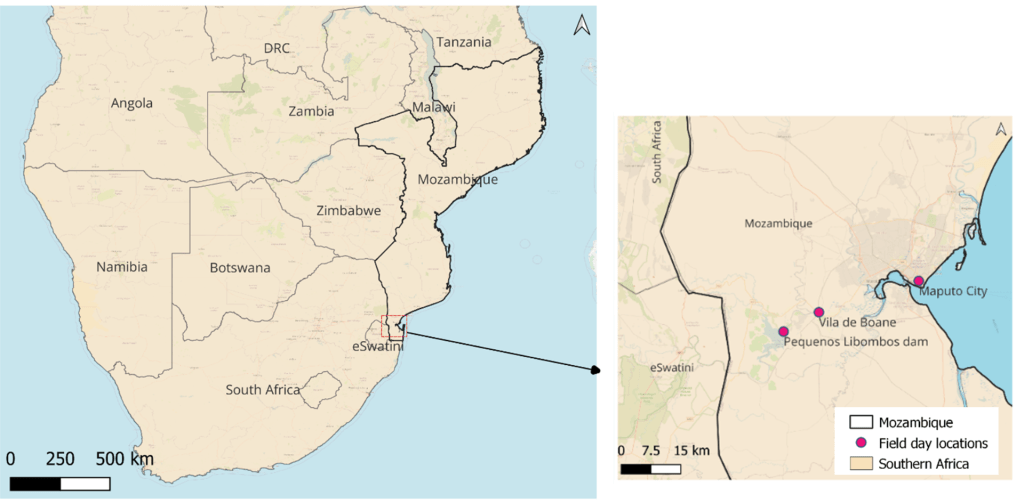

I’d never given a huge amount of thought of what a dam manager did until I visited Pequenos Libombos dam in Mozambique in October 2023. Standing at the dam, in hot conditions, listening to the lived experience of people who work on the ground and explain what they do during a tropical cyclone leaves you with more understanding than any peer reviewed journal article. Context is everything. It’s why visiting the countries I’m researching is something I do given the chance.

That’s what members of Bristol projects REPRESA (co-led by Prof Elizabeth Kendon at University of Bristol & UK Met Office, Dr Luis Artur from Eduardo Mondlane University and Prof Francois Engelbrecht from University of the Witwatersrand) and SALIENT (led by Dr Rachel James, University of Bristol) did in October. The REPRESA project aims to understand compound tropical cyclone risks, impacts of tropical cyclones and improve early warning systems in Mozambique, Malawi and Madagascar. Seeing the research alignment in projects, the SALIENT team also joined. The SALIENT project aims to improve the characterisation and communication of future climate information for national adaptation planning in southern Africa.

On the field trip day, we travelled to Pequenos Libombos dam and heard from a government official from the Vila De Boane Municipality. It was this day where I had my epiphany that if I ever left academia, dam management is not my calling. Providing water to the local population is the dams primary role and it provides 2 million people within Maputo Province with access to water. That is more than 4 times the population of Bristol.

The management of Pequenos Libombos dam is difficult as there are many other people and industries to consider and keep safe and happy when making decisions. From the businesses who want to use the dam’s water for industrial purposes to the farming communities that are reliant on the water for irrigation, and hydroelectricity companies that want to use the dam to create energy to the communities downstream that may be flooded if the dam releases water too quickly. The dam catchment is also shared with 2 of Mozambique’s neighbouring countries; eSwatini and South Africa, adding another element of complexity to the dams management.

Management must carefully balance both periods of water surplus and deficit and Maputo has experienced numerous extreme weather events in recent years. The 2015-2016 southern African drought impacted Central and Southern Mozambique and more recently the remnants of tropical cyclones in 2019, 2011, 2022 and 2023. During February 2023, Tropical Cyclone (TC) Freddy passed over Madagascar and southern Mozambique before returning a couple of weeks later to central Mozambique. It is thought to be the longest lived and have the highest accumulated cyclone energy of any cyclone on record, awaiting formal investigation from the World Meteorological Organization. Although TC Freddy didn’t directly pass over Pequenos Limbombos, its associated rainfall resulted in 250 mm of rainfall at the dam in one day. For context, the Bristol experiences 265mm rainfall, on average, in October, November and December combined. To avoid a breach of the dam, discharge was released at the maximum rate, which is more than 500 time more than normal.

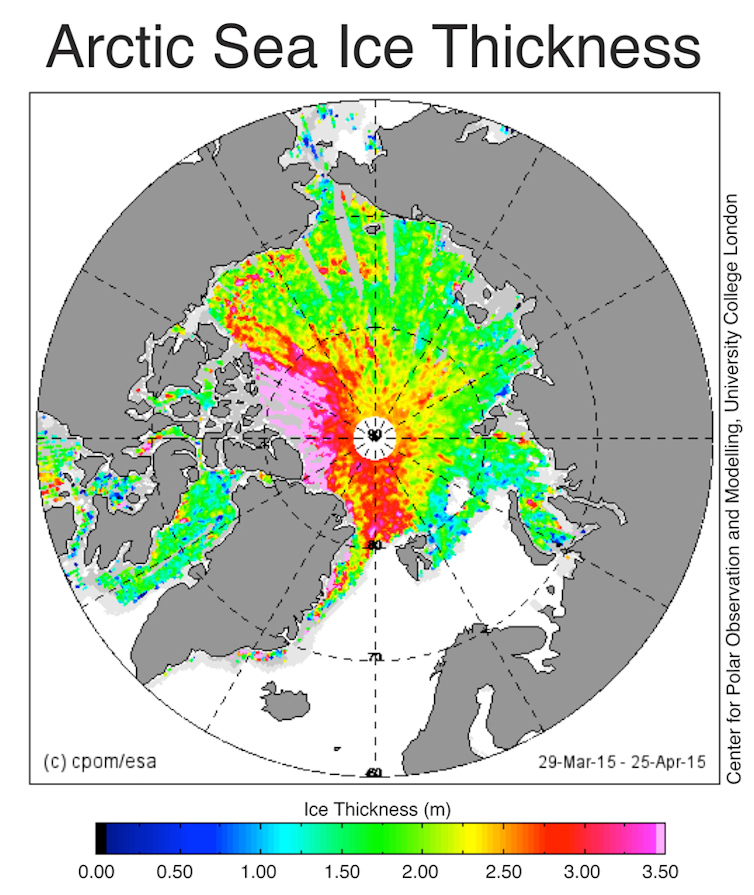

Globally there is evidence that TCs and their impacts are being impacted by climate change. The frequency, intensity and storm tracks of TCs may be changing meanwhile, rising sea levels may lead to higher storm surges. Yet we know a limited amount about how tropical cyclones may act in a future with increased global sea surface and air temperatures. TCs in the Indian Ocean are particularly under researched, but recent and frequent events have highlighted the importance of understanding TCs in a changing climate.

After hearing about the vast amount of rain that fell in February 2023, we walk past the disused hydroelectric generator that was forced to cease operation during the drought as it was no longer economically viable. It really hammered home the complexities faced when trying to manage such a huge piece of infrastructure during extreme events. Similarly, it is clear why research projects like REPRESA and SALIENT are needed to understand how tropical cyclones may behave in the future and explore how early warning systems and climate change adaptation can be strengthened.

The human side of extreme weather

After the talk at Pequenos Libombos Dam, we visited the Municipality of Vila de Boane. Vila de Boane is located roughly 15 km downstream from the dam and the River Umbuluzi passes through the municipality. The municipality experienced large scale flooding after the dam was forced to increase to maximum discharge during the February 2023 rainfall.

Despite already hearing about TC’s Freddy’s impacts at the dam, they were not as focused on the human impact. The leader of the municipality compellingly described how 16,000 people were impacted overnight, 6000 people were displaced and 6 people sadly died. The community water pump was destroyed, leaving people without water for 3 months. The municipality leader said he had never seen that amount of water passing through the municipality at such high speed before. Meanwhile, money that had been budgeted for development initiatives, had to be redirected to repair and response. It was not clear if extra money had been sourced for the development initiatives.

It was also highlighted that the increased release of water from the dam occurred over night with little warning. The municipality had been told to expect “above normal” rainfall and to avoid being close to rivers and move farming machinery further inland. But as the municipality leader questioned, what does “above normal” actually mean? People will perceive this message differently, which will influence how they act upon it. As part of the SALIENT research project, I am researching how we best communicate future climate information to decision makers and this anecdote will stay with me. It’s clear that improved communications are needed in both weather and climate services, something REPRESA is also aiming to research further.

Reflections and collaboration

After hearing about the vast amount of impacts the flooding had on Villa de Boane, we waited for our transport back to Maputo under the shade as it was too hot to stand in the sun. It was clear everyone from the REPRESA and SALIENT teams, both physical scientists and social scientists, had taken a lot from the field day. There was discussion about what the research should consider as well as the different angles that could be taken. It also fostered collaboration, SALIENT team member, Alan-Kennedy Asser, is providing the REPRESA team with analysis of precipitation trends from a multiple ensembles of climate models to characterise the range in future projections over the region. Meanwhile I spoke with some REPRESA team members in more depth about future climate information and will be providing risk communication training session in the future.

My personal key take away is that understanding the context and hearing the lived experiences of people working and living with extreme weather events enriches me as a researcher. Similarly, collaborating with researchers and practitioners on different projects enhances your work by providing questions and inputs from different standpoints. And finally, I’m too indecisive a person to ever be a good dam manager.

——————————————

This blog is written by Cabot Institute for the Environment member, Dr Ailish Craig, School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol with contributions from Dr Alan Kennedy-Asser, School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol and Dr Rachel James, School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol.

In an ever-evolving world, societal dynamics are continually shifting, reflecting the multifaceted nature of the human experience. One of the most profound changes we have witnessed in recent decades is the transformation of family structures, with divorce becoming a common facet of modern life

In an ever-evolving world, societal dynamics are continually shifting, reflecting the multifaceted nature of the human experience. One of the most profound changes we have witnessed in recent decades is the transformation of family structures, with divorce becoming a common facet of modern life