Our University is justly famous for the breadth and depth of its work on Sustainability. This ranges from research on the effect of micro plastics on the oceans, through food and farming, to the effect of resource-driven migration. We are also tackling arguably the biggest problem of all: developing the tools and techniques that will help us to fight climate change.

Our Sustainability Policy is clear that we need to walk the talk and demonstrate that we are supporting a sustainable world in our operations and strategies.

The University of Bristol’s Sustainability team co-ordinates sustainability activity across the organisation, continually innovating to find ways of reducing our environmental impact against a backdrop of growing staff and student numbers, increasingly bespoke teaching and ever more complex research requirements. The team has particular responsibility for waste resource management, energy, water and transport, and engages with staff and students in many different ways through community engagement, biodiversity activities, sustainable food and sustainable procurement.

1. A changing landscape

The team is led by Martin Wiles, who has been with the University since 2001. “Innovation is at the heart of what we do,” says Martin. “Everyone in the sector knows that the fundamentals are changing, and that change is accelerating. It’s difficult to see what the pedagogical, economic or political landscape is going to be even a year ahead. So, we see our activities as being guided by three principles: how do we support excellence in teaching, research and the staff and student experience? How do we reduce resource use whilst saving money? How do we ensure that we are compliant with increasingly complex environmental legislation? We also feel that we have a role in distilling our findings and disseminating good practice to the wider sector.”

2. Sustainable Laboratories

A good example of how this thinking is applied in practice is the Sustainable Labs Initiative, which focuses on improving the safety, sustainability and success of our laboratories. Energy manager Chris Jones says, “We had known for a long time that our highly-serviced labs represent only 5% of our floor area but use 40% of our energy. In recent years, controls for air handling have improved immensely and we have started to roll out best practice, starting with our Synthetic Chemistry building. We have been able to reduce electricity consumption by 30% there whilst still delivering the same level of service.” The project has been implemented by Chris, working with Anna Lewis, the Team’s Sustainable Labs officer. A former Research Technician herself, Anna works closely with academic and research staff to minimise resource use by better management. “Staff understand the issues,” says Anna, “and they are very happy to help. We can usually achieve better environmental performance and better safety through relatively small changes to our way of working.”

3. Closing the loop on waste

This sentiment is echoed by Rose Rooney, the Environmental Management System (EMS) and Circular Economy Manager. “If we treat everything in isolation, the task of compliance becomes unnecessarily expensive and intrusive in people’s work. Adhering to the EMS processes saves time and aids compliance. A good example is waste. If we are informed early and fully that a consignment of waste needs to be removed, we can deal with it cheaply and easily, often finding a route for it to be reused or recycled. We are moving away from the idea of waste to becoming a circular economy, where the output from one process becomes the input for another.” She cites the University’s popular and successful Re-store programme, which allows furniture and equipment from one group to be used by another, and The Bristol Big Give, where students’ unwanted items that would normally go to waste at the end of term are collected and sent to be sold for charities. Many tonnes of items are now being reused that might otherwise have gone to landfill.

4. Be The Change

Bristol Big Give is just one example of a number of behaviour change initiatives delivered by the team to encourage the sustainable behaviours as part of work, study and home life. Maev Moran, Communications and Campaigns Assistant, oversees the delivery of these initiatives: “We have found that audiences respond more positively and proactively to messages of empowerment than to negative messages. Be The Change, a scheme we launched in June, has quickly become the most popular ongoing initiative among University staff. It covers all areas of sustainability while making rewarding everyday actions, creating a step-by-step guide towards reducing our environmental impact both at home and in the workplace. The breadth of the scheme also means we can factor wellbeing in to our ability to have a positive impact, particularly as part of a wider community.”

5. Travel and transport

Amy Heritage is responsible for Transport at the University, including managing the University’s travel plan, facilities for people who walk or cycle to work or study, the University’s bus services (Bristol Unibus), including the new U2 bus service to Langford and initiatives/incentives to encourage behaviour change on all other modes of travel. “Our Staff and students are great at making sustainable travel choices. Our job is to make this as easy as possible.” She says that our travel plan is a key part in ensuring we are acknowledged as a good corporate citizen, and her team is looking at ways of improving the management of University vehicles and making it more attractive to replace meetings that would otherwise have required flights with video conferences.

Future plans

The team are starting the new academic year with plans for plans for efficiency savings on heating, laboratory ventilation and lighting, making sure we are compliant with new legislation, and collaborative work with Computer Science staff on how the operation of building services translates to staff and student wellbeing. There are plans for more renewable energy generation, smart controls for buildings, and adding to our electric vehicle fleet. “Once more, it’s a project about reducing our environmental impact while freeing up resources for excellent teaching and research, and staff and student wellbeing,” says Martin Wiles, “and that’s what we’re here to do.”

—————————–

This blog is written by John Brenton, Sustainability Manager in the University of Bristol’s Sustainability Team.

Read other blogs in this Green Great Britain Week series:

1. Just the tip of the iceberg: Climate research at the Bristol Glaciology Centre

2. Monitoring greenhouse gas emissions: Now more important than ever?

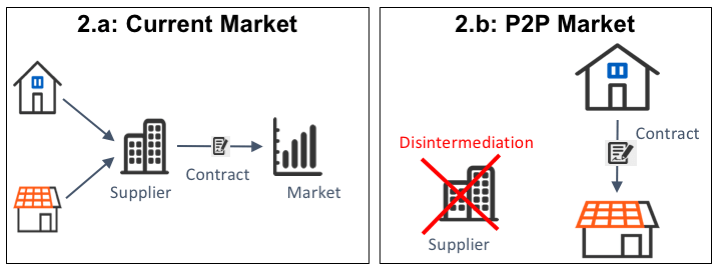

3. Digital future of renewable energy

4. The new carbon economy – transforming waste into a resource

5. Systems thinking: 5 ways to be a more sustainable university

6. Local students + local communities = action on the local environment