We interview the four academic experts who will be attending COP30 in Belem, Brazil, from the University of Bristol’s Cabot Institute for the Environment. We ask them what their main focus will be at the COP and what they’re most looking forward to, from running a side event with indigenous partners, to providing free legal advice to developing country delegations…

Dr Karen Tucker (School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies)

What is your area of research?

I research the ways in which Indigenous peoples and their knowledges are included (or not) in environmental policies and related programmes. A particular focus, at the moment, is the ways in which climate mitigation policies impact on Indigenous peoples, and the ways they can better support Indigenous knowledges, economies and rights.

What will be your main focus at COP30?

I will be presenting some work I’ve been developing with Indigenous Mapuche Pehuenche partners and Chilean forest scientists at an official UNFCCC side event. I co-organised the event with my colleague in SPAIS, Katharina Richter, and Indigenous and NGO partners in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru and the UK. As well as this, I plan to attend events on Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous leadership in climate governance, and on the connections between forests, biodiversity and climate governance.

What is the main reason you are attending COP? What are you looking forward to?

As well as an opportunity to learn about and contribute to discussions on climate policy as it relates to my specific areas of expertise, attending COP30 will hopefully allow me to continue developing conversations with partners and potential audiences for my research. This is my second COP, and I’m excited to see how policymakers respond to the symbolism and experience of attending a climate conference in the Amazon!

Karen will be running a side event Carbon markets, forests and Indigenous alternatives in the Blue Zone of COP30 on 13 November 2025. Find out more about the event.

Dr Alice Venn (School of Law)

What is your area of research?

I research legal responses to the climate crisis and I’m interested in how the UN climate regime can respond better to the needs of countries and communities on the frontlines of climate change. I explore human rights and climate justice in this process, thinking about how the decisions taken can be made fairer and more representative of those who are most severely impacted.

What will be your main focus at COP30?

I will be working as a liaison officer with the charity, Legal Response International, who provide free legal advice to developing country delegations and civil society groups participating in the climate negotiations. Their work aims to address the inequality between different countries’ negotiating teams, bolstering the legal capacity of countries facing the most severe climate impacts. For me, this will involve meeting with delegates and assisting the team in researching and drafting advice for the requests that come in.

I will also be following the loss and damage and just transition negotiation streams closely as my research centres around these topics. I’ll then share notes and updates with the charity team to draft a summary of the COP outcomes.

What is the main reason you are attending COP? What are you looking forward to?

I’m really looking forward to attending COP30 as although I’ve been researching international climate law for over a decade now, this will be the first time that I’ve attended a COP in person. Working with LRI offers a fantastic opportunity to put my research expertise into practice in an impactful way. I’m also excited to see how the recent International Court of Justice opinion on climate change will influence the discussions.

Dr Filipe Machado França (School of Biological Sciences)

What is your area of research?

Our research area is ecology and environmental sciences. We study insects (dung beetles, butterflies, moths, and bees) to measure nature health in tropical forests. We also work in close collaboration with multiple stakeholders (e.g. policymakers, park managers, local and traditional communities) to co-develop research and guidelines for conservation strategies and environmental practices and policies.

What will be your main focus at COP30?

I would like to engage on activities and discussions / negotiations involving climate-biodiversity relationships, with a particular focus on National Adaptation Plans and Nationally Determined Contributions for countries of interest (e.g. Brazil, Ghana, Malaysia, and the UK).

What is the main reason you are attending COP? What are you looking forward to?

I have been to COP16 in Cali (November 2024), but only with access to the green zone. I contributed to a workshop, which was an excellent opportunity to build new relationships and understanding other initiatives integrating science to decision-making.

Watch Filipe talk more about his Cabot Institute funded research in Amazonia on YouTube.

Laurence Hawker (School of Geographical Sciences)

What is your area of research?

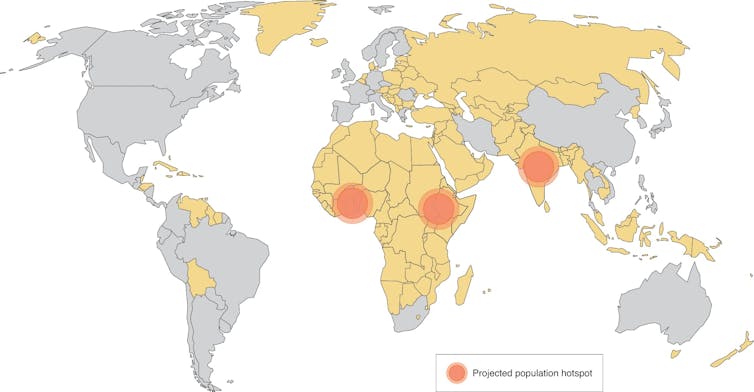

Making global scale maps of where people are most likely to live in the future (until 2100) for various future scenarios. I am also interested in researching risk of already displaced people from climate hazards.

What will be your main focus at COP30?

Networking with members of Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP), Integrated Impact Assessment Modeling Consortium (IAMC), IOM and UNHCR. I am also keen to meet with policy makers and hear about their concerns for the future and how future maps of population can be best utilised. I want to participate in events primarily on focussed on cities and displaced people. I am also fascinated to observe issue areas and negotiation streams, especially to learn how the future population maps could possibly help inform climate reparations / people at risk.

What is the main reason you are attending COP? What are you looking forward to?

Talking to people across academia, NGOs and governments so we can shape our future population maps to be most useful to the most people. As we are at the early stages of the project, it is so invaluable to get these insights. I am very thankful for this opportunity, especially for someone like me at the early stage of their career.

——————————-

COP30 is taking place between 10 and 21 November 2025.

- Find out more about the University of Bristol at COP30 on our website.

- Are you a journalist looking for media trained academic experts for COP30? We’ve got you covered.

- Attend our COP30 ‘Personal to the Planetary’ event series in Bristol.

——————————-

This post was created by Amanda Woodman-Hardy, Communications and Engagement Officer at the Cabot Institute for the Environment.

.jpg)