This blog is part of a series from the Cabot Institute for the Environment on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s recent AR6 report (IPCC, AR6), with this post covering the output of Working Group 1 and the physical scientific basis of climate change. This article also features a chat with Professor Dan Lunt, a Climate Scientist at the University of Bristol who focusses on paleoclimates and climate modelling, and a Lead Author on the IPCC’s AR6 report. For links to the rest of the series, see the bottom of the post.

The IPCC begins their 6th Assessment Report by explaining the physical science basis and publishing the finding of Working Group 1 (WG1) in August 2021. This means that, rather than considering the impact on humans, ecosystems and societies covered by later working groups, this report only looks at the effects on the planet from a physical standpoint. Consider this part of the report to be describing the problem, where later reports describe the impacts and then the possible solutions.

Here are the key points from WG1, detailing the physical science basis:

Human activity has unequivocally caused a change in the global climate.

If you were in any doubt before, let this be the sole key message you take away from this report.

Human activity has caused widespread warming of the land, ocean an atmosphere, affecting weather systems, ecosystems, and the cryosphere (areas covered by ice such as mountain glaciers and the polar regions).

One of the main drivers of this change has been Greenhouse Gases (GHGs), which have been observed to be increasing in atmospheric concentration since as far back as 1750 and the beginning. These gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), come from human processes that burn fossil fuels – transport, energy production, intense cattle farming for example.

Greenhouse gases in the atmosphere act like blanket, trapping rather than heart from the sun, warming the Earth. We also know from studying past climates that the Earth will get warmer with greater atmospheric CO2 levels.

Changes to the climate are happening at an unprecedented rate.

|

| Figure 1: Graph from AR6-WG1 showing the unprecedented levels of warming seen in the last 2000 years. |

You may have heard that the Earth’s climate has naturally ebbed between periods of hot and cold. This is completely true, however it can be a misleading statement that completely undersells the issue. Human activity has caused the planet to warm at an unprecedented rate. We are currently undergoing thousands of years of warming in just a few decades (fig.1) – much to fast for adaptation from the world’s ecosystems.

As such, the Earth will take millions of years to recover and reach an equilibrium. I highly encourage you to check out climatearchive.org’s simulations of the next million years using cutting edge modelling data – created by the Cabot Institute for the Environment’s Sebastian Steinig.

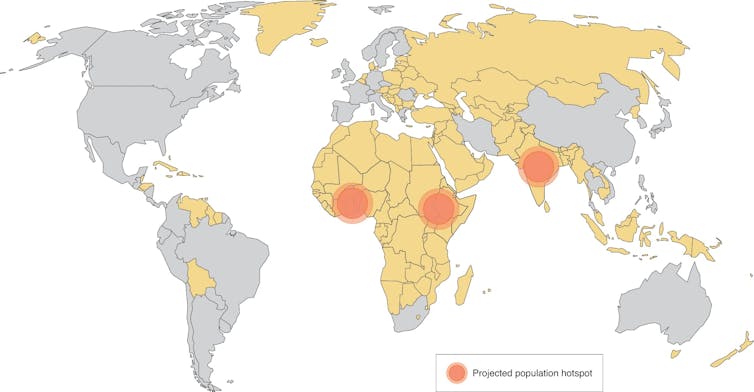

Climate change is ALREADY affecting every inhabited region on Earth, with observed increases in extreme weather and climate extremes.

Many people believe that the climate crisis is far off in the future, a problem to prevent before it arrives. However, this is not the case. It’s already happening under our noses. And everywhere. Every inhabited region in the world currently experiences an increased likelihood of an extreme weather event, extreme heat drought, or extreme precipitation. This summer for example, temperatures in the UK have been modelled and subsequently measured to creep above 40°C, unprecedented for a region with a usually temperate climate and setting national records.

Increased warming leads to an increase in effect and creeps towards a tipping point from which recovery is impossible.

You might have heard phrases like “2 degree C future” or “1.5 degree C rise” in the news, but what do these really mean? These numbers refer to the global mean temperature rise using a rolling average of the previous 20 years, relative to the temperature measured between 1850-1900 when climate change started to begin. Currently, the average global temperature anomaly sits above 1 degree C of warming (fig.1).

The Earth system is remarkably robust, but not quite robust enough to maintain an equilibrium with such rapid warming in a short space of time. One place where this is most stark is the cryosphere – parts of the Earth usually covered by ice all year round (glaciers, polar regions for example).

Melting has already begun and will continue to happen for decades even if emissions magically ended tomorrow. This is incredibly troubling, since the cryosphere also happens to be huge carbon store in the form of methane trapped in the ice. This creates what’s known as a feedback loop, where the effects of warming lead to greater warming in themselves.

Through studying paleoclimates, the IPCC reports that climate sensitivity and therefore “tipping point” sits at around 3 degree C, resulting in total climate breakdown.

Significant and immediate action limiting Greenhouse Gas emissions will be a major key in fighting climate change.

The one silver lining the report alludes to is that IPCC scientists are confident that the climate crisis is caused primarily by greenhouse gas concentrations, therefore we know the solution – reducing emissions quickly and effectively will mitigate against the worst warming in a big way. Pursuing a net-zero CO2 strategy and limiting other GHG emissions will be absolutely necessary. Working Group 3’s report on the Mitigation of Climate Change goes into greater detail on how governments can work together to go about this. This will be published on 29 August 2022.

Insight from IPCC WG1 author Professor Dan Lunt

Professor Dan Lunt is a Professor of Climate Science, Cabot Institute member and a key author on the IPCC’s WGI report.

How did you get involved with IPCC AR6?

|

| Dan Lunt |

“I was involved with the previous IPCC report, AR5, providing some data and graphs for a section on polar amplification in past and future climates (the disproportionate warming of the polar regions relative to the rest of the Earth system). This time round, a call went out around four or five years ago for authors to work on the upcoming Sixth Assessment Report. I applied for and was chosen to be a Lead Author on Chapter 7 of the AR6 report – a section focussed the Earth’s radiation budget and Climate Sensitivity, as well as on paleoclimates as evidence for the patterns of global warming, such as polar amplification.”

What’s one key point you’d like to get across from the work of Working Group 1?

“For me, what I would interpret as the key message would be climate change is already happening, and it’s happening all over the globe. It’s unprecedented in terms of its magnitude and its speed of change, relative to the past tens of thousands of years. It’s unequivocally caused by human activity.”

“One of the new key points in this assessment report is that there’s a lot more evidence now that there are changes in the frequency of extreme events. We now have enough data to say that this increased frequency is human induced. So that’s more droughts, floods, extreme heat events etc.”

———————————–

We recommend taking a look at the IPCC’s full reports and report summaries for yourself if you seek to further understand the evidence and reasoning behind their headline statements.

As we’ve discussed the scientific basis for climate change, you may be wondering what the real-world impacts. The specific impacts on ecosystems, global health and on human society will be covered in greater detail in our summary of WG2’s report titled “Impacts, Adaption and Vulnerability”, publishing tomorrow (Thursday, 28th of August).

This blog was written by Cabot Communications Assistant Andy Lyford, an MScR Student studying Paleoclimates and Climate modelling on the Cabot Institute Master’s by Research in Global Environmental Challenges at the University of Bristol.

|

| Andy Lyford |