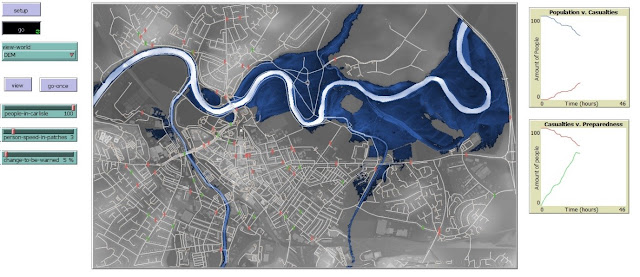

Private wire supply and microgrids require the installation of dedicated physical electricity transmission infrastructure. Private wire enables generators to sell electricity to neighbouring premises without transmitting electricity through the grid. Microgrids take private wires a step further to include a private network across multiple sites and end consumers. These arrangements are complex and require considerable skills and capacity to engage with appropriate network design, infrastructure, installation costs, land and planning requirements and operation and maintenance.

Despite this complexity, regulatory defection is underway through behind the meter generation, private wire supply and microgrid development. For example, Easton Energy Group in Bristol is at the forefront of developing a community microgrid combining solar PV generation with battery storage and dedicated transmission infrastructure as part of their TWOs project.

Energy Service Company (ESCO) business models facilitate defection by shifting the emphasis on the delivery of energy services. Rather than delivering energy in the form of grid electricity or fuel, ESCOs deliver final energy services such as lighting, ventilation or refrigeration. By shifting profitability towards the efficient provision of these services at low energy and environmental costs, ESCOs shift economic activity beyond the scope of electricity market regulation.

Combined, behind the meter generation, private wire supply and microgrids on the one hand, and ESCO business models on the other, require a rethink of how electricity is regulated. Fairness and equity need to be prioritised to ensure that the costs of running the existing infrastructure (which will still be necessary no matter how rapidly distributed systems evolve) will not be borne by fewer and less fortunate consumers that lack the capacity to defect. Therefore, new regulatory approaches are required to ensure that clean energy will be available to all at affordable costs.

Embracing disruption

One way of engaging with change is by embracing the innovations that threaten to usurp the current system. The Chilean regulator, Commisión Nacional de Energía (CNE), considers Blockchain an essential element of fair and sustainable energy markets. Its web portal Energía Abierta, the 1st open data website in South America, uses Blockchain as a digital notary. It allows CNE to certify that information provided on the web portal has not been altered and modified while also leaving an immutable record of its existence.

To this end, CNE issues ‘certificates of trust’ to give greater credibility to the portal. The aim of the portal is to increase levels of trust among stakeholders and the general public that have access to and consume the portal’s data. Another aim is that by using blockchain, greater trust in the citizen-government relationship can be created through more open and transparent governance. Ultimately, CNE expects blockchain to increase traceability, accountability, transparency and trust.

Chile has taken the lead in using blockchain as part of its regulatory framework and other countries should learn from this experience, especially if blockchain is to fulfil its potential in reducing transaction costs and managing complexity. Combining distributed ledger technologies such as blockchain with emerging digital technologies such as smart grids, smart meters and the internet of things can provide a new platform for electricity market regulation with data embodied in electricity at its core rather than electricity by itself.

The problem with regulation, however, is that it is based on experience from the past. Regulating emerging technologies and facilitating beneficial outcomes while limiting potential negative ones requires a fine balance and technological agnosticism. In this context it is necessary to bear in mind that it is not Ofgem’s sole responsibility to alter regulation. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), District Network Operators, the National Grid and combined industry code panels governed by the Competition and Markets Authority and determined by the Secretary of State also have a role to play.

Regulatory defection in electricity markets will continue progressing in the absence of new market structures. Maybe it is time to rethink electricity market regulation in this space along the lines of platform regulation?

—————————

This blog has been written by Cabot Institute member Dr Colin Nolden, Vice Chancellor’s Fellow researching in Sustainable City Business Models (University of Bristol Law School).

|

| Colin Nolden |