|

| 1. Apocalypse, Albert Goodwin (1903.) At the culmination of 800 paintings, Apocalypse, was the first of Goodwin’s works in which he introduced experimental techniques that marked a distinct departure from the imitations of Turner found in most of his earlier works. [picture courtesy of the Tate online collection.] |

‘

Ask for what end the heav’nly bodies shine,

Earth for whose use? Pride answers, “Tis for mine:

For me kind Nature wakes her genial pow’r,

Suckles each herb, and spreads out ev’ry flow’r;

Annual for me, the grape, the rose renew

The juice nectareous, and the balmy dew;

For me, the mine a thousand treasures brings;

For me, health gushes from a thousand springs;

Seas roll to waft me, suns to light me rise;

My foot-stool earth, my canopy the skies.” ’

2. A section of the fifth (V) verse in the first epistle of Alexander Pope’s unfinished

Essay on Man, (1733-34.)

Alexander Pope, 18th Century moral poet, pioneer in the use of the heroic couplet, second most quoted writer in the Oxford dictionary of quotations behind Shakespeare and shameless copycat. Coleridge suggested this is what held Pope back from true mastery, but It is beyond question that the results of this imitation cultured some of the finest poetry of the era. Yet still, Pope, the bel esprit of the literary decadence that proliferated within 18th Century written prose and inspiration for the excellence of Byron, Tennyson and Blake, to name but a few; spent a large amount of his creative life imitating the style of Dryden, Chaucer, and John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester. The notion that Pope (2), and Albert Goodwin (1), such precocious and natural talents, would invest so much time in mastering the artistic style of others is curious indeed, it too, provides a broad entry-point for a discussion on the roles of imitation, mimicry and mimesis in human growth, social and societal development.

You live & you learn

Having now formulated a suitable appeal to emotion, which very narrowly avoids the bandwagon, it is worth noting that imitation, and it’s cousins repetition and practice too, represent the way in which an infant might copy its parent’s behaviour, how a young artist may seek a suitably influential model as a teacher or a musician may seek to imitate sounds and transpose these as a compliment to their own polyphony, are a fundamental component in epistemology; the building of knowledge. This understanding has become increasingly important for my own research, whereby repetition and practice have not only become a primary process in developing my own knowledge but have also been important methodological heuristics for establishing imitation and mimicry as primary, collective responses for human survival during exigent situations.

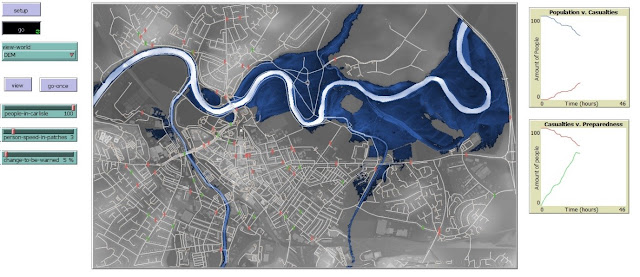

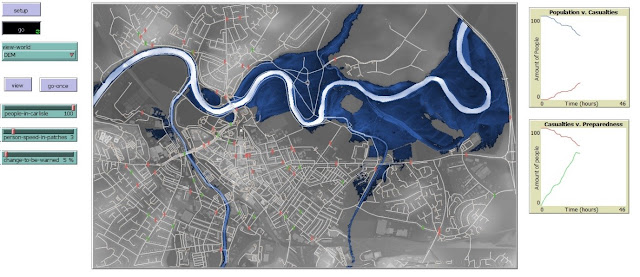

These responses and the systems within which they exist are inherently complex. In developing a robust framework to analyse and evaluate them in relation to flood scenarios for my research (3 and 4) I have utilised the agent-based model to emulate the human response to hydrodynamic data. If you have ever dealt with a HR department, any form of customer service, submitted an academic paper for publishing or bore witness to the wonders of automated passport control then you will be privy to the sentiments of human complexity, as well as our growing dependence on automation to guide us through the orbiting complexity of general life. Raillery aside, these specific examples are rather attenuated situations on which to base broad assessments of human behaviour. The agent-based model itself, a chimera rooted in computational science, born from the slightly sinister cold-war (1953-62) era overlap between computer science, biology and physics and so by implication possessing the ability to model many facets of these disciplines, their related sub-disciplines and inter-disciplines; can provide a panoptic of the broader complexities of human systems and develop our understanding of them.

|

| 3 (above) & 4 (below). Examples of the agent-based model designed for my own research. The scenario shown is for human response to flooding in Carlisle. The population at risk (green ‘agents’) go about their daily routine until impact from the flood becomes apparent, at which point individuals can choose to go into evacuation mode (red ‘agents’.) |

Academically, you may suggest that “these are bold claims!” (others certainly have!) tu quoque, I would retort “claims surely not beyond the horizons of your rationale or reasoning?” Diving deeper into the Carrollian involute of my research to underpin my quip (and readily expose myself to backfire bias) 12,000 simulations of the Carlisle flood case study with the aid of various choice-diffusion models to legitimise my computerised population’s decisions, have yielded a 66% preference for the population of Carlisle to interact with their neighbours and base their decision making on that of their social peers as opposed to following direct policy instruction. Broadly, this means that most of the computerised individuals respond to the flood by asking those around them what they are going to do, following their lead, imitating their evacuation decisions, mimicking their response to the flood.

Extrapolating beyond the confines of Carlisle, there are a great number of agent-based models that have explored the syncytia of human behaviours relative to systematic changes in their environment. Contra-academe and being a big fan of the veridical, I am happy to proclaim that my own model is a much wieldier alternative to the majority of those ‘big data’ models and so aims to demonstrate behavioural responses to events at a suitable point of balance between realism and interpretability. The agents represent individuals as close to reality as possible, they are defined by characteristics that define you, they and I – age, employment status etc. they are guided by self-interest and autonomously interact with a daily routine of choice that Joe public might undertake on an average day; they are (deep breath) meta-you, they and I as far as possibly mensurable, they do the same things, take the same missteps; even make the same mistakes* digitised and existent in an emulated environment replicant of ours.

(* not those kinds of mistakes.)

The cut worm forgives the plough

Veering this gnostic leviathan of an article away from the definite anecdotal and the convolvulus of complex system analysis, to what may well turn out to be a vast underestimation of reader credulity; the meat and water of this article has essentially been to provoke you into asking:

- To what degree can choice, imitation, mimicry, influence be separated out from one another?

- If the above is possible then how might they be measured?

- How can these measurements be verified?

- If verifiable then what implications do the outcomes carry?

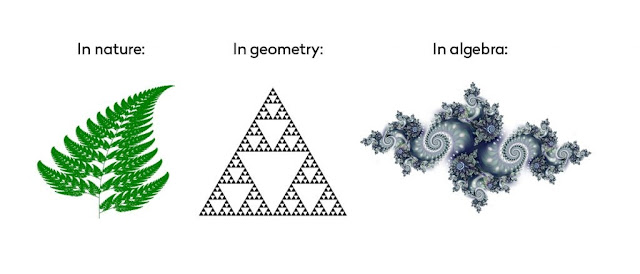

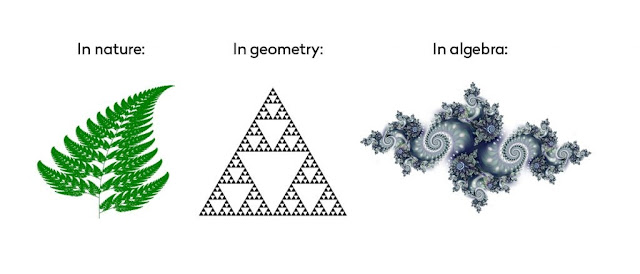

Oliver Sachs suggested that mimicry and choice imply certain conscious intention, imitation is a pronounced psychological and physiological propensity universal to all human biology, all are traceable to instinct. In ‘The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis, Alan Turing suggested how the various patterns of nature, spots stripes etc. could be produced from a common uniform state using reaction-diffusion equations. These equations are an important part of the algebraic family that form fractal geometry (patterns!) and the very basis of the agent-based model is a simple pattern equation known as the cellular automaton. Indeed, if you were to feed a chunk of algebra, let’s say to represent the geometric dimensions of an arbitrary but healthy and fully-formed leaf, into a graphic computer program and press go, a recursive pattern will form, and that pattern would represent the algebraic dimensions of the leaf (5.) These kinds of patterns are considered complex, the automaton, despite its rather complicated name, is a mathematically simplified way to represent complex patterns on a computer.

|

| 5. From nature to Timothy Leary in 3 small steps. |

The patterns of agent diffusion within agent-based models could then be inferred as being

inherently representative of nature, natural process guided simply by the rules that naturally define our daily existence as defined by the automata and the demographics assigned to the agents within the agent-based model. The implications of all this fluff is that agent-based models can provide a good analogue for just that, natural process in addition to acting as an analytical tool to determine factors that may deviate those processes, providing an insight into the possible effects of affecting these processes with attenuating circumstances such as intense urbanisation, varying political climates and resource shortages; all key in the progression of human vulnerability and risk.

In terms of verification, envisage the situation where a flood is impending. You are broadly aware of flood policy and in the immediacy of impending situation you become aware of your neighbours beginning to leave their own homes or locale. Do you ask them why? Do you follow them? If so, why? If not, why not? Whatever your answers to this heavily loaded scenario may be, they will doubtlessly be littered with ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’ and this is fundamentally the obstacle policy faces in trying to ameliorate the fact that it is bound by more ‘ruban rouge’ than the Labour party directive on Brexit, is as apprehensible as the Voynich Manuscript and is as accessible as those two references compounded. Tools are required to test and visualise the compatibility interface between humans and policy before it is implemented. This will diversify and dilute it, making it more accessible; else it will forever be voided by its own hubris and lack of adequate testing. Whether the agent-based model can provide this panacea I am unsure, though one hopes.

An ode

So then, as this ode approaches the twilight of its purpose, having made it through the tour d’horizon of my research and personal interests, turgid with their own bias and logical fallacies (indicated at points, primarily to serve the author’s thirst for poetic liberty) I propose, a middle ground between pessimistic and optimistic bias, to the reader that you might embrace, and consider critically, the bias and fallacy that percolates through the world around you. In a world of climate change denial, where world leaders sharp-shoot their theses to inform decisions that affect us all and where it seems that technology and data has begun to determine our values and worth, it has never been more important to be self-aware and question the legitimacy of apathy for critique.

The ever-prescient Karl Popper suggested in his ‘conjectures and refutations’, that for science to be truly scientific a proposed theory must be refutable, as all theories have the potential to be ‘confirmed’ using the correct arrangement of words and data. It is only through refutation, or transcending the process of refutation, might we truly achieve progressive and beneficial answers to the questions upon which we base our theories. This being a process of empowerment and a sociological by-product of the positive freedom outlined by Erich Fromm. The freedom to progress collective understanding surely outweighs the freedom from fear of critical appraisal for having attempted to do so? à chacun ses goûts, but consider this, in the final verse (7) of his Essay on Man, the final verse he ever wrote, Alexander Pope originally wrote that “One truth is clear, whatever is, is right.” By Popper’s standards, a lot of what ‘is’ today, shouldn’t be and this should ultimately leave us questioning the nature of our freedom, what exactly are we free to and free from? à chacun ses goûts?

‘All nature is but art, unknown to thee;

All chance, direction, which thou canst not see;

All discord, harmony, not understood;

All partial evil, universal good:

And, spite of pride, in erring reason’s spite,

One truth is clear, whatever is, is right?’

7. A section of the tenth (X) verse in the first epistle of Alexander Pope’s unfinished

Essay on Man, (with edited last line for dramatic effect (1733-34.))