A couple of weeks ago, I was approached by a journalist working for BBC Ouch, the disability branch of BBC News. They had my name on file because of a piece I proposed to write for them last year, concerning how it is possible to be a climate scientist/activist and, at the same time, to be severely physically disabled – not something most people put together. Given that, possibly uniquely, I am very much both of these things, I thought this would be a fairly novel and (I hoped) positive and uplifting piece. Unfortunately, they disagreed, and it never got published. However, they clearly kept my name on file, and approached me several weeks ago asking me to answer some questions, all revolving around the impact of anthropogenic climate change on disabled people. With some hesitancy, which I will explain below, I answered these questions, and the story came out last week; it was entitled “Climate change: Why are disabled people so affected by the climate crisis?”.

As I said, I approached the questions with more than a little hesitancy, because I am very much not a disabled activist and have never really let my physical issues be a big deal. Let there be no misunderstanding – I care very much about the issues of disabled people, but the subject does not dominate my existence and I strongly object to the (surprisingly common) attitude that it somehow should. How racist would it be to show raised eyebrows when learning that a person of colour was not attending a Black Lives Matter protest, implying somehow that they should? But I have received the equivalent reaction many times. With that in mind, I was hesitant to answer the journalist’s questions, all the more so because it became immediately obvious that the agenda was the one described above i.e. it was focusing purely on how badly off all disabled people are, and that anthropogenic climate change is just another example of this. Of course, it is very true that many disabled people are indeed suffering greatly, for a number of reasons; but that is not true for everybody, and in my opinion is not a generalisation that should be made.

Moreover, as I explained to the journalist, what I wrote for them was not based on any in-depth scientific evidence or research. What I wrote, and indeed what I now write below, was and is therefore only be treated as personal opinion and some conjecture on my behalf. Likewise, I cannot possibly speak for all disabled people, because the needs and challenges of someone who is visually impaired are completely different to those of someone who is hearing impaired, or in a wheelchair. Moreover, as a caveat, most of my comments below relate to those people with a physical disability, as I have little experience with people with a learning or emotional disability. Clearly, if somebody does not have the capacity to do everyday tasks, no-one would say they should be doing more to tackle anthropogenic climate change. This is why, in general, I do not like the word ‘disability’, because it is incredibly broad and covers an enormous range of issues. Unfortunately, being disabled does not give me a magic clairvoyance to understand other disabled people! I can, of course, sympathise and empathise, and I can hypothesise over the possible challenges, but with only as much authority as any other member of the public. Sadly, I don’t have any special insight.

Therefore, although I answered the questions to the best of my ability, the main thrust of my argument was different to what they clearly wanted. In short, I argued that firstly everybody (not just disabled people) is going to be impacted by anthropogenic climate change, and secondly that the economically vulnerable will be disproportionately hardest hit. Given that, for a variety of reasons, disabled people are often amongst the most economically vulnerable, this is why they will be amongst the hardest-hit. So my argument is that disabled people will not necessarily be hardest-hit because of their disability (although there are some examples, discussed below), but rather because of their economic status; which is exactly the same for many other people, disabled or not, in the same economically vulnerable group.

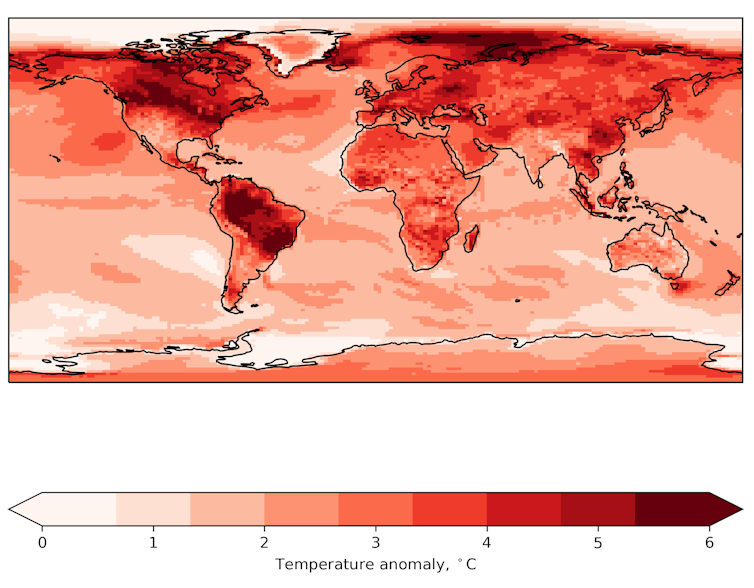

To elaborate, my argument is that everybody is going to be hard hit by anthropogenic climate change, in many different ways, but that probably the most important thing concerning how hard an individual feels the impacts of climate change is their financial situation. This is the case at both the international level (e.g. developing countries will be harder hit than developed ones, simply because the latter can afford to adapt to the impacts), and the individual level. In other words, those individuals that are financially stable and secure will be much better placed to adapt to the impacts of anthropogenic climate change, and will therefore be relatively less hard-hit. Unfortunately, it is often the case that disabled people are not in this financially secure position. This may be because of a number of reasons, such as either being unable to work because of their disability or being unable to find a job because of rampant (but well-disguised) discrimination. According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), during the year October-December 2020, 53.6% of the 8.4 million disabled people of working age in the UK were in employment, compared to 81.7% of those who are not disabled1. Likewise, the unemployment rate for disabled people was 8.4% during that period, compared to 4.6% for non-disabled people1. So more or less twice as high. As a result, during the same period 42.9% of disabled people were considered to be economically inactive, compared to only 14.9% of non-disabled people1. This may be because of a lack of education; again according to the ONS, the employment gap between disabled and non-disabled people with no qualifications is 41%, but this decreases as the level of education increases (it is only 15% for those with a degree or equivalent)1. So I would argue that it is a multifactorial process; with possibly a lack of education, resulting in a lack of employment, resulting in a lack of financial security, being the main reason why disabled people will be amongst the hardest-hit.

After the question “Why are disabled people hardest-hit?”, I was then asked how and in what ways, and what might happen in the future. To quote some recent research, disabled people will be hit in the same way as anybody else, but simply harder2. This I don’t dispute. The example given in that particular piece of research is that of a hurricane, where a disabled person might need more social and medical support that someone without disabilities2. We know that anthropogenic climate change has already increased the intensity of observed precipitation, winds and sea level changes associated with tropical cyclones3, and this is only likely to continue into the future. Another example, perhaps more relevant to the UK, is severe flooding. We have recently seen on the news, across Europe and in the UK, many images of houses and even entire streets being inundated due to extreme rainfall events causing flash flooding, and this is going to impact disabled people more than others in very physical ways; as a wheelchair user, I for example would not be able to get into a rubber dinghy to be evacuated. There are many other examples of where there may be other, very severe complications for disabled people. For example, disabled people may well have lots of equipment in their homes which, if the home was to be flooded, might be badly damaged; this is not just everyday equipment such as TVs, but rather some of this equipment might be critically needed for survival, such as ventilators or oxygen concentrators. Another example, which is discussed in detail in the BBC article and was also highlighted by the other expert they interviewed, is extreme weather

events, either heatwaves or cold snaps. Again, this is a generalisation, but many disabled people are more sensitive to extremely hot weather, which can often exacerbate existing conditions4. The only way to avoid problems with our rising temperatures would be to install air conditioning units, which are expensive and again brings us back to the financial security argument. The same is true for cold weather, with many disabled people suffering greatly during very severe cold spells, again due to existing conditions (e.g. joint pain) being exacerbated. Again, the only way to avoid problems here is to increase the level of heating, which again has financial implications. We know that, as well as a general rise in temperatures, in the UK we are going to see an increase in extreme weather events, both hot and cold, and therefore the above problems are only likely to get worse5.

Finally, after the what, why and how, I was asked what needs to happen and whether I believe disabled people should be more involved in the fight against anthropogenic climate change. As I explained to the journalist, I need to be a bit careful in answering these questions, because I see my role as a Climate Scientist as not to be preachy and tell people what they SHOULD be doing, but rather to be scientific and tell people what they COULD be doing. It is then up to the individual to decide whether or not to take any action. Some Climate Scientists do not agree with this attitude, arguing that we should be preaching the good message, and I respect this way of thinking. But I do not share it.

With that in mind, although I believe everybody can take some personal responsibility for tackling anthropogenic climate change, ultimately the problem is only going to be solved at the international level. This of course means governmental action, working together globally across multiple countries and continents. Governmental action is starting to happen, with the first concrete pledges coming from the Paris Agreement in 2015 and, at the time of writing, COP26 being in full-swing in Glasgow; so far signs are positive with, for example, a pledge to end all deforestation by 2030. But it needs to go further. More extensive governmental action is only going to happen if there is enough public pressure from the people that elect those governments. As individuals, I believe that the best thing we can do to help this is simply to

talk about it; to understand it, to bring it into our everyday lives and conversations, and to get involved in lobbying both local businesses and (possibly more remote) government institutions. To use the dietary argument (discussed below), supermarkets are only going to keep stocking meat and fish as long as there is a public demand for it. Banks and businesses are only going to invest in fossil fuel companies whilst they have customers; if their customers go elsewhere, to more environmentally-friendly competitors, things will change.

To answer the question over whether I believe disabled people should be more involved in the fight against anthropogenic climate change: I don’t just believe disabled people need to be more involved, I believe EVERYBODY needs to be more involved! I believe that everybody can do something, if the motivation is there. I completely appreciate that disabled people often have lots of much more pressing matters, and these should absolutely not be trivialised. Many disabled people might well argue that they cannot possibly worry about anthropogenic climate change given their own challenges and issues, and for them that might be true. But it is not a universal law. That being said, I do accept that when it comes to policy and structural reform, there is a danger that minority groups such as the disabled are ignored or (more likely) simply forgotten about; the case of plastic straws, mentioned in the BBC article, is a classic example of where this happened. The only way to avoid this is for disabled people to be more involved in the decision-making process from the beginning, not included as an afterthought.

So what can individuals, including disabled people, do on a personal level to tackle anthropogenic climate change? The standard list of things to do is fairly well publicised these days, but given that this piece is about disabled people I will frame some of the answers within that context. I will also give some examples of what I do on a personal basis but, to stress what I said above, I am not arguing that anybody SHOULD do these things.

Firstly, people can cut down on transport, and in particular flying and the use of cars. Concerning disabled people, and in particular wheelchair users, air travel is and has always been extremely challenging anyway, so may not be much of an issue. But it is certainly something to think about. For myself, I am lucky enough that I am able to use air travel (although it is far from easy), and historically have flown all over the world for both work and pleasure. These days I am acutely aware of the hypocrisy of this, and have therefore cut down massively; I will never again take any domestic flight, and will allow myself international air travel very infrequently and only when absolutely necessary. On these occasions, I will attempt to offset my carbon emissions by donating to one of the many green projects and programmes that are now available; this, of course, requires some level of financial security, which I am blessed enough to have. In terms of cutting down the use of cars, this is probably going to be one of the biggest problems for many disabled people (certainly myself) because public transport is generally very inaccessible. Things have improved over the years but nowhere near enough, especially for example in the London Underground. Therefore my car is the only option. Many disabled people with cars, including myself, use the Motability scheme6, and whilst this is generally brilliant, there are currently no electric or hybrid wheelchair accessible vehicles (WAVs) available using the scheme. Even if an electric or hybrid WAV was available, it would undoubtedly be very expensive, which brings us back to the financial security argument again. Likewise, the advice of leaving your car at home and cycling to work is probably not very useful to many disabled people!

Secondly, people can make changes around their home, such as improving insulation, installing solar panels, or switching to an environmentally-friendly carbon-neutral energy company. Again, it is often not so much the disability that is stopping people from doing any of these, but rather the cost. All of these things are expensive, some (such as installing solar panels) more than others. Given that, as discussed above, disabled people are often in the economically vulnerable category, these may not be viable, but if they can be afforded then they could be considered. For myself, I live in a ground-floor apartment by the river (therefore potentially vulnerable to flooding!), with my block externally managed by an agent, and therefore have no control over things like insulation or installing solar panels. I am, however, lucky enough to be financially comfortable, and therefore I use a more expensive but 100% carbon-neutral energy company.

Thirdly, people can make changes concerning their shopping, recycling and dietary habits. Again, there is a financial element here, because for example buying organic food is undoubtedly more expensive, and therefore this may not be viable for those who are economically vulnerable. Online food shopping has becoming increasingly popular, with most supermarket chains now offering deliveries, and (again conjecture) this is something many disabled people undoubtedly benefit from; the downside of this is that there is always a lot of plastic involved in whatever is delivered, whereas someone able to go to the supermarket would be able to choose loose fruit and so on. But there are ways around this, the main supermarkets are slowly improving, and there are more independent companies now that deliver environmentally-friendly groceries and food. So, as before, if it can be afforded, things like buying organic and cutting out plastic could be considered. For myself, I use an independent company that delivers local, organic, sustainable and environmentally-friendly groceries, delivered either in compostable bags or brown paper bags; undoubtedly, this is more expensive, but I am fortunate enough to be able to meet this cost. Likewise, when it comes to recycling, this is something that everybody can do, regardless of being disabled or not. If a person is able to throw something in the bin, they are able to put it in the recycling bin (where appropriate). If they are not able to throw something away themselves, because of a disability, then it is hopeful that they have someone to do it for them, be that a friend, family member or official carer. That person can therefore use the recycling bin. Personally, I recycle absolutely everything, and have a composter in my small garden for anything that can go in it.

Finally, and probably the most controversial one in this category: changing dietary habits. I am not going to argue that everybody should be vegetarian or vegan; especially for many disabled people, who have very specific diets and would not be able to cut out the protein and vitamins included in meat, fish and dairy, this would not be possible. Physical health and how it relates to diet should be one of the more important priorities for any individual, disabled or not, therefore there should be no blanket advice. However, if an individual (disabled or not) is able to reduce their meat consumption, especially red meat such as beef and lamb, even if only two or three days a week, then that is something that could be considered. In the UK, only a 20% reduction of meat consumption, as well as a 20% reduction in agricultural land being taken out of meat production, is needed to reach our CO2 net zero target by 20507; based on a working week, this is only one meat-free day per week. For me, I used to be an ardent meat eater, not because of disability issues but because I enjoyed it; however, over the last 10 years or so, I have been cutting down dramatically and, as of last year, I am now almost completely vegetarian and, many days of the week, vegan.

Lastly, as discussed above, probably the most important thing that everybody can do, disabled or otherwise, is to simply talk about anthropogenic climate change and get involved in tackling it in some, even little, way. I am not arguing that everybody needs to be an expert or even have a deep understanding of the subject, but even a mild interest is a step in the right direction. For everybody able to, getting involved, even in a small way, is something that can be done by all, including disabled people. It does not have to involve going on marches, blocking motorways or gluing oneself to railings, which many disabled people (including myself) would not be able to do physically. But it can involve talking to people (such as friends and family members), talking about it on social media, and joining climate-related groups; the latter, in particular, has become easier since the COVID pandemic, with virtual meetings now commonplace, something which is much easier for many disabled people if they struggle to leave their home.

To end this post with some positivity, and indeed the way I ended what I wrote for the journalist, I believe there are many good reasons to be hopeful when it comes to tackling anthropogenic climate change, whoever the individual is and whether or not they have a disability. The ways of doing what needs to be done are well understood, and the science is clear on how to do things like Carbon Capture and Storage or how to reduce our carbon footprint on an individual level. The problem, and the concern, is the apparent lack of motivation and willpower to do these things, both at the individual and political level. Unfortunately many of the above things that individuals can do will involve a loss of some sort (be it financial, social or personal lifestyle changes) and many people, such as those with disabilities, may not be able to manage that loss. Only time will tell if these attitudes will change; there has certainly been a dramatic shift in the last ten years, but this needs to continue. At the political level, meetings such as COP26 will be vitally important, but again only time will tell if these result in actual action or just more discussion.

References

1Powell, A. (2021). ‘Disabled people in employment’. House of Commons Library,

UK Parliament. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7540/CBP-7540.pdf. Accessed 16/10/21.

2Liebmann, D. (2021). ‘The Intersection of Disability and Climate Change’. Harvard Graduate School of Education.

https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/21/03/intersection-disability-and-climate-change. Accessed 16/10/21.

3Collins M., M. Sutherland, L. Bouwer, S.-M. Cheong, T. Frölicher, H. Jacot Des Combes, M. Koll Roxy, I. Losada, K. McInnes, B. Ratter, E. Rivera-Arriaga, R.D. Susanto, D. Swingedouw, and L. Tibig (2019). ‘Extremes, Abrupt Changes and Managing Risk’. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/3/2019/11/10_SROCC_Ch06_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 16/10/21.

4Harrington, S. (2019). ‘How Extreme Weather Threatens People with Disabilities’. Scientific American.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-extreme-weather-threatens-people-with-disabilities/. Accessed 16/10/21.

5UK Met Office (2021). ‘Effects of climate change’.

https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/climate-change/effects-of-climate-change.

Accessed 16/10/21.

6https://www.motability.co.uk/. Accessed 16/10/21.

7The Lancet Planetary Health (2019). ‘More than a diet’. https://www.thelancet.co

————————

This blog is written by Cabot Institute for the Environment member Dr Charlie JR Williams BA DPhil FRGS, Climate Scientist and Research Fellow in the School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol as part of our COP26 blog series. You can follow Charlie on Twitter at @charliejrwill.

|

| Dr Charlie Williams |

Read all blogs in our COP26 blog series: