Our current global warming target and the trajectory it places us on, towards a future ‘Hothouse Earth’, has been the subject of much recent discussion, stimulated by a paper by Will Steffen and colleagues. In many respects, the key contribution of this paper and similar work is to extend the temporal framing of our climate discussions, beyond 2100 for several centuries or more. Analogously, it is useful to extend our perspective backwards to similar time periods, to reflect on the last time Earth experienced such a Hothouse state and what it means.

The Steffen et al paper allows for a variety of framings, all related to the range of natural physical, biological and chemical feedbacks that will amplify or mitigate the human intervention in climate. [Note: the authors frame their paper around the concept of a limited number of steady state scenarios/temperatures for the Earth. They then argue that aiming for 2C, potentially an unstable state, could trigger feedbacks tipping the world towards the 4C warmer Hothouse. I find that to be somewhat simplistic given the diversity of climate states that have existed, if even transiently, over the past 15 million years, but that is a discussion for another day.] From my perspective, the most useful framing – and one that remains true to the spirit of the paper is this: We have set a global warming limit of 2C by 2100, with an associated carbon budget. What feedback processes will that carbon budget and warming actually unleash over the coming century, how much additional warming will they add, and when?

That is a challenging set of questions that comes with a host of caveats, most related to the profound uncertainty in the interlinked biogeochemical processes that underpin climate feedbacks. For example, as global warming thaws the permafrost, will it release methane (with a high global warming potential than carbon dioxide)? Will the thawed organic matter oxidise to carbon dioxide or will it be washed and buried in the ocean? And will the increased growth of plants under warmer conditions lead instead to the sequestration of carbon dioxide? The authors refer to previous studies that suggest a permafrost feedback yielding an additional 0.1C warming by the end of the century; but there is great uncertainty in both the magnitude of that impact and its timing.

And timing is the great question at the heart of this perspective piece. I welcome it, because too often our perspective is fixed on the arbitrary date of 2100, knowing full well that the Earth will continue to warm and ice continue to melt long after that date. In this sense, Steffen et al is not a contradiction to what has been reported from the IPCC but an expansion on it.

Classically, we discuss these issues in terms of fast and slow feedbacks, but in fact there is a continuum between near instantaneous feedbacks and those that act over hundreds, thousands or even millions of years. A warmer atmosphere will almost immediately hold more water vapour, providing a rapid positive feedback on warming – and one that is included in all of those IPCC projections. More slowly, soil carbon, including permafrost, will begin to oxidise, with microbial activity stimulated and accelerated under warmer conditions – a feedback that is only just now being included in Earth system models. And longer term, all manner of processes will come into play – and eventually, they will include the negative feedbacks that have helped regulate Earth’s climate for the past 4 billion years.

There is enough uncertainty in these processes to express caution in some of the press’s more exuberant reporting of this topic. But lessons from the past certainly underscore the concerns articulated by Steffen et al. We think that the last time Earth had 410 ppm CO2, a level similar to what you are breathing right now, was the Pliocene about 3 million years ago. This was a world that was 1 to 2C warmer than today (i.e. 2 to 3C warmer than the pre-industrial Earth) and with sea levels about 10 m higher. This suggests that we are already locked into a world that far exceeds the ambitions and targets of the Paris Agreement. This is not certain as we live on a different planet and one where the great ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica might not only be victims of climate change but climate stabilisers through ice-sheet hysteresis. And even if a Pliocene future is fixed, it might take centuries for that warming and sea level change to be realised.

But that analogue does suggest caution, as advocated by the Hothouse Earth authors.

It also prompts us to ask what the Earth was like the last time its atmosphere held about 500 ppm CO2, similar to the level needed to achieve the Paris Agreement to limit end-of-century warming below 2C. A useful analogue for those greenhouse gas levels is the Middle Miocene Climate Optimum, which occurred from 17 to 14.7 million years ago.

|

| Figure showing changes in ocean temperature (based on oxygen isotopic compositions of benthic foraminifera) and pCO2 over the past 60 million years (from Palaeo-CO2). Solid symbols are from the d11B isotope proxy and muted symbols are from the alkenone-based algal carbon isotope fractional proxy. Note the spike in pCO2 associated with the MMCO at about 15 million years ago. |

As one would expect for a world with markedly higher carbon dioxide levels, the Miocene was hotter than the climate of today. And consistent with many of Steffen et al.’s arguments, it was about 4C hotter rather than a mere 2C, likely due to the range of carbon cycle and ice-albedo feedbacks they describe. But such warmth was not uniform – globally warmer temperatures of 4C manifest as far hotter temperatures in some parts of the world and only slightly warmer temperatures elsewhere. Pollen and microbial molecular fossils from the North Sea, for example, indicate that Northern Europe experienced sub-tropical climates.

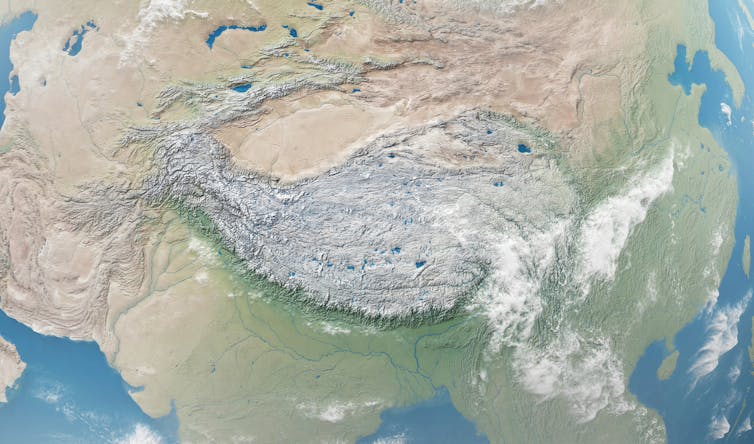

But what were the impacts of this warmth? What is a 4C warmer world like? To understand that, we also need to understand the other ways in which the Miocene world differed from ours, not just due to carbon dioxide concentrations but also the ongoing movement of the continents and the continuing evolution of life. In both respects, the Miocene was broadly similar to today. The continents were in similar positions, and the geography of the Miocene is one we would recognise. But there were subtle differences, including the ongoing uplift of the Himalayas and the yet-to-be-closed gateway between North and South America, and these subtle differences could have had major impacts on Asian climate and the North Atlantic circulation, respectively.

Similarly, the major animal groups had evolved by this point, and mammals had firmly established their dominance in a world separated by 50 million years from the dinosaurs. Remnant groups from earlier times (hell pigs!) still terrorised the landscape, but many of the groups were the same or closely related to those we would recognise today. And although hominins would not appear until the end of the Miocene, the apes had become well established, represented by as many as a 100 species. In the oceans, the differences were perhaps more apparent, the seas thriving with the greatest diversity of cetaceans in the history of our planet and associated with them the gigantic macro-predators such as Charcharadon megalodon (The MegTM).

|

| Smithsonian mural showing Miocene Fauna and landscape. |

But it is the plants that exhibit the most pronounced differences between modern and Miocene life. Grasses had only recent proliferated across the planet at the time of the MMCO, and the C4 plants had yet to expand to their current dominance. And in this regard, the long-term evolution of Earth’s climate likely played a crucial role. There are about 8100 species of C4 plants (although this comprises only 3% of the plant species known to us) and most of these are grasses with other notable species being maize and sugar cane. They are distinguished from the dominant C3 plants, which comprise almost all other species, by virtue of their carbon dioxide assimilation biochemistry (the Hatch-Slack mechanism) and their leaf cellular physiology (the Kranz leaf anatomy). It is a collective package that is exceptionally well adapted to low carbon dioxide conditions, and their global expansion about 7 million years ago was almost certainly related to the long-term decline in carbon dioxide from the high levels of the Middle Miocene. Although C4 plants only represent a small proportion of modern plant species, the Miocene world, bereft of them, would have looked far different than today – lacking nearly half of our modern grass species and by extension clear analogues to the vast African savannahs.

Aside from these, the most profound differences between the Miocene world and that of today would have been the direct impacts of higher global temperatures. There is strong evidence that the Greenland ice sheet was far reduced in size compared to that of today, and its extent and even whether or not it was a persistent ice sheet or an ephemeral one remains the subject of debate. Similarly, West Antarctica was likely devoid of permanent ice, and the East Antarctic Ice Sheet was probably smaller – perhaps far smaller – than it is today. And collectively, these smaller ice sheets were associated with a sea level that was about 40 m higher than that of today.

The hot Miocene world would have been different in other ways, including the hydrological cycle. Although less studied than for other ancient intervals, it is almost certain that elevated warmth – and markedly smaller equator-to-pole temperature differences – would have impacted the global distribution of water. More water was evidently exported to the high latitudes, resulting in a warmer and vegetated Antarctica where the ice had retreated. It was also likely associated with far more extreme rainfall events, with the hot air able to hold greater quantities of water. More work is needed, but it is tempting to imagine the impact of these hot temperatures and extreme rainfall events. They would have eroded the soil and flushed nutrients to the sea, perhaps bringing about the spread of anoxic dead zones, similar to the Oceanic Anoxic Events of the Mesozoic or the dead zones of modern oceans caused by agricultural run-off. Indeed, the Miocene is characterised by the deposition of some very organic-rich rocks, including the North Pacific Monterey Formation, speaking to the occurrence of reduced oxygen levels in parts of these ancient oceans.

****************************************************

It is unclear if our ambitions to limit global warming to 2C by the end of this century really have put us on a trajectory for 4C. It is unclear if we are destined to return to the Miocene.

But if so, the Miocene world is one both similar to but markedly distinct from our own – a world of hotter temperatures, extremes of climate, fewer grasslands, Antarctic vegetation, Arctic forests and far higher sea levels. Crucially, it is not the world for which our current society, its roads, cities, power plants, dams, borders, farmlands and treaties, has been designed.

Moreover, the MMCO Earth is a world that slowly evolved from an even warmer one over millions of years*; and that then evolved over further millions of years to the one in which we now inhabit. It is not a world that formed in a hundred or even a thousand years. And that leaves us three final lessons from the past. First, we do not know how the life of this planet, from coral reefs to the great savannahs, will respond to such geologically rapid change. Second, we do not know how we will respond to such rapid change; if we must adapt, we must learn how to do so creatively, flexibly and equitably. And third, it is probably not too late to prevent such a future from materialising, but even if it is, we still must act to slow down that rate of change to which we must adapt.

And we still must act to ensure that our future world is only 4C hotter and analogous to the Miocene; if we fail to act, the world will be even hotter, and we will have to extend our geological search 10s of millions of years further into the past, back to the Eocene, to find an even hotter and extreme analogue for our future Hothouse World.

*The final jump into the MMCO appears to have been somewhat more sudden, but still spanned around two-hundred thousand years. A fast event geologically but not on the timescales of human history.

——————————-

This blog is written by Cabot Institute member Professor Rich Pancost, Head of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol. This blog has been reposted with kind permission from Rich’s original blog.

|

| Rich Pancost |

![]()