It may not be surprising to you that printing the question “Is nuclear green?” on two large banners at the Bristol Harbour Festival in July caused a bit of a stir, but this is exactly what Dr Tom Scott (reader in Nuclear Materials and member of the Cabot Institute at the University of Bristol) and his group of volunteers wanted to do. I joined the group at their stall next to the MShed to listen to their conversations with the public ignited by this thought provoking question.

The volunteers largely comprised of Bristol members of the South West Nuclear Hub (a joint research partnership – which Dr Scott co-directs – with Oxford University), University of Bristol physics undergraduates and some employees of Magnox Ltd a nuclear company in the South West. Together, they rolled out a wide range of activities at their marquee that invited everyone to join in and voice their opinions without judgement.

A live opinion poll with green and red plastic tokens (to vote “yes” and “no” respectively) was placed amongst the crowds along the harbour side to encourage participation and, in general, people were happy to vote publicly. We asked people to explain why they thought that way as they voted: “The sooner that they build Hinkley C the better!” one man announced as he dropped in his green token. (Hinkley C is the name of the new nuclear power station scheduled to be built at Hinkley Point in Somerset.) A red token voter proclaimed “We should go back to coal!” as he dropped his token in. Some members of the public even pretended to scoop up large numbers of tokens to demonstrate the intensity of their view.

|

| Yes/No board to take note of people’s thoughts and feelings about nuclear energy. |

The juxtaposition of the words “nuclear” and “green” in the question “Is Nuclear Green?” suggests that there is no straight-forward answer, but yet intense opinions on the matter persist. Nuclear energy, in general, suffers from a negative public opinion and there are three key reasons for this:

- the perceived risk of the waste product

- the potential for disasters like Chernobyl to happen again

- the historical link between nuclear energy and nuclear weapons.

Dr Scott and his volunteers set about to change public opinion on nuclear energy by presenting the facts on their activities in a neutral light, such that the public would feel free to make up their own minds.

One of the activities at the stall, popular with children, had a Scalextric set (a slot car racing set) connected to a pedal generator – demonstrating how much human power was required to drive the toy cars. Further inside the marquee, you’d see a bucket of coal, 16kg of which is required to meet the electrical demands of one person per day. Many were impressed when they were then presented with a dummy pellet of nuclear waste the size of the end of their thumb that would produce enough energy for their entire lifetime.

|

| This dummy pellet of nuclear waste shows how much nuclear material would be needed to produce enough energy for your entire lifetime. |

Meeting the energy demands of today is a pressing global issue and nuclear power provides a virtually carbon-free way of producing a large quantity of electrical power. Festival-goers were also surprised to learn that due to the large amounts of cement used to install solar and offshore wind power stations, the amount of carbon dioxide released is greater per unit of energy produced than nuclear over the lifetime of the power station.

However, people are generally fearful of the toxicity of waste that nuclear power reactors produce and how it is dealt with. By mimicking Bruce Forsyth’s TV show, Play Your Cards Right, people could learn about the relative radioactivity from different sources. For example, if you went on three transatlantic flights in a year, you would exceed the average annual occupational exposure of a nuclear power station worker.

|

| What gives off the most radioactivity? |

“But what if it all goes wrong?” said one lady from Bristol. This fear is understandable given disasters such as Chernobyl, Three Mile Island and Fukushima and it has resulted in publicly driven change. In Germany, for example, large anti-nuclear protests occurred in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster in March 2011 caused by a tsunami. Partly in response to these protests, the German government have scheduled all nuclear power stations in Germany to be shut down by 2022.

It would be foolish to suggest that the effects of the Fukushima disaster are innocuous and that nothing went wrong. However, it surprised people to learn that despite the large number of fatalities caused by the tsunami directly, there were no recorded fatalities due to short term overexposure of radiation at Fukushima. Of course, the long term effects are unknown and it would be surprising if there were not any future health risks from the disaster.

Many older members of the public were concerned about the connection between nuclear power and nuclear weapons. It is a fact that the idea of using nuclear energy to generate electricity was borne out of the nuclear arms race that started during the Second World War. Nowadays though, the link between nuclear weapons and nuclear energy is unfounded in the UK because the plutonium required to make the weapons is not extracted from nuclear waste reprocessing.

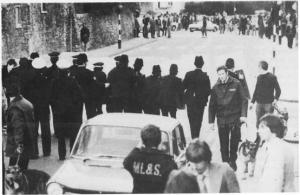

|

| The University of Bristol nuclear research group talking to the public about nuclear energy at the Bristol Harbour Festival. |

The physics of nuclear fission is very well understood by the scientists and engineers working in nuclear energy, and the risks of using this process to generate electricity are met with very strict safety standards. Despite these rigorous safety measures, nuclear power gets a bad press because the evidence for its potential to harm is clearly visible: the waste has to be specially treated before it is buried and the mass evacuations are put into place following a disaster. Nuclear power station disasters are etched into people’s memories because of their scale but the actual risk posed by a nuclear incident is much lower than maintained by the public.

On the other hand, large quantities of greenhouse gases are continuing to be released into the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels and although there is also visible evidence for climate change, the serious threat it poses to our planet it is diluted by politics. This plight is encapsulated by the most solemn of quotes from the event;

“I suppose the truth of it is, that the thing that isn’t green is humanity.”

Perhaps nuclear fission could be a necessary interim energy source before cleaner nuclear fusion takes over in 50-100 years time.

——————————–

This blog is written by Cabot Institute member and PhD student Lewis Roberts.

Read more about nuclear research at the University of Bristol by visiting the Interface Analysis Centre website.