Few locations in London are more appropriate to discuss risk and extremes than the Shard in London. The daring skyscraper, completed in 2012, was among the first high-rise buildings to be designed in the aftermath of 9/11 – terrorism risk mitigation has been a major challenge for the structural engineers working on the project.

|

| The Shard, London |

On the 8 April 2016, the Mathematics Institute of the University of Warwick, in partnership with the London Mathematical Laboratory and the Institute of Physics, held the Real World Risks and Extremes meeting at the WBS campus at the Shard.

The invited speakers included Dr Gordon Woo (Risk Management Solutions), Professor Willy Aspinall (University of Bristol Cabot Institute and Aspinall & Associates), Professor Jean-Philippe Bouchaud (École Polytechnique and Capital Fund Management) and Professor Giulia Iori (City University London), as well as the writer Mark Buchanan (author and columnist for Nature and Bloomberg), who chaired the final panel discussion. The objective of the meeting was to foster interdisciplinary discussion on the methodology of extreme risk assessment and management, and this common theme was tackled in the talks from very different angles.

|

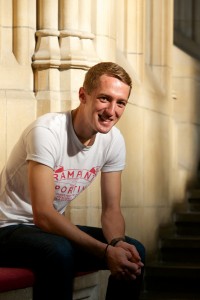

| From the left: Professor Aspinall, Dr Woo, Professor Bouchaud and Professor Iori. |

The day started with a thought-provoking speech by Dr Woo, who called for a new approach in the treatment of historical extreme events: rather than treating them as the only source of data, we ought to be performing some counterfactual analysis as well. Besides what we have experienced, what could have happened? Asking these type of questions, according to Dr Woo, would improve the robustness of risk assessments, after all, what happened was just one of many possible outcomes. Thinking about what could have been would help us to better prepare for the future.

Professor Aspinall followed with a talk about the use of expert judgement to quantify the uncertainty in mathematical models of natural processes. This is especially important when policy decisions are being taken based on these models, as in the case of climate change. The methodology was used to evaluate the uncertainty in the correlations between the different drivers of sea-level rise, discovering that its extreme values could be higher than previously predicted.

The talks by Professor Bouchaud and Professor Iori focused on the use of statistical mechanics-based and agent-based models to understand complex systems such as economics at a country scale or the global banking system. In particular, they both focused on the possibility of identifying the set of variables which govern crises in these systems. This is especially important for high-dimensional systems, as while there are many variables at play, generally only few of them can shift the system state from stable to unstable.

“Our main objective for the meeting was to stimulate cross-disciplinary discussion about how to improve uncertainty assessments of risks to society, especially given complex interactions and correlations among the many components of a natural or socio-economic system. The speakers represented such different fields of the risk sciences and industries, and yet their common ground became very clear during the panel discussion chaired by Mark Buchanan: don’t place your trust blindly in quantitative models or in past observations – use expert judgement of what might happen, supported by insights from qualitative models of complex systems and an analysis of near-misses. For most scientists, including myself, that are engaged in quantitative modelling of past and future observations, this consensus was an important lesson in how our science should contribute to policy and decision making.”