Piyaset/Shutterstock

In 2009, statistician Paul Murtaugh and climate scientist Michael Schlax calculated that having just one child in a high-emitting country such as the United States will add around 10,000 tonnes of CO₂ to the atmosphere. That’s five times the emissions an average parent produces in their entire lifetime.

The reason this number is so large is because offspring are likely to have children themselves, perpetuating emissions for many generations to come.

According to one prominent argument from 2002, we should think of procreation in analogy to overconsumption. Just like overconsumption, procreation is an act in which you knowingly bring about more carbon emissions than is ethical. If we condemn overconsumption, then we should be consistent and raise an eyebrow at procreation too.

Given the potential climate impact of having even a single child, some ethicists argue that there are ethical boundaries on how big our families should be. Typically, they propose that we ought to have no more than two children per couple, or perhaps no more than one. Others have even argued that, in the current circumstances, it may be best not to have any children at all.

These ideas have gained traction through the efforts of activist groups such as the BirthStrike movement and UK charity Population Matters.

Climate ethicists broadly agree that the climate crisis is unprecedented and requires us to rethink what can be ethically demanded of individuals. But proposing ethical limits on family size has struck many as unpalatable due to a number of concerns.

Liderina/Shutterstock

1. Blaming certain groups

Philosopher Quill Kukla has warned of the danger of stigmatisation. Affirming a duty to have fewer children might suggest that certain groups, which have or are perceived to have more children than average, are to blame for climate change. These groups tend to be ethnic minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged people.

Kukla has also expressed concern that if we start talking about limiting how many kids we have, the burden might end falling disproportionately on women’s shoulders. Women are already pressured to live up to society’s idea of how many children they should or shouldn’t have.

These worries do not directly concern what actual moral obligations to reduce emissions we have. However, they do highlight the fraught nature of talking about ethical limits to procreation.

2. Who’s really responsible?

A philosophical worry we’ve raised in the past challenges the conception of responsibility that underlies arguments for limits to procreation. We usually only think that people are responsible for what they do themselves, and not what others do, including their adult children.

From this perspective, parents might have some responsibility for the emissions generated by their underage children. It’s conceivable that they might also bear some responsibility for the emissions their adult children cannot avoid. But they’re not responsible for their children’s luxury emissions, or for the emissions of their grandchildren and beyond.

When broken down like this, the carbon footprint of having a child is much less drastic and no longer stands out compared to other consumption choices. According to one estimate that follows this logic, each parent bears responsibility for about 45 tonnes of additional CO₂ emissions. This is the same as taking one transatlantic return flight every four years of one’s lifetime.

Plane Photography/Shutterstock

3. Simply too slow

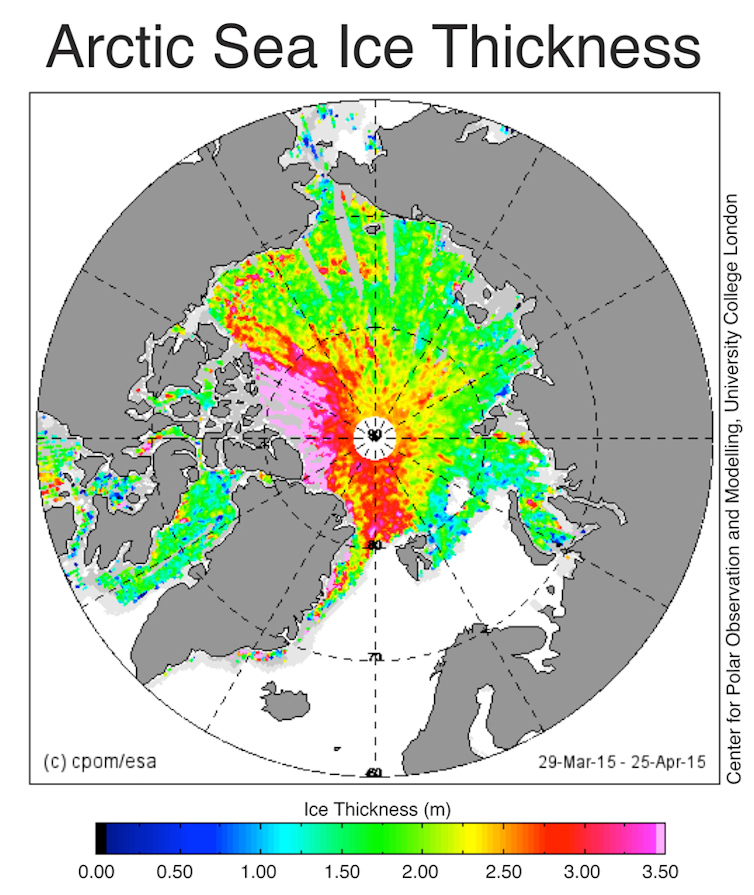

We are already seeing signs of climate breakdown. The ice is melting, oceans are warming and many climate records have tumbled already this summer.

To avoid the escalating impacts of climate change, climate scientists are in agreement that we must urgently reach net zero emissions. The most commonly proposed targets for this goal are by 2050 or 2070. In many countries, these targets have been written into law.

But, given the pressing need for urgent emissions reductions, limiting procreation is a woefully inadequate response. This is because the resulting emissions reductions will come into effect only over a much longer period. It is simply the wrong place to look for the emissions savings that we need to make now.

4. Path to net zero

Since limiting procreation does not reduce emissions quickly enough, per capita emissions need to drop – and fast. But that is not solely in the power of individual consumers or would-be parents.

What we are facing is a collective action problem. The ethical responsibility for reducing emissions rests on the shoulders of not just individuals, but also with societies, their institutions and businesses.

In fact, if we collectively manage to reduce our per capita emissions to net zero by 2050, then having a child today leads to only a small amount of emissions. After 2050, they and their descendants would cease to add to net emissions.

However, despite political commitments to achieve this target, the jury is still out on whether this target will be met. More than US$1.7 (£1.3) trillion is expected to be invested in clean energy technologies globally this year – by far the most ever spent on clean energy in a year. Yet, the UK continues to grapple with how to fund its net zero transition – a predicament they’re unlikely to be alone in.

Philosophical arguments that we should have fewer children challenge our understanding of what morality can demand in an age of climate change. They also call into question whether the most meaningful choices we can make as individuals are simple consumption choices (for example, between meat and plant-based alternatives). But the philosophical debate about whether there is a duty to have fewer children is complex – and remains open.

——————————

This blog is written by Dr Martin Sticker, Lecturer in Ethics, University of Bristol and Dr Felix Pinkert, Tenure-track Assistant Professor, Universität Wien. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.