Political polarization, the ever-widening divide between Right and Left in the US, is an obvious problem. We have lost our ability to communicate with one another: using different sets of ‘facts’ to back up our arguments, with the ‘facts’ depending on our side of the political spectrum. The internet has in large part facilitated this fracturing. One can spend 10 minutes on Google to find support for anything that they believe. For example, Youtube videos link to increasingly conspiratorial videos, pushing us farther apart. This loss to our collective conversation is damaging in most arenas, even in the classroom or lecture halls. When a collection of outright lies masquerading as facts meets science, it causes problems. When a student population has firmly-held beliefs in concepts that are simply not true, as a facet of their personal values or beliefs, this presents a difficult and unique challenge for an instructor. I was a visiting assistant professor in a conservative area, dealt with these issues, and hope to provide some help for those who are walking into a similar task in this post.

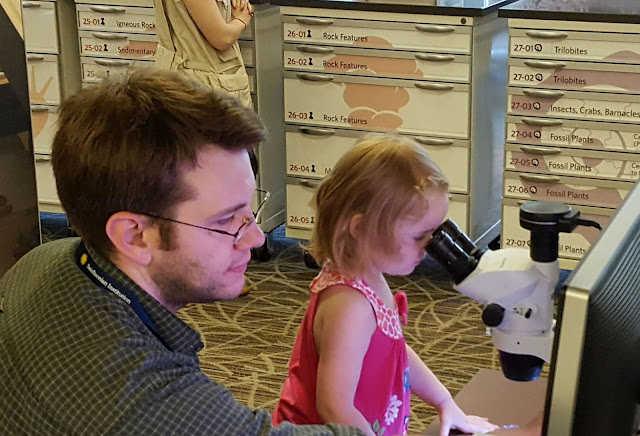

I loved teaching at Sam Houston State University (SHSU), enjoyed my time with both my students and colleagues. Some of this is going to read as if I was combative the entire time I was at SHSU. I wasn’t. I truly enjoyed interacting with my students (and most liked interacting with me, from reading my evaluations), especially the ones who thought about topics differently than I do. College is supposed to be about exposure to new ideas, after all. I find it difficult to let people believe in materially incorrect things however, especially when they’re detrimental to their lives, and to my own or my family’s lives. SHSU is in a very conservative area in East Texas, and my introductory, general education course covered both climate change and evolution. Covering these subjects meant that the students signing up for “Historical Geology” as an easy science credit got a more ‘controversial’ course than they expected.

To say that climate change or evolution is controversial is imprecise. Both subjects, scientifically, are not controversial, especially at the introductory level. Evolution is a multifaceted theory that is accepted by scientists and there are no competing arguments; this has been understood for 150 years. Scientists also agree that the climate has been changing for decades, and that carbon dioxide (CO2) is a potent greenhouse gas since Svante Arrhenius calculated the extent to which increases in CO2 can cause heating in the atmosphere (he was alive in 1859-1927). Both subjects, unfortunately, are controversial in the public’s eye. Today, 29% of the American public believe scientists do not agree that humans have evolved over time, and 32% reject the scientific fact that is human-caused climate change (and 24% are uncertain!). Walker County, TX, which SHSU is in, has 7% lower acceptance rate than the national average. When I asked my students if scientists agree or do not agree that evolution is a fundamental process describing change through time, ~20% said scientists did not agree. To say that my classes were comprised of more conservative students, with strong personal beliefs, than an average introductory science course in the US is probably accurate.

Teaching these particular students about climate change isn’t simply because it’s course material–it’s vital for them specifically. My second week of teaching was canceled entirely by the university because of the impact to the region by Hurricane Harvey. SHSU is a 45 minute drive from Houston, and areas of the town were closed. Many students were commuting from the south, and some had to miss additional classroom time. One individual had to miss many Fridays that semester because he was working on fixing his mother’s house. Climate change has a direct impact on that region, will continue to have a direct impact, and these students should be fully cognizant of their choices when acting as consumers or citizens. There is an irony to a region economically-driven by oil production reaping the consequences of climate change. That, however, doesn’t mean that the population should suffer.

|

| Flooding in Houston, Texas caused by Hurricane Harvey in 2017. The hurricane caused unprecedented flooding which displaced 30,000 people from their homes, causing more than $125 billion in damages. Image credit: urban.houstonian. |

Educating a student population with strongly held personal beliefs counter to course material doesn’t work well with traditional teaching methods. We not only have to teach students the material that they need them to understand for the course (past greenhouse gas changes, radiative forcing, proxy data, feedback mechanisms, etc.) but we also have to convince them of barefaced reality. We have to convince them that, no, scientists aren’t lying to them or the public. We have to convince them that we’re not in the pocket of ‘big-environment’, reaping the benefits of ‘big’ grants. We have to recover their idea that there can be legitimacy of the scientific process. If you say the words ‘climate change’ to someone of a Right ideology, they are likely to not listen to what you say afterwards because you’ve been written off as ‘far-Left’. How do you teach when your students might react that way?

A Hybrid Teaching Approach

Instructors, professors, and educators have to engage in science communication rather than teaching. Not entirely, but to a degree that can be uncomfortable. To explain: Science communication is sharing scientific results with the non-expert public. It relies heavily on a ‘values-based’ model, which is empirically more effective than the older ‘information-deficit’ model. The information-deficit model said that “People just don’t know enough, so if I explain what I know, they’ll agree with me.” That’s standard teaching. The professor explains the subject, the students take notes, everybody agrees the professor is telling the truth and that the professor has the most thorough understanding and information. The information-deficit model assumes that facts win, which simply isn’t the case. We resist facts that don’t conform to our strongly held beliefs. It doesn’t work if everyone does not agrees that the professor has authority in the subject. If a large enough number of the class think the professor is a member of a global conspiracy of attempted wealth redistribution, then the information deficit model falls completely apart. If the information-deficit model worked, then no one walking out of a (properly taught) high school biology course would believe intelligent design or creationism. That’s simply not the case.

The values-model says that the communicator (professor, instructor, educator) establishes shared values with their audience and communicates with them in a back-and-forth exchange. They then explain why a scientific concept is important to them, and why it should also be important for those who share the same values. That’s not teaching, in the purest sense, because it’s broader than just pure information conveying. That’s also not possible in the lectures we frequently find ourselves teaching.

Let’s assume that our goal is to take students who are uncertain about climate change, or don’t believe that evolution has occurred through time, and get them to accept scientific truths. Information-deficit isn’t going to get us to students accepting the truth, if we’re dealing with a resistant population. While not all of my students were resistant, I like to ‘swing for the fences’ and get everybody to understand concepts. Past students said they liked the ‘nobody left behind’ classroom ethos I set out. The values-model is uncomfortable for scientists, in particular. A scientific-upbringing, like one has while you get a Ph.D., prizes the ultra-rational and eschews ‘values’ for data (click here for a discussion about science being inherently political).

Blending both the values-based and information-deficit models of teaching might be the right approach. We need to communicate information, but if we demonstrate to students why the subject matters, how it fits with their previously held ideas, or even provide space for them to blend their faith with known biology, then we move them away from irrational, ill-placed skepticism.

I had these concepts gnawing at the back of my head while I was teaching my introductory course (Historical Geology). There was one particular moment that help me see a blending as the correct way forward. In class I occasionally asked students to submit anonymous questions to me on note cards about either impending or just-covered subject material. I’m one of the only research-centric scientists these students might ever meet, and I know from conversations with students that they have questions that weren’t covered in the course. Sometimes I answered the note card questions in lecture alongside the regular material, like in my climate lectures. Other times they exchanged cards with 5 other people, then the last person decided if they wanted to ask that now-anonymous question right then. At the end of my evolution section I got the question “What are your values?” from a student. I used my answer to that question as my first slide when discussing climate change.

That’s me sharing a value that most folks should share: that truth is important, something that we should respect. I used it to set the stage for a series of lectures on climate change that talks primarily about the mechanism and past examples, but also talked about climate models, future projections, and why we’re still arguing about it.

The following are my suggestions for how to teach a subject that folks in your classes think is controversial.

Basic structure

I opted for an overt structure to the roughly two weeks that I discussed climate change. I went methodically through a series of questions, going from “What can change climate?” to “Has climate changed in the past?” and “Why might it matter?”. Touching back to the objections that folks have to climate change and systematically explaining why they are wrong is useful, and makes a really compelling way to organize your lectures. Just be sure not to reinforce the incorrect material by stating it as a statement, rather phrase them as questions. So, you shouldn’t say things like “‘Climate changes all the time, so it doesn’t matter if it does now’ is wrong”, instead it should be “Has climate changed in the past? Yes, but here’s why that’s important”.

Spend time with contrarian ‘evidence’

I had a student bring up a conspiracy theory: the Rothschilds were funding research in climate change and if the research came up counter to human-caused climate change they’d bury it. The student then brought up a ‘fact’ which I’d never encountered before, which they said had been buried by the Rothschilds company. The fact was counter to a huge amount of real research. All I was able to do in the moment was to explain the way things really are, but if the student has decided that the underlying data is falsified it’s difficult to counter. Since then, all I’ve been able to find is an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory from the Napoleonic Wars and a Democratic DC Council member talking about how the Rothschilds control the weather. I still do not know where the student got their ‘fact’. I feel like I was under prepared to handle that interaction.

The index card activity that I mentioned above allowed me time to prep for these kinds of questions from my students, when I ask them for questions for the next lecture. I prompt them with “What’s a question that you’ve always wanted to ask a climate scientist? Something you heard about that sounds wrong or is confusing?”. On the spot, it’s difficult to do the due-diligence of tracking down the source of the student’s misconception. A student in another class wrote a question about Al Gore’s prediction of a sea-ice free Arctic Ocean by a certain deadline. The student missed several key points; it was about Arctic summer ice, Gore is not a scientist, the actual analysis Gore got that from was correct, Gore just used the most pessimistic number rather than the scientists preferred value, etc. Those aren’t facts I keep in my head, but I was able to collate them and present them one-after-the-other as a way to dismantle that piece of misinformation.

One way to view the interactions is as an accidental “Gish Gallop”. Dwayne T. Gish was a debater of evolutionary biologists. He was infamous for his rapid-fire objections to evolutionary science. He would place a simple objection, “There are no transitional forms,” and then another and another, then the scientist would need to explain why that’s clearly not true. The explanation requires a great deal more time. Any unanswered objection is then assumed by the audience to be correct. Such is the way in these classes. If you don’t clarify or correct a student’s point, that point is assumed to be correct, at least by the students you’re trying to reach the most, the ones that don’t accept the legitimacy of climate or evolutionary science.

In an ideal world a student would say, “Did you know crazy-thing-X?” and you respond, “I saw that somewhere, but that’s completely wrong because of A-B-C-D, and have you considered that person-backing-X does so because of E-F-G?”. It’s easier to catch something out of left field if you have some knowledge of the outfield.

Consider your approach

Telling somebody to their face that they’re an idiot for voting for somebody might be both cathartic and true sometimes, but it’s not that effective. Changing minds doesn’t involve hurling epithets, even if the president and his supporters are doing it (please see section My Perspective below for an important caveat). Scientists have facts on our side. Proving your point without literally cursing the name of the current president during a lecture in class is more effective than adding “*&@^ Trump”. Are you just venting your own frustration or are you trying to actively convince these folks who are wrong to join the correct side? By all means, force your students to grapple with the underlying long-term consequences of their voting choices, if they voted for him, but do it in the most effective way possible. Yelling at them is just going to stop them from listening.

An example: three students and I are having a conversation that explicitly turns to voting for Trump*. One student voted for Trump because Trump was going to redistribute wealth to the little guy, the other voted for Trump because Trump was going to engage in trickle-down economics (a failed style of economic policy that gives taxes breaks to the ultra-wealthy that then increases economic benefit down the class structure [it fundamentally does not work]). I tried to make sure they realized that they voted for him for polar opposite reasons, and that at least one of them had to be wrong about what Trump would do in office. Just like we try to do in education: making them walk down the path themselves, providing a guiding hand when necessary, and not just telling them, is more effective than yelling it at them (I’ll admit I laughed at the idea that trickle-down economics would actually be effective, but it took me by surprise).

I also spent a lot of time thinking about how the students perceived me as the messenger. I am originally from the Northern Midwest, where “hey guys” is a gender-nonspecific greeting for a group. In Texas it’s “y’all”, which is actually gender-nonspecific, unlike guys which is just used as nonspecific while being male. It’s very easy to adopt regionalisms accidentally or when it appeals to you for good reason. I’m living in the UK now and I’ve no reason to start saying trousers but I have. I fought the “y’all” change because it felt like the students would perceive me trying to co-opt their language to be more like them, which if you add me trying to push them away from strongly held viewpoints, would lead to resentment.

*This happened without me trying to get the conversation there. I try to discuss the political issues with my students, not the individuals involved in politics, when possible.

Talk politics

One of the questions that stuck out in my mind most from the folks who already accepted and had seemed like they might have a solid understanding of climate change was “Why do some people not believe in climate change?”.

Besides the word ‘believe’ in there, it’s a really astute question. Why is it? The physical basis is solid and fairly simple. The question ends up being more of a social science question. Leaving that unanswered though, falls into a serious trap. If you’re presenting the physical science of climate change you leave questions in your students’ minds. They know there’s another side to the ‘debate’. While the ‘there are two sides to every story’ journalism trope has plenty of faults, we’re conditioned to expect to hear the other side’s opinions. So cover it! Without it you seem like you’re trying to obfuscate.

Explain how the Pope, the U.S. Department of Defense, and all oil companies have statements affirming that climate change is real. Go to Open Secrets and show them where the lobbying money goes (mostly Republicans, with the occasional Democrat from an Oil state like North Dakota). Talk about the fight to remove lead from gasoline (which has a great connection to the age of the Earth), or talk about cancer and tobacco litigation. I also try to explain to students about the Dunning-Kruger effect and how confident non-experts can be when discussing topics (which explains the bulk of the internet). Explain how you can simply say the words “Climate change” to someone on the right and they erect a mental wall, not hearing anything after. Explain that the divide on climate change acceptance can be attributed strongly to political party. It is scientifically shown that climate change is a a political issue . By ducking the question you’re doing a disservice to your students.

Judging pseudo-scientific crap (fact checking?)

A basic understanding of how to engage in sniffing out pseudoscience is useful these days. There are folks peddling all sorts of incorrect information, and students should be inoculated to that. It’s certainly relevant to climate change, where on social media stories about how climate change is all faked go viral very quickly. Giving students a primer on how to suss out lies, misinformation, and disinformation is important in your class and literally every other!

Individual actions vs. community actions

Lastly, while this might lose your conservative students, it’s important to discuss with your students the actions that can be taken. While individual actions are useful and important, we all have our roles to play in conservation, those individual actions aren’t going to solve anything by themselves. The issue in climate change isn’t solved by one, two, or a hundred people starting to recycle (though that is a good end), it’s systemic change that is required to fix this problem. The end goal of doing this is to motivate the students to vote or to engage with their policy makers in some fashion. Them driving less is important, but the impact is not of the magnitude that we need.

I’m deeply uncomfortable with advocating for individual solutions. As a physical scientist teaching a physical science course at a public institution, it’s not really my purview to go into what solutions are politically feasible, unless asked. I explain the situation, I go through some of the solutions we have, and the implication is that the most effective one is to get involved politically. Because it is. That’s the solution to the community action; to involve the community in solving the problem.

My perspective

All of this has been from my individual perspective. I’m a straight white dude in my thirties. I look, and probably outwardly project, a more traditional set of values than I actually hold. That affords me a whole lot of privilege in certain situations. Particularly in conservative areas there’s a baseline respect that comes with students having to call you ‘Sir’, ‘Doctor’, or ‘Professor’. It works, I think, really well to act as a Trojan horse for these students as someone who is not immediately bothered within their views. I’m a person who presents as fairly stereotypical American male, so there aren’t quick barriers thrown up that my views are from someone with a more liberal set of values, similar to how when the words “climate change” are used, conservative individuals ignore the rest of the argument made.

So your mileage may vary. This advice may not work, some might actually be horribly counter productive for somebody who doesn’t have a similar background or the assumed respect that goes with being a white, male professor. I chose to keep my preferred pronouns out of my email signature while at SHSU, because that’s a clear sign I’m a lefty. Part of my privilege is that it’s not a life-and-death or job-or-no-job situation for me to fight for those rights. I don’t have the level of righteous anger of someone marginalized, targeted, or worse by our government, which allows me the privilege to not having to worry about getting into many possible unsafe situations. I opted to not engage on some issues in my first semester teaching, and to only deal with very specific battles. Making sure that I taught my course material, including those viewed as political, as effectively as possible seemed like a good first step.

——————————-

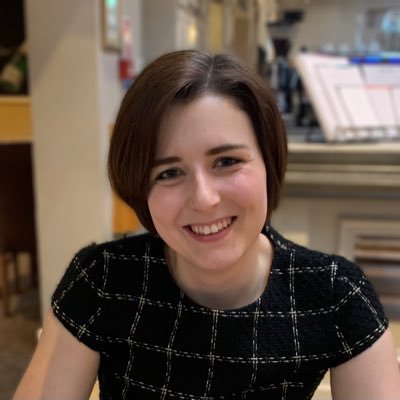

This blog is written by Cabot Institute member Dr Andy Fraass from the University of Bristol School of Earth Sciences. This blog has been reposted with kind permission from the Time Scavengers blog.