We’ve long known that environmental factors – from humidity and temperature to trace chemical vapours – can influence how pathogens, such as viruses, bacteria and fungi, behave once released into the air. These tiny droplets of respiratory fluid, or aerosols, carry viruses and bacteria and can float for minutes or even hours. But while we’ve been busy focusing on physical distancing and surface cleaning, a quieter factor may have been playing a much bigger role in airborne disease transmission all along: carbon dioxide (CO₂).

During the pandemic, we studied what happens to a virus when it travels through the air in tiny droplets from our breath – known as aerosols. In earlier research, we found that the droplet’s pH (how alkaline it is) can affect how quickly the virus loses its ability to infect people. Our more recent research, though, suggests that CO₂ levels in indoor air may significantly affect how long viruses survive once airborne – and the implications are profound.

Airborne virus survival

When someone coughs, sneezes, talks or sings, they release microscopic droplets into the air. These droplets start out in a warm, moist and CO₂-rich environment inside the lungs, where CO₂ levels reach a staggering 38,000 parts per million (ppm). Once expelled, they encounter the cooler, drier and typically much lower-CO₂ environment of indoor or outdoor air. This rapid change triggers a chain reaction inside the droplet.

One key component inside these droplets is bicarbonate, which acts as a buffer and is formed when CO₂ dissolves in liquid. As CO₂ diffuses out of the droplet into the air, bicarbonate leaves with it. This causes the droplet’s pH to rise – becoming increasingly alkaline, sometimes reaching pH 10.

Why does this matter? Viruses like COVID-19 don’t like alkaline environments. As the pH rises, their ability to infect decreases. In other words, the higher the pH, the quicker the virus becomes inactive. However, when the ambient CO₂ concentration is high, this pH shift is delayed or minimised, meaning the virus remains in a more hospitable environment – and stays infectious longer.

What role does CO₂ play?

While CO₂ doesn’t transmit viruses itself, it acts as a proxy for indoor crowding and poor ventilation. The more people in a space, the more CO₂ builds up from exhaled breath. When there isn’t enough ventilation, these levels stay high as do the chances that airborne viruses can linger longer and infect others.

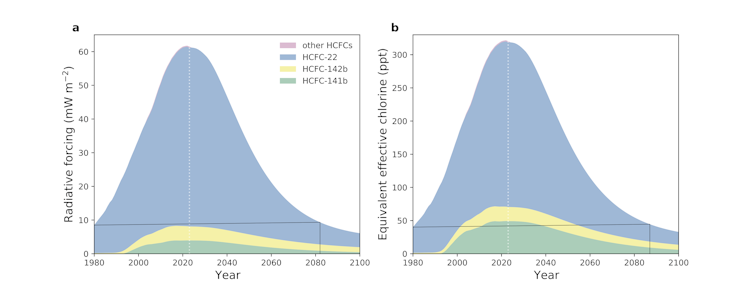

Outdoor CO₂ levels are around 421ppm, but in crowded or poorly ventilated spaces, indoor levels can easily exceed 800ppm. That’s the tipping point identified in the study, where the air starts allowing droplets to maintain a lower pH, increasing the survival time of viruses. In the 1940s, global CO₂ levels were much lower – around 310ppm – meaning indoor air offered less of a survival advantage to airborne pathogens.

Looking ahead, climate projections estimate CO₂ levels could reach 685ppm by 2050, making this issue not only one of pandemic response but also of climate and public health policy. If we don’t address this now, we may be heading into a future where viruses survive longer in the air due to everyday indoor conditions.

Can we fix it?

The good news? These findings suggest solutions we can implement right now.

First, improve indoor ventilation. Increasing airflow and introducing outdoor air into enclosed spaces dilutes both CO₂ levels and any virus-containing aerosols. This simple change can significantly reduce the risk of airborne transmission – not just for COVID-19, but for future respiratory viruses as well.

And, in the not-too-distant future, we might have indoor carbon capture technology. These devices, which are still being developed, could help remove excess CO₂ from the air, especially in hospitals, classrooms and public transport where the risk of spreading illness is higher.

Also, monitoring indoor CO₂ levels using affordable sensors can empower individuals, schools and businesses to assess the indoor air quality and adjust the ventilation accordingly. If CO₂ levels rise above safe thresholds (often considered about 800ppm), it’s time to open windows, use air purifiers or ask some people to leave the room.

This research reshapes the way we think about air quality. It’s no longer just about stuffiness or comfort – it’s about infection risk. As we face rising global CO₂ levels and continue to recover from the COVID pandemic, it’s clear that managing indoor air environments is essential to public health.

By taking CO₂ seriously – not just as a climate metric but as a health indicator – we have a unique opportunity to reduce disease transmission in our everyday environments. Because when it comes to viruses in the air, the air itself might be our greatest ally – or our biggest threat.![]()

—————————-

This blog is written by Dr Allen Haddrell, Research Fellow, School of Chemistry, University of Bristol and Dr Henry Oswin, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Faculty of Science, School of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences, Queensland University of Technology. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.