Examining some of the Fund’s shortcomings and putting things into perspective after COP 28

COP 28, the latest United Nations Climate Conference, came to an end in December 2023. It began with an agreement to launch the loss and damage fund, which was kick-started by the UAE’s $100 million pledge. A further 15 countries followed suit, making pledges of varying amounts, and by 2 December 2023, a cumulative total of $655.9 million had been pledged to the loss and damage fund.[1] The fund has been heralded by many as the biggest success of the entire conference and a historic agreement – being the first time that a substantive decision was adopted on the first day of the Conference. The delegates of nations present from around the world, rose in a standing ovation when the agreement was passed.

However, although the loss and damage fund is an important and long overdue step towards getting vulnerable countries and communities funding they require, it may be too soon to be rejoicing, with many of the details regarding the fund’s set-up being highly controversial.

A brief background to the loss and damage fund

The loss and damage fund was first agreed to at COP 27 last year, after more than three decades of pressure from developing countries disproportionately affected by the irreversible and adverse consequences of climate change calling for funding to help them pay for the losses and damages suffered as a result of the escalating climate crisis. These impacts range from, and are caused by, increasingly frequent and more extreme weather events, as well as slow-onset events, including sea-level rise, increasing temperatures, ocean acidification, glacial retreats, loss of biodiversity, land and forest degradation, salinisation and desertification. These endanger human security and health, destroy homes, disrupt agriculture and threaten water and food security in ways that are often unequally distributed.

As one of the outcomes of COP 27, a Transitional Committee was established and, in the lead up to COP 28, they met several times to negotiate the operationalisation and the details of the new funding arrangements. In less than a year, the Transitional Committee were able to report back with its recommendations and its text was subsequently passed at COP 28, with no objection by the parties. After almost no momentum for thirty years, the progress made in less than a year is a remarkable feat.

Examining some of the shortcomings

While funding for climate disaster loss and damages is vital and certainly hard fought for, one should be hesitant before deeming it a substantive win for developing countries.

Inadequate and duplicate pledges

Although $655.9 million may at first glance appear like a significant amount of money, it is in fact relatively insubstantial when one considers that it is estimated that more than $400 billion is suffered in losses by developing countries each year,[2] a figure which is expected to grow as the impacts of climate change grow worse. The current funding will therefore cover less than 0.2% of developing countries’ annual needs. It has therefore been recommended that $400 billion be used as a baseline and revised upwards over time to meet increasing needs.[3] Furthermore, how to actually implement the pledges that have been made poses its own issue. This is a problem that previous funds, such as the Green Climate Fund, have faced and it is an issue that will need to be tackled to ensure that the pledges made do not simply turn out to be more broken promises. Moreover, approximately $115.3 million of the total amount pledged to date will go towards setting up the fund rather than directly to beneficiaries of the fund.[4] Future pledges to the fund may make this operational expense insignificant, but it is still uncertain how much money will go into the fund and where it will come from. In addition, campaigners pointed out that some countries, such as the United Kingdom, were simply re-pledging money that they had already committed to, rather than offering new or additional funding.[5] In this way, the United Kingdom are simply re-branding existing forms of climate finance or development aid so as to appear to be contributing.

Moreover, the amount pledged by some countries has been criticised for being inadequate. In particular, the United States, the world’s largest historical emitter[6] and the largest producer and consumer of oil and gas in 2023,[7] pledged only $17.5 million, an amount that still needs to be approved by Congress and accordingly hinges on the political climate and the upcoming elections. When viewed against the billions of dollars of undelivered climate finance that the United States owes to developed countries as part of its share of the annual $100 billion climate finance goal committed to by developed countries in 2009, this amount of $17.5 million certainly appears limited.[8] Of the $43.51 billion the United States owes, as part of its fair share of the $100 billion goal, only $9.27 billion has been provided to date, being a measly 21% of its targets.[9]

It is also very telling as to what the United States’ priorities are when the $17.5 million pledged by the United States to the loss and damage fund is compared to the estimated annual $20.5 billion in fossil fuel subsidies distributed by the United States government each year,[10] contributing to the cumulative amount of $7 trillion in fossil fuel subsidies in 2022.[11]

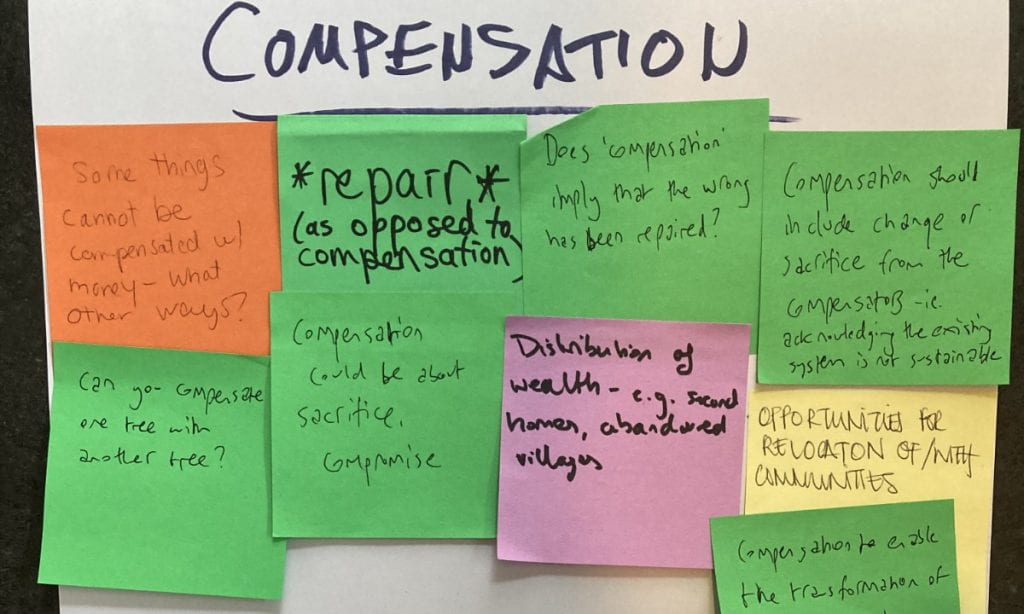

Historical responsibility and voluntary contributions

During the negotiations that the Transitional Committee had leading up to COP 28, the United States, Australia and Canada all insisted that the loss and damage fund be de-linked from liability or compensation. This is in keeping with previous stance adopted by developed countries, particularly with that of the United States, who insisted that this wording be included in the decision on the adoption of the Paris Agreement which noted that loss and damage was “not a basis for liability or compensation”.[12] As the historically greatest emitters, developed countries have long opposed the establishment of the loss and damage fund over concerns that it would open the door to legal liability and compensation. Due to this refusal to assume historical accountability, communities who are experiencing the worst impacts of climate change have been forced to shoulder the consequent costs of loss and damage suffered, even though many of them, such as the Pacific Small Island Developing States, have contributed very little to climate change. This goes to the issue of equity and responsibility for the climate crisis, a sensitive topic which makes developed countries defensive. Instead of framing loss and damage in terms of responsibility and liability, wording was included in the agreed text stating that the fund is based on cooperation and facilitation.

The approved text also stops short of demanding any payments, with the United States having fought to ensure that the contributions should remain voluntary, and the text indicated that developed countries ought to “take the lead” on providing seed money. The text “urged” developed countries to contribute to the fund, while other developing countries are “encouraged” to provide support “on a voluntary basis”.[13] The United States, Australia and Canada further insisted that contributor countries include presently high-polluting nations such as China, India, Russia and Saudia Arabia, and that only the least developed countries be eligible to benefit from the fund. As a result, high polluter states are not obligated to make any payments into the fund and instead of framing the contributions in terms of countries’ responsibility for the majority of greenhouse gas emissions, they are framed as donations made out of generosity and charity.

The World Bank as the interim host of the Loss and Damage Fund, the set-up of the Fund’s governing board and the structure of funding

Who would host and administer the new fund was a politically contentious sticking point in the discussions leading up to COP 28. Less than a month before COP 28, at a final and impromptu meeting called by the Transitional Committee, this matter was hastily decided. Developing countries wanted the loss and damage fund to operate as an independent United Nations body and were resistant to it being hosted by the World Bank, which many poorer countries see as an economic policy weapon wielded by the industrialised world.

The World Bank was established by colonial powers and is known for having historically spread pro-Western ideologies and policies.[14] Moreover, it is housed in Washington DC, is headed by a US citizen, appointed by the government of the United States, as its major shareholder,[15] and has a history of operating as an Untied States policy tool. In addition, concerns were raised that the World Bank would be charging high hosting fees, has a weak climate change record and that having it host and administer the loss and damage fund would compromise the fund’s independence and give developed countries the influence over who receives the funds and who doesn’t. Developing countries eventually caved under the United States’ insistence that the fund be hosted and administered by the World Bank, and it was agreed that the World Bank would act as an interim host, provided that the World Bank would agree to certain conditions. This arrangement is to be reassessed in four years, which will result in either the fund being made fully independent or continuing as a permanent hosting situation under the World Bank.

The United States has argued that there are practical reasons for placing the loss and damage fund under the auspices of the World Bank, and that the fiduciary experience the institution has, places it in the best position to deliver money to state beneficiaries. However, given the World Bank’s donor-recipient and loan-driven business model, reservations have been expressed as to whether developed donor countries would have a disproportionate influence, even though the Transitional Committee has recommended that the fund’s governing board have a majority of developing-country members. Although this sounds positive, the board’s composition is limited to national representatives, meaning that civil society representatives such as members of Indigenous groups, are automatically excluded.

Another concern regarding the World Bank, is high overhead costs, with the administrative fees of the World Bank rising and likely to absorb a large portion of the funding meant for the fund’s beneficiaries. Further, developing countries have consistently called for funding to be in the form of grants, rather than debt and loan financing, which would only deepen the debt crisis and increase developing countries’ burden, which is the traditional model of financing employed by the World Bank. The agreed text stipulates that “the Fund will provide financing in the form of grants and highly concessional loans”.[16]

The ultimate success or failure of the loss and damage fund still hangs in the balance

In order to retain any faith in the international climate policy process, there needs to be follow-through on both the pledges and commitments made. To date, climate finance has not had the best track record. Other funds, including the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund, have been radically under-resourced from the get-go and climate finance has grown at an annual rate of only 7%, which is less than half of the cumulative annual growth of 21% which is required until 2030.[17] In order for the Loss and Damage Fund to be effective, the scale of the funding will need to be increased, as what has been pledged to date constitutes a mere 0.2% of what is actually needed.

There are also still a lot of questions to address, which the new Board of the Loss and Damage Fund will start to work through at its first meeting on 31 January 2024. Popular Gentle, the development management expert to the prime minister of Nepal, pointed out that while the establishment of the loss and damage fund is a promising start, that applause should be reserved for the time being, saying “our concern is we are excited about the establishment of the loss and damage fund. We are still cautious that the same story will be repeated. We need easy, equitable, accessible loss and damage funds without any procedural difficulties”.[18]

So far, there are already some concerning issues that have arisen out of what has been decided. The issues that still need to be determined will prove critical to whether the fund’s operation is a success or a failure. These issues include the fact that there are no specifics yet on the scale and scope of funding, the financial targets or how the loss and damage fund will be funded going forward – although the text provides that contributions will come from a “variety of sources”.[19] The current language included in the agreed text merely invites developed nations to “take the lead”[20] in providing finance and encourages other developing country parties to make commitments. There is also little clarity regarding the performance indicators and who will be eligible to receive funding or precisely what type of climate loss and damages will qualify. Another issue will be how the application procedure will work and how quickly countries who need it will be able to access the funds and whether they will encounter any procedural difficulties in doing so. Until these things are decided, it is simply too early to greet the loss and damage fund with anything other than a mixture of cautious optimism and healthy scepticism.

References

[1] Joe Thwaites ‘COP28 Climate Funds Pledge Tracker’ (NRDC, 9 December 2023), available at: https://www.nrdc.org/bio/joe-thwaites/cop-28-climate-fund-pledge-tracker

[2] Julie-Anne Richards, Rajib Ghosal, Brenda Mwale, Hyacinthe Niyitegeka and Moleen Nand ‘STANDING IN SOLIDARITY WITH THOSE ON THE FRONTLINES OF THE CLIMATE CRISIS: A LOSS AND DAMAGE PACKAGE FOR COP 28’(The Loss and Damage Collaboration, 20 November 2023), available at: https://assets-global.website-files.com/605869242b205050a0579e87/655b50e163c953059360564d_L%26DC_L%26D_Package_for_COP28_20112023_1227.pdf

[3] Julie-Anne Richards, Liane Schalatek, Leia Achampong, and Heidi White ‘THE LOSS AND DAMAGE FINANCE LANDSCAPE’ (The Loss and Damage Collaboration, 16 May 2023), available at: https://www.lossanddamagecollaboration.org/publication/the-loss-and-damage-finance-landscape

[4] ‘COP 28: Key outcomes agreed to at the UN Climate talks in Dubai’ (Carbon Brief, 13 December 2023), available at: https://www.carbonbrief.org/cop28-key-outcomes-agreed-at-the-un-climate-talks-in-dubai/

[5] Tweet on X (CAN-UK 30 November 2023), available https://twitter.com/CAN_UK_/status/1730225613456204089?s=20

[6] ‘Cumulative carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions from fossil fuel combustion worldwide from 1750 to 2022, by major country’ (Statistica, 12 December 2023), available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1007454/cumulative-co2-emissions-worldwide-by-country/#:~:text=Global%20cumulative%20CO%E2%82%82%20emissions%20from,combustion%201750%2D2022%2C%20by%20country&text=The%20United%20States%20was%20the,birth%20of%20the%20industrial%20revolution

[7] World Population Review, available at: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/oil-producing-countries; https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/oil-consumption-by-country; https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/natural-gas-by-country

[8] At the 15th Conference of Parties (COP15) of the UNFCCC in Copenhagen in 2009, developed countries committed to a collective goal of mobilising USD 100 billion per year by 2020 for climate action in developing countries, in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation. The goal was formalised at COP16 in Cancun, and at COP21 in Paris, it was reiterated and extended to 2025; Laetitia Pettinotti, Yue Cao, Tony Mwenda Kamninga, Sarah Colenbrander ‘A fair share of climate finance? The Adaptation Edition’ (ODI, 13 September 2023), available at: https://odi.org/en/publications/a-fair-share-of-climate-finance-the-adaptation-edition/#:~:text=In%20a%20bid%20to%20strengthen,national%20income%2C%20and%20population%20size

[9] At the 15th Conference of Parties (COP15) of the UNFCCC in Copenhagen in 2009, developed countries committed to a collective goal of mobilising USD 100 billion per year by 2020 for climate action in developing countries, in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation. The goal was formalised at COP16 in Cancun, and at COP21 in Paris, it was reiterated and extended to 2025; Laetitia Pettinotti, Yue Cao, Tony Mwenda Kamninga, Sarah Colenbrander ‘A fair share of climate finance? The Adaptation Edition’ (ODI, 13 September 2023), available at: https://odi.org/en/publications/a-fair-share-of-climate-finance-the-adaptation-edition/#:~:text=In%20a%20bid%20to%20strengthen,national%20income%2C%20and%20population%20size

[10] Janet Redman ‘DIRTY ENERGY DOMINANCE: DEPENDENT ON DENIAL – HOW THE U.S. FOSSIL FUEL INDUSTRY DEPENDS ON SUBSIDIES AND CLIMATE DENIAL’ (Oil Change International, October 2017), available at: https://priceofoil.org/content/uploads/2017/10/OCI_US-Fossil-Fuel-Subs-2015-16_Final_Oct2017.pdf

[11] Simon Black, Ian Parry, Nate Vernon ‘Fossil Fuel Subsidies Surged to Record $7 Trillion’ (IMF Blog, 24 August 2023), available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/08/24/fossil-fuel-subsidies-surged-to-record-7-trillion

[12] UNFCCC 2015, Decision 1/CP.21, Adoption of the Paris Agreement, UN Doc FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add, para. 51, available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf

[13] Para 12 of Annex I ‘Draft decision on the operationalization of the new funding arrangements, including the fund, for responding to loss and damage referred to in paragraphs 2–3 of decisions 2/CP.27 and 2/CMA.4’ to the Report by the Transitional Committee dated 28 November 2023, FCCC/CP/2023/9−FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/9, available at: https://unfccc.int/documents?f%5B0%5D=topic%3A1136&search2=&search3=&page=0%2C0%2C0

[14] E Feder, ‘Plundering the Poor: The Role of the World Bank in the Third World’ (1983) 13 International Journal of Health Services 649, available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.2190/6GE4-8EC6-JXD5-QJ2Q

[15] The Congressional Research Service Report prepared for Members and Committees of Congress, titled ‘Selecting the World Bank President’ and updated 10 May 2023, available at: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R42463.pdf

[16] Para 57 of Annex II to the Report by the Transitional Committee dated 28 November 2023, FCCC/CP/2023/9−FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/9, available at: https://unfccc.int/documents?f%5B0%5D=topic%3A1136&search2=&search3=&page=0%2C0%2C0

[17] Baysa Naran, Jake Connolly, Paul Rosane, Dharshan Wignarajah, Githungo Wakaba and Barbara Buchner ‘The Global Landscape on Climate Finance: A Decade of Data’ (Climate Policy Initiative, 27 October 2022), available at: https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-a-decade-of-data/

[18] Lameez Omarjee ‘COP 28 I Pledges for Loss and Damage roll in, but billions is needed – SA chief negotiator’ (news24, 10 December 2023), available at: https://www.news24.com/fin24/climate_future/news/cop28-pledges-for-loss-and-damage-roll-in-but-billions-needed-sa-chief-negotiator-20231210

[19] Para 20 (i) of Annex I ‘Draft decision on the operationalization of the new funding arrangements, including the fund, for responding to loss and damage referred to in paragraphs 2–3 of decisions 2/CP.27 and 2/CMA.4’ to the Report by the Transitional Committee dated 28 November 2023, FCCC/CP/2023/9−FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/9, available at: https://unfccc.int/documents?f%5B0%5D=topic%3A1136&search2=&search3=&page=0%2C0%2C0

[20] Para 13 of Annex I ‘Draft decision on the operationalization of the new funding arrangements, including the fund, for responding to loss and damage referred to in paragraphs 2–3 of decisions 2/CP.27 and 2/CMA.4’ to the Report by the Transitional Committee dated 28 November 2023, FCCC/CP/2023/9−FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/9, available at: https://unfccc.int/documents?f%5B0%5D=topic%3A1136&search2=&search3=&page=0%2C0%2C0

———————–

This blog is written by Cabot Institute for the Environment member Alexia Kaplan.

.jpg)