Rijasolo/AFP via Getty Images

Global climate change doesn’t only cause the melting of polar ice caps, rising sea levels and extreme weather events. It also has a direct effect on many tropical habitats and the animals and plants that inhabit them. As fossil fuel emissions continue to drive climate change, large areas of land are forecast to become much hotter and drier by the end of this century.

Many ecosystems, including tropical forests, wetlands, swamps and mangroves, will be unable to cope with these extreme climatic conditions. It is highly likely that the extent and condition of these ecosystems will decline. They will become more like deserts and savanna.

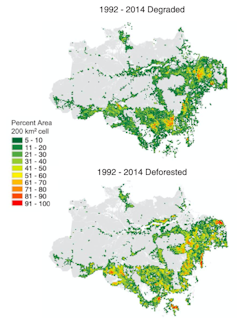

The island nation of Madagascar is of particular concern when it comes to climate change. Of Madagascar’s animal species, 85% cannot be found elsewhere on Earth. Of its plant species, 82% are unique to the island. Although a global biodiversity hotspot, Madagascar has experienced the highest rates of deforestation anywhere in the world. Over 80% of its original forest cover has already been cleared by humans.

This has resulted in large population declines in many species. For example, many species of lemurs (Madagascar’s flagship group of animals) have undergone rapid population decline, and over 95% of lemur species are now classified as threatened on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

Drier conditions brought about by climate change have already resulted in widespread bush fires throughout Madagascar. Drought and famine are increasingly severe for the people living in the far south and south-western regions of the island.

Madagascar’s future will likely depend profoundly on how swiftly and comprehensively humans deal with the current climate crisis.

What we found

Our study investigated how future climate change is likely to affect four of Madagascar’s key forest habitat types. These four forest types are the dry deciduous forests of the west, humid evergreen forests of the east, spiny bush forests of the arid south, and transitional forests of the north-west corner of the island.

Using computer-based modelling, we simulated how each forest type would respond to climate change from the current period up to the year 2080. The model used the known distribution of each forest type, and current and future climatic data.

We did this under two different conditions: a mitigation scenario, assuming human reliance on greenhouse gas reduces according to climate commitments already made; and an unmitigated scenario, assuming greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase at their current rate.

Our results suggest that unmitigated climate change will result in declines of Madagascar’s forests. The area of land covered by humid forest, the most extensive of the four forest types, is predicted to decrease by about 5.66%. Dry forest and spiny bush are also predicted to decline in response to unmitigated climate change. Transitional forest may actually increase by as much as 5.24%, but this gain will almost certainly come at the expense of other forest types.

We expected our model to show that mitigating climate change would result in net forest gain. Surprisingly, our results suggest entirely the opposite. Forest occurrence will decrease by up to 5.84%, even with efforts to mitigate climate change. This is because global temperatures are forecast to increase under both mitigated and unmitigated scenarios.

These predicted declines are in addition to the huge losses of forest already caused by ongoing deforestation throughout the island.

It looks as if the damage has already been done.

Climate change, a major threat

The results of our research highlight that climate change is indeed a major threat to Madagascar’s forests and likely other ecosystems worldwide. These findings are deeply concerning for the survival of Madagascar’s animals and plants, many of which depend entirely on forest habitat.

Not only will climate change decrease the size of existing forests, changes in temperature and rainfall will also affect the amount of fruit that trees produce.

Rijasolo/AFP

Many of Madagascar’s animals, such as its lemurs, rely heavily on fruit for food. Changes in fruit availability will have serious impact on the health, reproductive success and population growth of these animals. Some animals may be able to adapt to changes in climate and habitat, but others are very sensitive to such changes. They are unlikely to survive in a hot, arid environment.

This will also have serious knock-on effects for human populations that depend on forests and animals for eco-tourism income. Approximately 75% of Madagascar’s population depends on the forest and subsistence farming for survival, and the tourism sector contributes over US$600 million towards the island’s economy annually.

To ensure that Madagascar’s forests survive, immediate action is needed to end deforestation, protect the remaining patches of forest, replant and restore forests, and mitigate global carbon emissions. Otherwise these remarkable forests will eventually disappear, along with all the animals and plants that depend on them.![]()

——————————

This blog is written by Daniel Hending, Postdoctoral Research Assistant Animal Vibration Lab, University of Oxford and Cabot Institute for the Environment member Marc Holderied, Professor in Sensory Biology, University of Bristol. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Marc Holderied |