When describing the commercial port land of Felixstowe (fig. I) as a ‘nerve ganglion of capitalism’ in 2006, a proto-nostalgic horizon ‘blighted by cargo ships’, Mark Fisher was describing a vision of the natural’s collision course with the monetary in words that ooze forth from the ascetic expanse he walked us through, right up to the journey’s reposeful end point, the burial ground at Sutton Hoo (fig. II). Here, in this space, palpable is the sense that the increasingly unseen in today’s world is seen so lucidly that upon listening closer, Beowulf’s verses may come rushing forth upon the Deben mists to play amongst the ancient mounds and time-worn grasses.

|

| Figures I (top) & II (bottom): Felixstowe container port (top) the largest of its kind in the United Kingdom, a point of arrival and nerve ganglion of capitalism responsible for the distribution of material commodities across the land along established networks of commerce. By contrast, the ‘sunlit planetary quality of serenity’ offered at Sutton Hoo (bottom) engages with a vision of departure, two different points within a geography that speaks to themes of migration, mobility, and the conflict of boundary in space and time. (sources: Institution of Civil Engineers (top) & thesuffolkcoast.co.uk (bottom)). |

In a space as innately human as this, the purpose of the city, the urban, and what it means to exist in it becomes overwritten in the victorious verse and rhythm of nature and the environment, yet there is an eeriness inherent in this vision. A sense of disconnection and immobility that is increasingly disassociated with the ever-expanding urban centres across the world. This is a sense that many might argue is, itself, becoming increasingly overwritten through development and, possibly more directly, through proliferating networks of digital visualisation and communication.

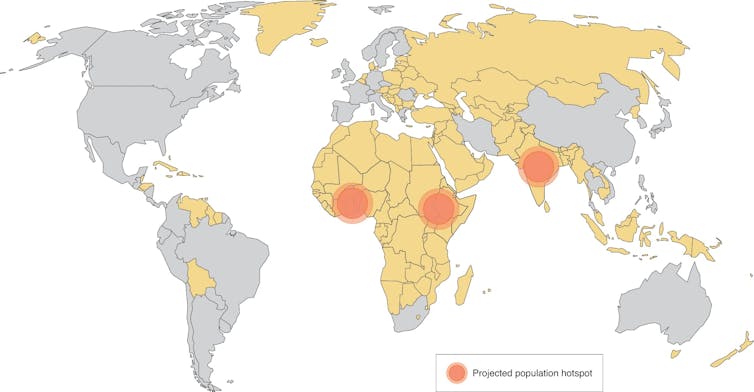

More of us are living in urban settings and more of us are moving to them, what drives this flight to the city, the deeper motivations can only be described as, much like the conditions of the British weather, myriad. What this mobilisation and migration looks like is relatively more straight forward to describe: a need for access to resources through labour, coupled with a space in which to live and be at home, to rest. Mirrored perfectly in Fisher’s visions from Felixstowe to Sutton Hoo, a seamless cross section of the Anthropocene. Capturing the stillness afforded by a space so radically different to the city, where the scale of achievement, to simply occupy a space with as much concrete matter as is condensed into the wondrous square miles of London, Birmingham, and Manchester, amongst many others, by comparison to that which does not occupy the vastness of Suffolk is astonishing. Historically, progress for those who have settled in these cityscapes has, in many senses, been assured, simply through an increased likelihood of encountering streams of revenue and capital, or so goes the utopian visions of the upwardly mobile Mondeo Men and Worcester Women.

Loosely this might be described as the enabling of capital progress, however these connections, patterns and trends underpinning, however loosely, such stereotypical visions of city living have become much more distant for most within the current global climate. A crude utilisation of Tobler’s first law of geography would, when coupled with Mark Fisher’s nerve ganglion metaphor, lead us to deduce that those closest to capital, to the contemporary capital markets of the city, are not as readily likely to benefit from this proximity as they might once have. This sense of capital mobility associated with the city is now fundamentally more precarious and is visually very different from that seen in the past, offering the first glimpse of the landscape of risk.

Of course, this form of mobility is not completely linear as the city has long also been associated with a flux of capital mobility represented by a great, and growing, disparity between those operating at the top of the metropolitan hierarchy, in gleaming beglassed monoliths, and those looking up at them from the mosaic of avenues and streets below. This structural and spatial inequality of the cityscape is as symbolic of the urban as it is of the human condition it embodies, where products of value are exchanged for labour and where, as David Harvey explained in Social Justice and The City, ‘capitalism annihilates space to ensure its own reproduction.’ Historically facilitated by barbaric internal mechanisms in the West, from blockbusting and redlining amongst a spectrum of variable living standards that extend from unthinkable to the decadent, urbanisation and urban expansion reassembling the natural spaces in the pursuit of capital will naturally enhance and further facilitate the growth of inequity and thus, further strengthen the boundaries of the risk landscape.

This does come down to a fundamental connection between capital and risk, where risk is largely framed in the context of ‘asset loss’ but the landscape in which it is most acutely observed, where capital value is most apparent, the city, is where it is, and will continue to be, predominant. Harvey concludes his vision on the engagement with political process as fundamental to traversing the forms of inequality and injustice generated and facilitated through ties to this form of ‘development’. Consequent of the unprecedented recent times we have lived in, and now continue to live through, together, the public inquisitions regarding the moral constitution of those responsible for overseeing political processes challenges any desire for engagement. Age old theoretical undercoats of societal constitution and modernity begin to peel away under the searing heat of growing public discontent whilst those at the very zenith continue to profit financially.

The risk landscape is one fraught with conflict and is perpetually in crisis. However, were this crisis to be wholly one of capital, it would affect everyone. Capital and inequity are one facet of the greater conflict the risk landscape has with the environment at large, as even when this crisis is framed in the context of equity, it finds equilibrium in the continuation of the trend that, depending on where you are categorised within the social hierarchy of the city, you will continue to be worse off from here on out and no amount of ‘levelling up’ will bring about a truly positive change to this course. We are beginning to feel this at home, on a personal scale now through a volatile geopolitical landscape, but that doesn’t mean that labour is any less abundant. The boundaries of the risk landscape will continue to expand beyond this and find a continuing but ultimately existential conflict with the natural environment, generating an accelerated form of risk that is much more linear in outcome. The general message related to this is clear: ‘Adaptation of current modes and systems to emergent environmental risk is needed, with further mitigation required to prevent the acceleration of this risk’

The modern human age is liquid, where change and continuity are seen to different degrees and operate at various tempos across time. Were I to define which of the processes discussed throughout this missive are representative of change and continuity, I would posit that the ultimate defining factor of both lie in the hands of nature and not my own. Whilst social categories become redefined through mechanisms closely tied to the city, overwriting of old landscape structures through the proliferation of the urban over time generates a legacy of risk through reparation and over expansion. In appropriating space that is not in the interest of that which inhabits that space, be it the development of floodplains to accommodate homes, the utilisation, or lack, of land due to pollution from past industry, processes of land reclamation, we are clutching at straws. Yet, capital is generated and claimed with little interest for the longevity or safety of those inhabiting these new spaces, asserting a dynamic of equitability for whom exactly?

It is in this dissection of value, it’s definition and by whom (or what), that the vision of the risk landscape becomes truly material. How these values shift, and to what benefit, must continue to be explored if we are to make a sustainable vision of the city into a liveable environment, equitable for all who will call it home. If our mobility within this exploration could be versed in the cognitive, as Mark Fisher did for us, then we are becoming more aware of the trends that connect the naturally seen and unseen with the landscape of risk. Supporting us in the delineation of what is really of and for us against that which appears to be, revealing what it is to be truly of and for the natural.

—————————-

This blog is written by Cabot Institute for the Environment member, Dr. Thomas O’Shea. Dr O’Shea is a postdoctoral research associate with the University of Bristol School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies. The primary focus of his research is on developing understanding of the human-water interface with specific interests in the application of social theory, urban and hybrid geographies towards shaping narratives and strategies of sustainability.

This blog is the final blog in the Migration, Mobilities and the Environment blog series, in conjunction with Migration Mobilities Bristol.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)